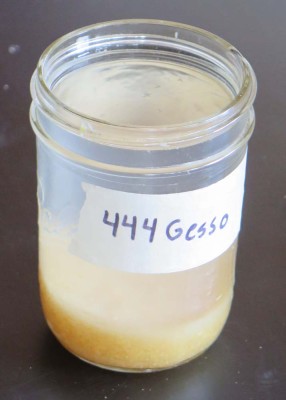

So there I was, mixing up a new batch of traditional gesso to use as the ground (primer) on some japanning samples I was preparing for an upcoming video shoot at Popular Woodworking. The first step is always the soaking of the glue in order to cook it twice before adding the calcium carbonate (a/k/a whiting or pulverized chalk) to the mix to create the ground.

I was using 444 gram weight strength (gws) glue for the mix because I could not put my hands on my jar of 512 gws granules. My working process has always been to put dry gue granules into the bottom of a jar filling approximately 1/10th of the height, then adding water to let it hydrate in preparation for the cooking. I usually let this sit overnight.

As always, within minutes the glue began to swell as it adsorbed water into the dry protein coils, and expand until it was fully hydrated after a few hours. This visual reminder in turn caused me to reflect on an important truth about hide glue and how we use it.

Now, the relative tensile strength of glue is a fairly linear function of its gram strength fraction, so logic would lead us to conclude that the highest number of glue fraction would yield the highest bond strength. (Tensile strength, the ability for a material to resist being pulled apart, and shear strength, the ability of a glue line to keep two adherends together while they are being puled apart parallel to the glue line, are fundamental factors in glue performance.)

Higher gram weight strength glues result in the best performance, right? After all they have the higher tensile and shear strength.

Not so fast!

The water uptake for total hydration is also a linear function and I could show you the data I derived in my testing, but my lab notebook for glues and their manipulation is somewhere in the remaining boxes of books awaiting unpacking. But the point is this: the higher the number of the glue grade/fraction, the more water is required for complete hydration. Coincidentally, my testing confirmed that the viscosity of all grades is the same at total hydration, but the amount of water uptake for total hydration can vary dramatically as the longer protein chains of the higher grades need a lot more water.

In other words a low number glue and a high number glue can have the same hydration ad viscosity despite the fact that the solids content percentage for the higher number is only a fraction of the solids content percentage of the lower grade.

What does this mean? Well, for on thing the higher glue grades require a lot more water to achieve the same working properties of the lower grades (there are many other considerations, but this is an important one). And, all the water that goes into the hide glue system has to come out in order for the glue to achieve its maximum performance.

Seriously, what does this mean?

What it means is that the “stronger” higher gram strength glue may not yield the strongest glue line. Since a higher glue grade has to take on more water to be used, it will in turn lose that water in curing, and that water loss is accompanied by shrinkage of the glue mass, or, more likely, the in-building of internal stresses (sometimes breathtakingly huge) into a glue line, setting the stage for glue line fracture and eventual failure in the future.

I used to use 315 gws glue a lot, sometimes even 379 gws. However after some simple testing my strategy has changed pretty dramatically such that I now use 192 gws glue (or even lower) for most of my routine joinery applications and leave the higher gram weight strength glue for other applications.

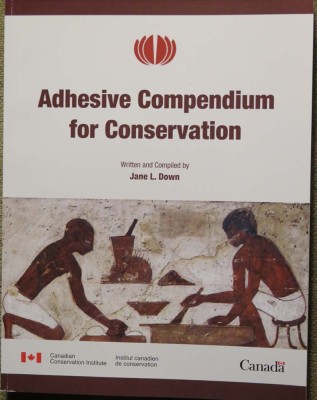

I got a package from FedEx today with an Ottawa, Ontario return address. Had I ordered something from Lee Valley and forgotten about it? That potential is not outside the realm of possibility.

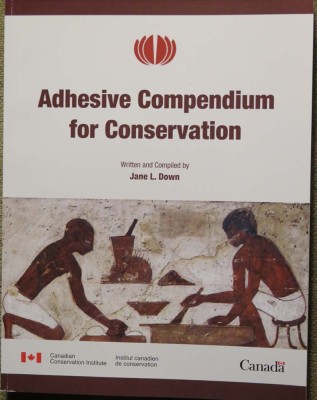

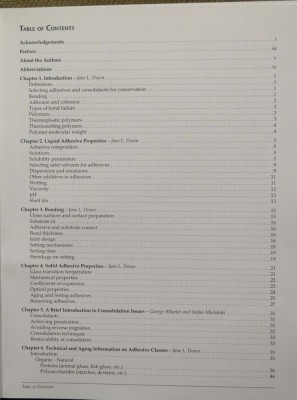

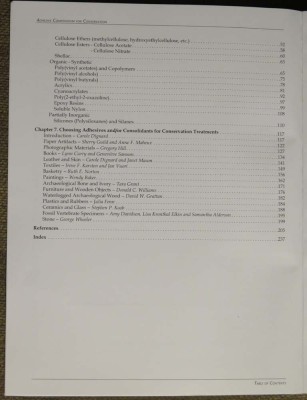

Instead of a hand tool, it was a brain tool. In fact, it was a really good book that had been in the works for a decade or longer. It was published by the Canadian Conservation Institute, a renowned research and preservation treatment entity within the Canadian government, and edited by my friend and colleague Jane Down (who may be the best adhesives researcher on planet). It will be a tremendously useful resource for anyone interested in the subject of adhesives and their use for a wider range of artifact types. I expect to use it with some regularity.

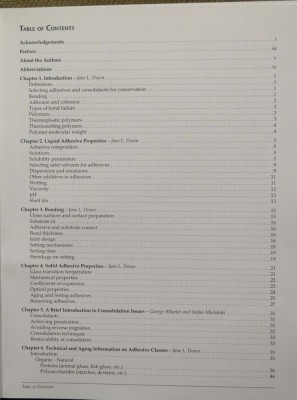

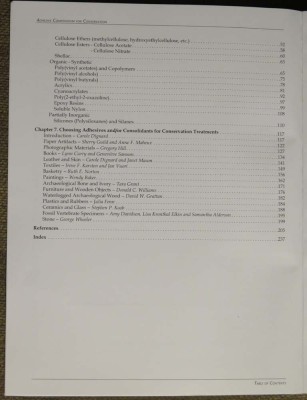

The Table of Contents reveals the breadth and depth of the concepts, materials and practices covered. Were I still interested in such things, being invited to contribute would be a very nice resume’ enhancer, but at this point in my life I am just trying to live out my friend Mike’s dream to “do interesting projects with good people in great places.” Of course, for me that “great place” is The Barn.

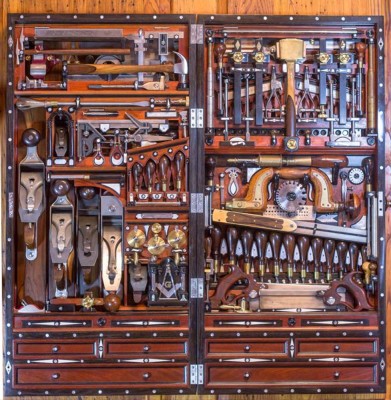

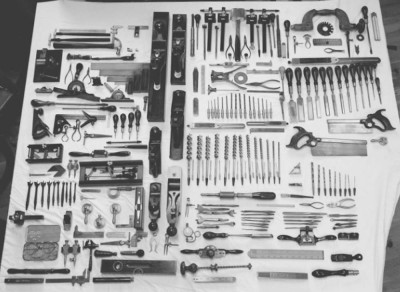

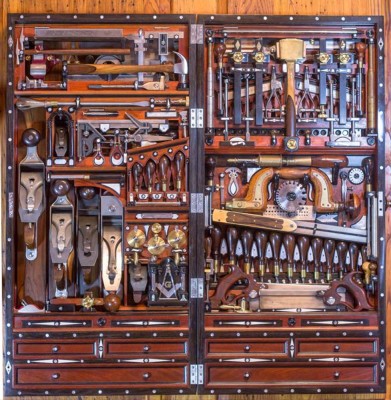

JimM has been doling out images to me in regular increments. He is perhaps just extending my time of admiration for his workmanship and vision in replicating the HO Studley Tool Cabinet.

With his permission I am sharing them with you.

We live in a generation that is seeing perhaps the most remarkable renaissance of woodworking in history. After decades of professional scholarship revolving around historical furniture-making technology, I think that we might be living at a time when more good furniture is being built than at any time in history. Much of this is production is driven by passion rather than commerce. I recall a presentation by Adam Cherubini some years ago when he posited that the future vitality of woodworking was in the hands of avocational craftsmen rather than vocational artisans. In this proposition I am in complete agreement.

Yes, vocational woodworking is flourishing in a manner I thought I would never see. But this pales in comparison to the tens and hundreds of thousands of enthusiasts who are, in particular, often pursuing historical hand tool skills, or like me adopting a hybrid approach of using hand tools and machine tools in concert to produce exceptional furniture. Precision joinery, exquisite wood selections, and generally orthodox forms are the hallmark of this new movement. And evangelists like Chris Schwarz, Paul Sellers, Mike Siemsen, and a multitude of others (especially in New England) are providing the cheerleading.

Further, there have been many modern explorers of the lines and forms of furniture, based on views to the past and into the future, including in recent generations folks like CR Mackintosh, Alvar Aalto, Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Gerrit Rietveld, Charles Eames, followed by a crew of our almost-contemporaries including James Krenov, Sam Maloof, and George Nakashima, who undoubtedly inspired many of you along with me as they attacked the boundaries of design. Our own contemporaries include luminaries like Peter Galbert, George Walker and Jeff Miller who are merging the past and future in teaching us to be better aesthetes in wood. The roster of crazy-good artisans currently working is astoundingly large, and I admire and respect them immensely.

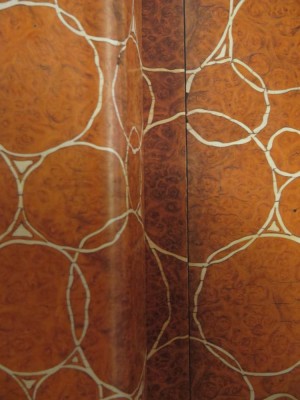

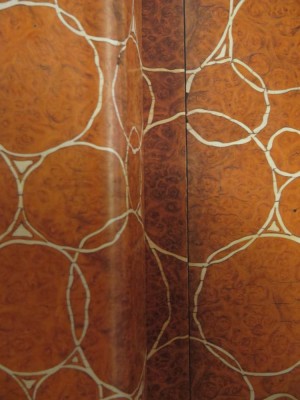

I am fully capable of executing competent joinery and employing superb woods (as I blogged earlier, 2016 will be the Year of Making for me), but in truth my furniture-craftsmanship affinities lay elsewhere. My own creative inclinations furniture-wise reside vaguely at the crossroads of Krenov and the Ming and Tokugawa Dynasties. Whether by native temperament, imprinting during my first real job in the furniture restoration trades (42 years ago this week), or simple curiosity (read: contrariness) I have long been intrigued by technological/craft/materials science innovation, but even more by the artistic expressions generally un-explored by most of our contemporaries: the decorative surface. I intend to expand my facility by continuing my trek down the road of surface decoration and exhort others to join me on the journey over the coming decades.

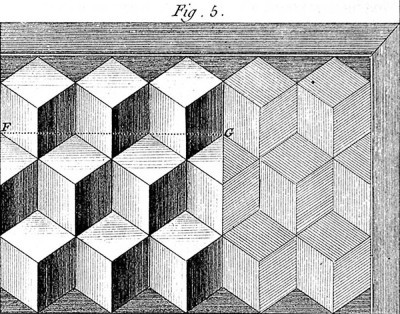

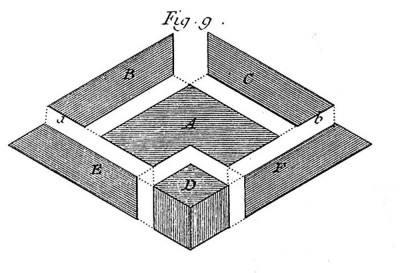

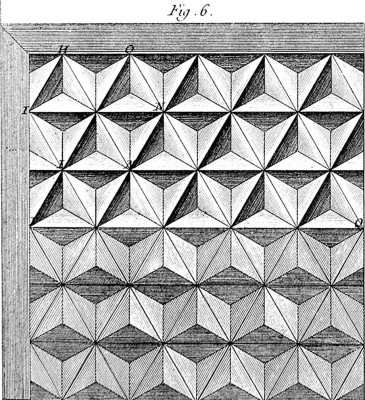

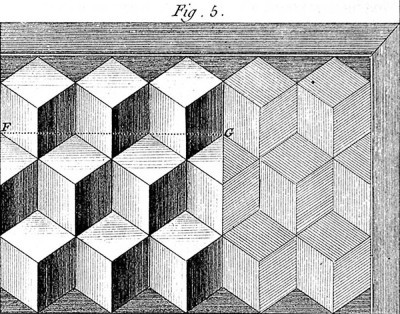

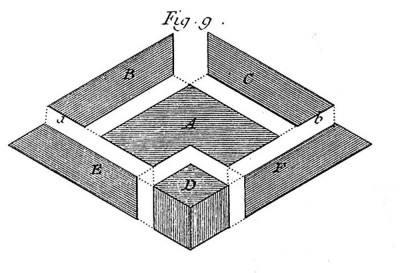

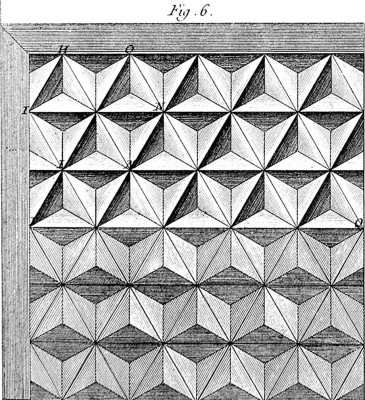

This journey will have two simultaneous paths. The first is marquetry, in particular, parquetry.

The appeal of exquisite marquetry representations in Andre Roubo’s L’Art du Menuisier eventually grew into our ongoing efforts to bring this monumental treatise to English language audiences. In an amusing ex poste exchange, Lost Art Press Publisher Chris Schwarz confided that I was presenting the Roubo volumes exactly backwards from the woodworking publishing perspective. By starting with the information that interested me the most — marquetry and finishing — I was standing the series on its head by bringing to press first the sections of least interest to my fellow woodworkers. So sue me.

My affection for 18th century French veneerwork artistry has been incorporated into my own craft vocabulary for almost thirty years now, itself sprouting from my exposure to dozens, maybe hundreds, of examples of the real thing in mansions of Palm Beach when I was just starting in the trade. Though comparatively dim at the moment, the torch of marquetry is still being carried by a few gifted men right now, including my long-time acquaintance Patrick Edwards (whom I have known since before he went to France the first time), Silas Kopf, whom I met only last year, Paul Schurch whose acquaintance I have yet to make, and Craig Vandall Stevens (ditto). What makes their artistry most interesting to me is that their artistic techniques differ from each other, and none of them do it the way I do.

Now that I have finished with Henry O. Studley and I am fully mobile I can hardly wait to expand my adventures in this decorative surface technique. Even by simply copying the Roubo syllabus faithfully the palette is nearly inexhaustible. And this is just the beginning as I have a lot of parquetry ideas awaiting birth. Think Galle meets Riesener with seasoning by Ruhlmann.

Next time: the second route to the ultimate decorative surfaces, which itself splits into three separate paths

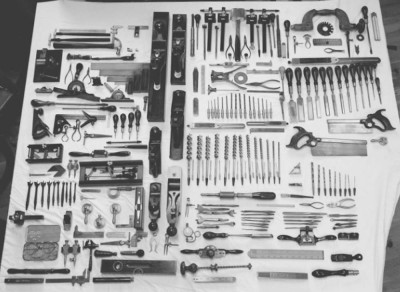

I have mentioned in the past that the quantity of hard facts we know about Henry O. Studley is so sparse that the only personality profile we have of him is his ensemble of the tool cabinet and accompanying workbench. Anything more is at this point speculation.

On the other hand I am acquainted with JimM a bit, I know we have met and chatted at an SAPFM meeting last summer when I was speaking about Studley and presenting a demonstration on replicating aged, historic surfaces. I’d heard through the grapevine that he was replicating the tool cabinet as precisely as possible, including the contents, and we corresponded a time or two about details of the cabinet.

And then he sends me the pictures posted inside this blog entry. Though I know the barest minimum of facts about JimM, I can see clearly from these images that this is a man who must not sleep much.

With this project JimM has set the bar very high for that multitude of you in the lignosphere who are equally captivated by the virtuosity of Henry O. Studley.

Well done, JimM! As the monomaniac who completed his homage to Studley the first, I will have to think of an appropriate prize for you.

Recent Comments