… for my FORP Roubo bench to find its rightful home underneath the bank of northeast-facing windows.

As I’ve mentioned previously the spatial arrangement in my studio has been undergoing reorganization, or as James “Stumpy Nubs” Hamilton calls it, “rearrangeritis.” In one sense I am living with the curse of too much space, thus I need not be particularly efficient with my shop layout nor unduly burdened by the necessity of tidiness. I am trying to improve on both counts.

After completing the construction and assembly of my 2013 FORP workbench last year I planted it on the north wall of the shop, thinking that would be a good place.

I was wrong. I back-filled the space around it with my favorite little two-sided workbench and some other stuff and before long the whole space was a chaotic mess.

Plus, that new space was so crowded it precluded me even installing the superb wooden screw leg vise that was part of the original design. In the original configuration the four inch round block plus the three inch moveable jaw would have made the whole thing stick out too far to even walk past easily. There simply was no room to use it even if it were installed so it remained on the sideline.

After much cogitation I decided to move it underneath the large bank of windows facing east. This was not done lightly — rasslin’ an 8-1/2-foot, almost 500 pound workbench by myself is not something to undertake on a whim. I set aside a day to move the bench and the other nine things that had to be moved first in order to accommodate the move around the corner, but it was absolutely worth it.

This should not have been a huge surprise to me as it was the location for my first Roubo workbench built from timbers left over from the barn re-erection. Truly, this was THE right location for the bench and I was an idiot for not recognizing this from the git-go.

I now have a sublime arrangement of my beloved first workbench sitting in the middle of the floor at that end of the shop with the Roubo a simple body-rotation away. The arrangement continues to make every day in the shop an unfettered joy.

In addition to the move itself I finally finished the installation of the Roubo’s leg vise after first reducing the thickness of the jaw from three to two inches and reducing the size of the bulbous block that was exactly at knee height and stuck way out into the work space.

To reduce the number of times I whacked it with said knee I tossed the vise screw in the lathe and cut down the outer terminus block by an inch in length, moving the wrought iron collar right up against the handle holes and shaping the end, yielding a result much more to my liking than the knee-cruncher originally made. In fact completing this feature was one of the motivating reasons behind the move.

Using an outrigger stand temporarily until I get the sliding deadman built the bench works just like it is supposed to.

The integration of the massive Roubo into the workspace has other meaningful implications as well, almost like the ripples radiating from a stone being tossed into the pond. Not the least of these effects is the rendering of the planing beam as redundant, clearing up that particular space in the not-too-distant future. I may use part of that space as home to the full-service standing tool cabinet I have always wanted. If so I will have to find a new home for the exquisite vintage mahogany I have stored underneath the beam. Some of the other re-arrangeritis is more subtle as I will build a small, low Roubo bench for the space where the giant Roubo bench used to be. This lower bench will allow me to work for long stretches while sitting. As I get older I find the Eastern tradition of working while sitting down is all the more attractive; I actually do not mind working while standing, it’s the bending up-and-down that wears me out.

All things considered I am thinking that these changes will result in higher shop production-ableness while reducing the total footprint of the space.

Stay tuned.

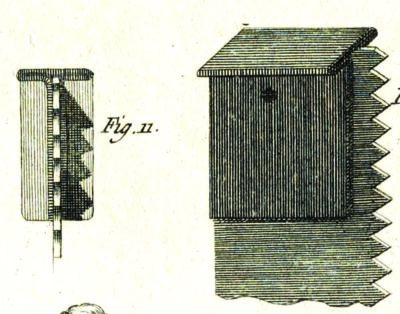

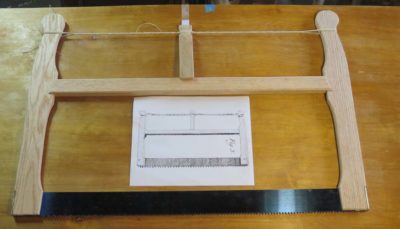

The conceptual foundation of this saw is the ability to rotate the saw blade within the saw frame. When noodling the design and fabricating this hardware element I considered many options before settling on something nearly identical to Roubo’s.

I ordered a variety of of sizes and configurations of eyebolts from McMaster-Carr to play with.

The eye large enough to accommodate or incorporate the 1/2″ cylindrical rod for affixing the blade was simply too huge for the proportion to work properly. The eye of the correct proportion was made for a threaded rod way too small for the 1/2″ wide blade. In the end I took that smaller eye and drilled and tapped it for the cylinder rod of the right size.

I split the eye bolt with my jeweler’s saw and a #10 blade. I then drilled the cross-holes through which the blade could be attached to this split rod.

One of the last things I did before assembling the whole saw was to de-zinc the hardware parts by soaking them in a citric acid solution (about 2 tsp/pint of water). As soon as the mild acid began to work on the zinc the solution got cloudy. I had to monitor the progress and removed the hardware when I had gone far enough.

I assembled everything to make sure it fit but I did not give the saw a test drive since I did not have the saw blade that would be used for it.

I disassembled it and shipped it off to Wisconsin. I cannot wait to get a production prototype back to give it workout.

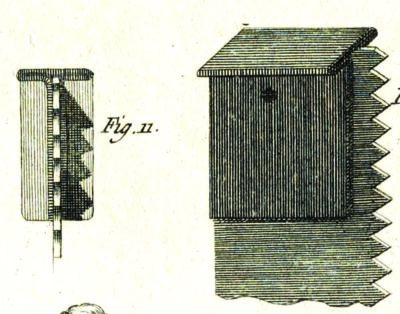

With the Roubo Joinery Saw prototype winging its way to Wisconsin I turned my attention to, well, Roubo’s “turning” saw from Plate 12, Figure 5. I used the identical design for the overall bow for the Joinery Saw, but there were more than enough twists and turns along the road to make it interesting.

The term “turning saw” has two particular meanings. First, the saw plate is narrow enough so that it could be turned as it worked its way through the workpiece. Second, the plate itself could be turned in the bow, enhancing the capabilities of the tool.

I began from the premise used in the Joinery Saw, namely that I would be trying to replicate Roubo as closely as possible based on his illustrations and verbal descriptions. As before I used white oak for the wooden elements. For the saw plate I just used a broken band saw blade since Bad Axe has not yet begun to develop theirs.

Thus the two crucial differences were the housing at the end of the bow arms through which the round spilt post passed, and the split post itself.

The bulbous end block was the simpler of the two problems to solve. I glued scrap blocks in place, laid out the bulb, and shaped it to the design. Drilling the hole for the post was simple enough.

Next time – the split post and related fittings.

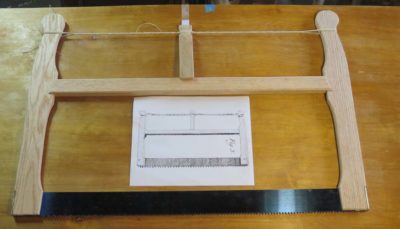

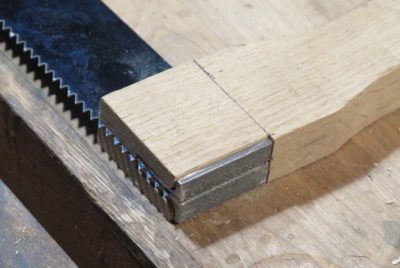

I think that when creating a production-worthy Plate 12, Figure 3 prototype at the request of Mark Harrell of Bad Axe Tools, I spent the most time and creative energy in working out the problem of retaining the saw plate in the bow saw arms.

My first effort two years ago worked well enough for one guy making one saw, but it was IMHO insufficient for any kind of production run. The amount of work necessary to excavate the base of the wooden arm in order to receive this particular two-piece stirrup configuration made this option a non-starter.

Plus, like the configuration of my original Art Nouveau-ish bow saw frame it bore little resemblance to Roubo’s illustration. His description and illustrations clearly represent a folded “T” shaped fitting-with-pin for holding the saw plate in a slot at the bottom end of the arm. So, that is the direction I headed towards. At this point my only fundamental deviation from Roubo was that Mark’s saw plate had two holes rather than Roubo’s one.

I ordered some 1/32″ steel sheet, unfortunately it did not come in narrow configurations so I wound up sawing it by hand until I had pieces that would fit into my little shear/brake. Once I had the strips in-hand I started the process of figuring out how to accomplish this tricky series of bends. Fortunately I had my sweet little shear/brake from Micro-Mark to help me. Sort of.

I found that the brake’s bending was so crisp that the steel snapped off at that point. Actually, what happened is that I could bend crisp 90-degree corners then had to spread them in order to bend the next set of corners, then bend the original corners back. That’s when they snapped. I eventually did figure out how to get it done (see below).

After the steel sheet gave me trouble, before I figured out the solution I tried some .030 copper flashing I had sitting under the stairs in my hardware store. It cut like butter with my engraver’s hook and folded in the brake without a hitch. (I swear I do not know why Photoshop and WordPress cannot play nice with each other!)

Since copper worked so nicely but was pretty soft I decided to try something halfway in between, .030 brass. Unlike the copper it was really stiff so I annealed it on my hotplate before trying to bend it.

By this time I had hit on the solution to the earlier problem that caused the first steel stirrup to snap. Instead of making the first bends to 90 degrees then bending them open, I bent them only enough to establish the corner.

This allowed me to use the brake for the second bend. Then by hand I could fold the unit closed with a hammer and cold chisel until it was in the “T” configuration.

I worked this system in all three materials and found the solution to be darned near perfect.

I drilled out the stirrup and arm to match the holes in the saw plate and held the entire unit together with binding posts. I apologize for not taking a picture of this assembly all by itself.

With the entire stirrup now passing through the bottom of the saw arm there was virtually no joinery involved; just make the slot for the stirrup and plate, widen it a bit, and slip it all together. Inserting the binding posts completed the assembly of the saw and all it needed for working was the windlass and cord. I used a much smaller windlass bar than my earlier one, about 1/3 of the weight of that one.

I took pictures, dismantled it and shipped it off to Wisconsin.

Now, on to Roubo’s Turning Saw.

Aside from the fact that my first effort in producing a joinery bowsaw based on the Bad Axe saw plate didn’t look like Roubo’s, only one of several features rendering this prototype useless to Mark in designing a production run, it was way too heavy at over six pounds. That extra weight was fine for when the saw was engaged but sure was a nuisance when trying to maneuver it in between cuts.

So, I went back to the starting point and recut all of the wooden elements to both be slimmer and look like the saw Roubo illustrated in Plate 12, Figure 3. In the end the only dimension that remained unchanged as the length of the saw plate. Everything else was thinned, widened, thickened, or narrowed as I felt necessary.

The resulting weight reduction of almost 25% was noticeable immediately.

I literally enlarged this image to almost life size when creating the template. Again I used some of my stash of clear white oak left over from the fabrication of the Studley bench top for that exhibit five (!) years ago.

The cutting and configuration was straightforward in the gross sense, but I spent a lot of time getting the template for the end pieces just so, reflecting the illustration Roubo created for the tool. This is a tricky proposition, as the proportions and details of tools are not always perfect (see Plate !! for confirmation) but it had to be closer than the Art Nouveau-ish version I created for the first one. Once I was happy with the shape and proportions of the arms I made a solid template from which I could make as many tracings as I wanted.

Of particular interest to me was the juxtaposition of the stretcher to the end arms; the only way the saw made sense in the flesh was to have the stretcher be notably thicker than the arms. So that is how I made those three pieces. In the end I made the stretcher about 1-1/16″ and the arms 3/4″. I fussed over this detail for a couple weeks.

Notching the arms to receive the stretcher was also an issue as I had to make sure the strength of the arms was not compromised by too large a mortise. I accomplished this by making sure the loose mortise-and-tenon assembly was quite thin, just a bit over a quarter inch and shallow at a half inch. Since the joint’s only purpose was to keep the pieces in alignment that worked out just fine. All the stress was in compression so the tighter the windlass was turned the more solid the bow structure became. Unless, of course, it broke. Hence my fussing.

But that was not the worst of it as noodling and fabricating the stirrups for the end of the saw plate was way more problematic.

Stay tuned.

Some time ago I was asked by Mark Harrell of Bad Axe to build production-able prototype versions of the bow saws Roubo featured in L’Art du Menuisier, Plate 12, Figures 3&5. He was considering adding them to their product line and I was delighted to collaborate with him as I would be with any tool producer.

My first effort two years ago resulted in some success but some failure, so in recent weeks I have been trying to extract more of the former and expunge the latter. My first attempt yielded a prototype that was unsatisfactory in the important aspects of the tool; 1) it was way too heavy, 2) did not look anything like what Roubo described and illustrated, and 3) had plate fittings wholely unsuited for manufacturing (yes, I know I spell wholely different that the dictionary; the dictionary is wrong). So, I went back to the bench and started all over again.

In the coming days I’ll walk you through my successful attempt at Version 2 of the Joinery Saw..

I am delighted to report that after a few weeks of being out of stock, as of ten minutes ago I am now replenished with Model 296 polissoirs and they will begin shipping again immediately.

Ditto the whisk brooms.

Friday was a combination of several benches going together, others being palletized for shipping home, and the completed ones going into vehicles for transport home.

Early in the day the push was on to get together as many criss-cross leg vises as possible.

Once that was done it was time to merge the legs and the top. One group used hot hide glue as a lubricant and adhesive for the joints, even though the latter utility was/is superfluous.

But for most, it was a simple process of placing the top over the leg tenons and rocking the entire unit up and down, switching from end to end. Slamming the entire mass down eventually drove the top mortises onto the leg tenons soundly.

There then began a round of slamming tops followed by proud portraits of the makers and their new benches.

And out the door they went, some on to trucks, others into trailers, and some on to pallets for shipping home.

By 2PM the place was pretty much emptied and the tidying began. Then all of a sudden another FORP was finished.

Day 4 of FORP III was another one of feverish work as the participants were striving to start putting their benches together. Which meant, of course, the final fitting of all the joinery.

One image that was prevalent during the day was sharpening tools to get the joints as crisp as possible; numerous sharpening stations sprouted around the room.

Another snapshot that amused me was this tray of analgesics that was emptied at some point in the day. This was hard physical work, the kind few of us were used to at this level of intensity.

The buzz of activity was the air that we breathed throughout the day.

One of the benches I followed ws the one being built by this father-and-son team, whose tool kit had not arrived for reasons I never quite knew. Nevertheless, I was pleased to make my own kit available to them and they put it to good and successful use.

Meanwhile around the room twenty tales were unfolding and moving towards completion.

This is one of my favorite pictures from the week, with Will providing some useful ballast to Horace’s bench.

Jameel and Jeff provided the real-time, real-space tutorial on installing the Benchcrafted criss-cross leg vise that was part of the package of every bench.

Tim the mechanic was the first guy across the finish line, and hearty congratulations abounded.

John and Phil were next to finish, and I think this will be a treasured family memory for generations yet to come. The excitement was rising for another half-dozen benches ready to assemble Friday morning.

That evening was the open house with a cajun stew for supper, and my Gragg chair on display or anyone who wanted to give it a try.

Day 3 of FORP is pretty much an extended schizophrenic moment as the participants are settling into the routine of work and fellowship, knowing what and why they are doing what they are doing. The morning generally starts out smoothly with restrained purposefulness but as the day goes on there is a palpable edge to the atmosphere as the sentiment, “Oh crap, I’ve only got two more days to get this done,” wafts into the shop.

Wednesday was Mortise Day and the intensity was thick. At the beginning of the day everyone was first wrapping up their base assemblies so they would know where to put the mortises.

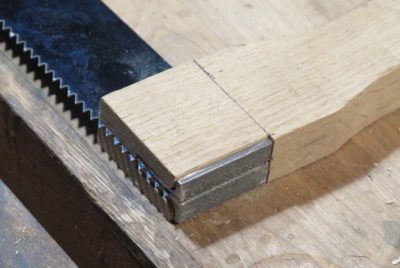

There was a fair bit of tenon trimming also, especially for the dovetailed tenon cheeks.

Oh, and lots of checking to make sure “square” was really square.

Around mid-morning Chris gave the sermon on executing the double tenons. There were two major steps and some folks did one first (sawing the outer dovetailed tenon) and other went the other way (drilling out the waste for the inner tenons).

There was a lot of deep breathing as this was the start of irreversible steps. For the most part everyone had on their game faces for sawing the dovetail shoulders. Except for Brian #4 who was never more than a moment away from a hearty laugh. I think the class had something like five Brians, four Andrews, and three Tims.

Once the angled cheeks were cut the waste was kerfed to facilitate removal.

For the inner mortises the waste was drilled out and for many the edges of the joint were established with a saber saw, a technique I have never employed.

Then the chopping began in earnest.

Somewhere along the line Schwarz encountered this beast of a hand-held bandsaw, using it to trim the ends of the slabs and kerf the outer mortises.

I included this picture just because the wood was so remarkable.

Yes indeed, the joint was jumpin’ this day.

Recent Comments