My recent trip to Indiana to teach for a week at the Marc Adams School of Woodworking coincided with one of the monthly “open houses” at the World Headquarters of Lost Art Press in Ft. Mitchell, KY. I had a grand time there, visiting with many fellow woodworking enthusiasts.

I was especially delighted to cross paths with Dr. Mike, a specialist in hand and wrist injuries, who has been advising me on my rehabilitation following last year’s broken arm. The location and severity of the break made its manifestation a wrist and hand issue. The radius had snapped about an inch above the wrist and the broken-off tip had rotated considerably. Fortunately the setting went perfectly. (Note to self: don’t fall onto a stone walkway any more) The resulting cast was necessarily quite snug to keep everything in order, and the posture of the hand was not straight but rather considerably bent to keep everything in proper alignment during the healing. One result of this arrangement was that all the swelling was pushed down into my fingers, which for several weeks looked like kielbasa. As a result of all this, the directed swelling really aggravated the arthritis in my hand, which x-rays confirmed infest every single joint therein.

After getting the cast removed I undertook a rigorous regimen of physical therapy emphasizing flexibility and movement and downplaying the regaining of my hand strength. I attacked the problem, which seemed to be resistant to my best efforts at resolution.

Enter Dr. Mike.

At last March’s Lie-Nielsen event on Covington KY he examined my arm/wrist/and and declared that I was being too diligent in my exercises; I was working the region so hard I was essentially inflicting as much inflammation as I was alleviating. He proposed a new exercise routine for me, which I began the next day. The beneficial results were almost immediate, but still the road to full recovery had many miles to go. We corresponded regularly as I provided updates and he provided further counsel.

Flash forward to the LAP open house, when he gave an exceeding thorough evaluation of the damaged flipper. We were both every pleased at the progress, and changed the emphasis to the return of ultra-fine motor skills in the digits. With a new set of exercises to address this we parted and I have been engaged in additional finger flexibility routines ever since.

At this point the overall status of the ensemble varies on a day-to-day basis of somewhere in the 85%-95%+ range. My arm bone is fully healed and needs no more thought. My wrist flexibility as close to 100% of that which was expected. My finger micro-dexterity is somewhere north of 75% depending on how my arthritis is acting up. Some days it exceeds 90%. My hand strength is in the 80-90% range and slowly getting stronger with ordinary shop activities.

I recently wrote a note to Dr. Mike celebrating my use of chopsticks for the first time in over a year. Indeed I mark the progress by the little things I can do again; remove the gas cap from the car without discomfort, pull the starter cord for the log splitter, handle the chain saw, hand plane and hand saw with impunity.

As the day in Ft. Mitchell wound down the stragglers mostly gathered to watch Chris work on a chair seat.

Finally it was just a handful of us, as we ate pizza and then I hit the road.

Recently I was reviewing the manuscript for Joshua Klein’s great new book about polymath and furniture maker Jonathan Fisher for Lost Art Press as I had been asked to write the Forward. The book is an excellent reading and learning experience, and one of the descriptions of Fisher’s day-to-day life caught my particular attention. In addition to everything else he had to do was the onerous task of obtaining many tons of firewood requisite for each Maine winter.

My friend Bob, who is a lifelong timberman, came for couple hours a few months ago and felled more than a dozen large ailing trees that had been damaged over the years. His help is incalculably important as I simply do not have the experience necessary to fell very large trees with confidence, while he has felled literally tens of thousands of trees and manages to drop them safely right where they need to go. Among this year’s prizes was a wonderful old oak with a long, straight trunk, that had been damaged in a storm last winter. I’ll be splitting and riving that one in a few weeks, I hope. More about that later.

Sometimes we just go where the trees are, but I am particularly interested in thinning the woods to the south and southwest of the barn to perhaps extend the daylight portion of winter days by an hour or more. Currently I lose direct light by about 3PM and I aim to push that to 4 or 4:30. That will be the best I can hope for unless we remove the crest of the hill occupying that space.

Once the trees are on the ground I can then return at my leisure to cut them into bolts and haul them down the hill. Inasmuch as I have the same objective as Jonathan Fisher, gathering tons of firewood each winter, I am more than delighted that almost a century ago the good folks at Stihl, Dolmar, and Festool worked independently to provide us with what we now have as the modern chainsaw. Ditto whoever combined a gasoline engine, hydraulic piston, and steel wedge to create log splitters.

With the side crib completely full with a double course of wood and the front porch filled with only a walking path to the front door we are ready for winter. I’m now working on my firewood pile for next winter with hopes of eventually getting a couple of years ahead. It’s the mountain way.

For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counseller, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace.

The angel went to her and said, “Greetings, you who are highly favored! The Lord is with you.” Mary was greatly troubled at his words and wondered what kind of greeting this might be. But the angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary; you have found favor with God. You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over Jacob’s descendants forever; his kingdom will never end.”

Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? Isn’t his mother’s name Mary?

And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God. And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.

I pray for you to have a blessed time with loved ones, and that you are celebrating the Incarnation, through whom we can be reconciled with The Creator.

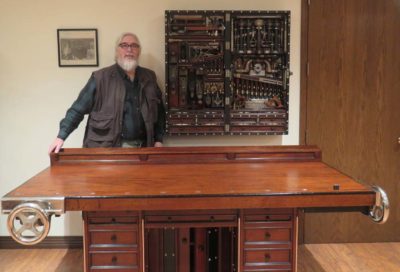

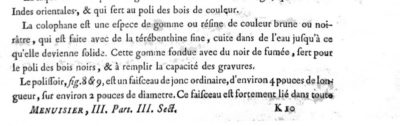

A while back I had the opportunity to visit some old friends, namely Mister Stewart and his remarkable collection of artifacts including the tool cabinet and workbench of HO Studley. My impetus for the visit, beyond the obvious, was to examine the newest element found and integrated into the workbench. The rear shelf completed the composition of the bench.

It was unusual for the form in that it was not pierced to hold tools, the typical arrangement for such shelves, such as this analogous bench and shelf.

Perhaps the function of this shelf on Studley’s bench was to simply look pretty?

Another element of the visit was documenting more fully some of the molding profiles on the cabinet. Though I did not have a profile gauge with me, Mister Stewart gifted me with a piece of the molding he made when he fabricated the new workbench base. Once I get that photographed I’ll post that as well.

Now that we are on the verge of big time heating season I can reflect on the new hearth pad I made for the wood/coal stove in the basement of the barn. In the past, due mostly to the fact that the stove was installed in the dead of winter with near-zero temps, the pad for the stove was simply loose firebricks laid on top of the plywood sub-floor. It had remained that way for four years until I revisited the situation over the summer.

I removed all of the loose firebricks except for the four underneath the stove feet and a row around the perimeter and hand-poured a concrete pad (reinforced with hardware cloth) in its place. I don’d know if it will make any difference but it makes me happier to have it done.

It is pretty clear from the results that I am not a mason or concrete specialist. Regardless, it is ready to go and provides a permanent foundation for the 500-pound stove for as long as the barn is standing.

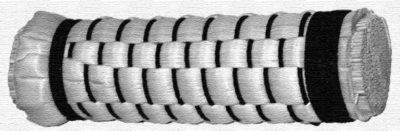

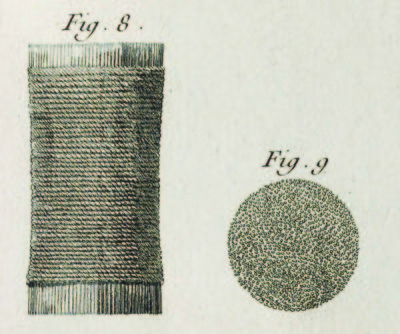

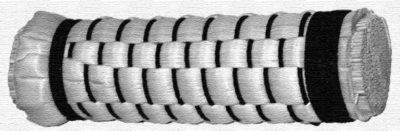

With the new Juncus polissoir made I took a minute to examine and characterize it, and give it a quick test drive. As I said earlier, it took a lot more of the rush to compress to the same density of the sorghum polissoirs I have made for me.

My immediate impression of the Juncus polissoir is that is softer and more fragile than the sorghum. The working surface just seemed softer to my fingertips and fingernail, and the fibers around the perimeter of the working tip were much more easily damaged and broken off. My deduction is that this tool could not be used vigorously as a dry tip, unlike the sorghum. Yannick Chastang implied as much when he indicated that this tool is always used with wax, although Roubo is less clear on the subject (Roubo could be a frustrating writer, often accomplishing the nearly impossible feat of being simultaneously effusive and laconic).

Due to time limitations, at that moment my only side-by-side apples vs. apples comparison I could make was to use a dry (unwaxed) sorghum polissoir and this new dry (unwaxed) Juncus polissoir on a prepped board.

Both accomplished glistening surfaces in a matter of seconds.

The visual result was pretty much indistinguishable, but there was a definite sensory difference; the Juncus polissoir seemed much softer to the surface of the wood. Even though the fibers of each were compressed as tightly as possible, the sound of them tapping on the workpiece differed; the Juncus had a much softer, more diffused sound than the sorghum. Deductively this implies that the sorghum polissoir was more efficient to Juncus in burnishing (compressing and smoothing the surface of the workpiece), yielding a “brighter” surface, but the Juncus might be superior in polishing (smoothing via rubbing abrasion) and also more forgiving. Neither strikes me as “superior” overall at this point, they just have unique characters that differ. I do suspect also that the sorghum polissoir is more robust and long-lasting than the more fragile Juncus, but that may or may not be true, and might be mitigated through wax impregnation.

As time allows in the future I will test and compare these tools further in the future, but for now that is what I have to report.

Once the Juncus dried enough for me to play with, I trimmed a large hank to length, about 4-inches.

Just to make sure it was really dry I placed it in a glass canning jar on top of my coffee warmer glue pot for 24 hours. Then I started to make a polissoir as I have done many times before, albeit with sorghum broom straw.

One thing that is immediately apparent is that Juncus is much less dense and more fragile than broom straw. This is not a surprise give that Juncus is a hollow rush, essentially a tube structure. When assembling the fibers for constructing the polissoir I did something I had not done before, I flipped half of the fibers and then shuffled them for a fairly even distribution.

Grabbing a handful from the case of hose clamps I keep on the shelf for maintaining the hydroelectric penstock, I lined everything up and started tightening. And tightening. And tightening. The hollow feature of the Juncus meant that the collapse of the bundle was dramatically more than the broom straw. While the broom straw compresses about 10-20% under clamping, in my gross observation (I did not measure it in advance) the Juncus compresses 50-75% to achieve the same density as the corn straw. In other words, Juncus compresses somewhere between 2-1/2 and 7-1/2 times more than sorghum.

Once the bundle was tightly bound in the hose clamps I began to wrap it with heavy waxed linen cord until it was complete and tied off.

One one end of the polissoir I trimmed the tip with a Japanese knife; on the other I used a fine saw to cut off the excess.

Now it was ready to put to the test.

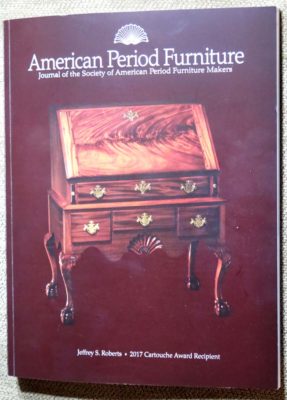

I rarely post about something that is current, but I found a package on the front porch when I came down for lunch yesterday. Inside was the new issue of American Period Furniture, the annual journal of the Society of American Period Furniture Makers. I have been a member of SAPFM for many years, and served a couple terms on the Society’s governing body.

Last year I was invited to be the banquet speaker for the annual Working Wood in the 18th Century conference at Colonial Williamsburg. Since the SAPFM always holds their annual business meeting and banquet at this conference there were plenty of members in the audience that evening.

They must have liked the banquet talk because I was immediately asked to turn it into an article for APF. I did, and it arrived this week. I forget whether this was my third or fourth APF article.

I will be blogging about each the 10 exercises in the talk and article at greater length in the near future.

One day at lunch last spring I mentioned to Mrs. Barn my correspondence with Yannick Chastang and my subsequent interest in finding some Juncus rush to experiment with making a polissoir from this fiber. Where, oh where, could I find this exotic plant?

“Out back, it’s all over the place,” says she. “We have some here along the pond.”

Immediately after lunch we went together to walk around the pond and she pointed out the few immature clumps of this spikey plant. This was one of the hundreds of wetlands grasses, in our case Juncus effusis. After looking it up I concluded that its geographic growth range is limited to planet Earth. Apparently it is almost universal in its growing. Maybe even the river banks of Paris?

Cheered, I went back to work and after some more correspondence, knew I had to wait until autumn to harvest it.

Flash forward a few weeks to my chatting with stonemason extraordinaire Daniel as he was creating our new stone wall.

“Come over to my place, ” he said. “I’ve got a ton of it around the pond. Help yourself. It’s just a weed the cows won’t eat.”

Now I was getting really jazzed.

Flash forward again, this time to September when my friend JohnH came to help teach a workbench-building workshop. Since no one showed up to build a workbench we spent most of our week in great fellowship working on the ripple molding cutting machines, which he and I will be demonstrating at the upcoming Colonial Williamsburg Working Wood in the 18th Century shindig, we took time to go to Daniel’s and harvest a pile of the “weed.”

We spread it out to dry in the sun for three days, then I bundled it up and moved it inside to finish seasoning.

Before long it was ready to work with.

The polissoirs I commission from a local craft-broom-maker employ the materials with which he normally works, namely broom straw (sorghum) and nylon twine, with woven outer sheaths. It makes perfect sense given the scale that Polissoir, Inc. has become; he needs to use materials and techniques with which he is familiar and facile, and for which he has (for the moment) a sorta-reliable supply of raw materials.

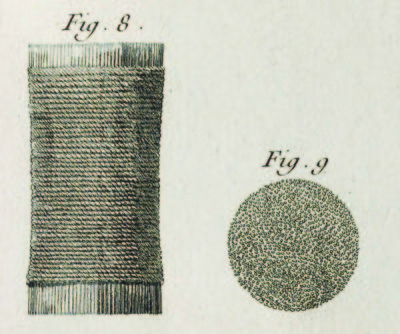

The only variance from this is the Model 296 polissoir first commissioned by Thomas Lie-Nielsen for sale through his enterprise. In this version, made as close to the original description in L’art du Menuisier as is practicable, the outer sheath is a wrapped linen cord rather than woven sorghum.

In reviewing the sorghum polissoirs (and To Make As Perfectly As Possible) marqueteur Yannick Chastang chided me for mis-identifying the fibers used in traditional polissoirs, asserting that the genuine article used a wetlands rush rather than sorghum, and that sorghum broom straw was an inferior material for polissoirs. The first point is certainly a fair one, the second is a judgement/preference call I will discuss in a subsequent post. It’s like saying a Ruger 10/22 rifle is superior to a Smith and Wesson .50 caliber revolver. It depends on what you are trying to accomplish with the tool.

In the original text, Roubo uses the term “de jonc ordinaire” (common rush; the connection of “de jonc” to “Juncus” is not a great leap) for the plant fiber used in polissoirs. Our dealing with that term highlights the difficulties of a translation project (and explains the reason this is a very slow writing process), especially when the primary meaning of words mutates over time. Although French was probably the first codified modern language, it has changed little in the past three or four centuries, the hierarchy of definitions for words has definitely shifted. Words for which the first definition might be XYZ in one time period might find definition WYZ to be the second, third, or even eighth-ranked definition in an earlier or later dictionary. This is a struggle Michele, Philippe, and I wrestle with continually as we work our way through the original treatise. Dictionaries roughly contemporaneous to Roubo declare that the word “de jonc” can mean reed, rush, straw, grass, hay and several other definitions I cannot recall at the moment. But Yannick’s assertion that I chose the wrong word in English based on my editorial discretion is certainly not unfair.

With that idea in mind, I set out to explore the topic more fully. One problem, though, resides in the question, “Which Juncus?” After all, this is a huge genus consisting of several hundred species.

And, where would I find it?

Stay tuned.

Recent Comments