You have no doubt heard the old aphorism that, “A weed is just a flower in the wrong place.” The same might be said for commercial products in the marketplace, that they are sometimes useful but for different (read: wrong) things. For example, for years the family who owned the hardware store I patronized were uncertain what I did for a living, they only knew from our conversations that I bought products from them and used them (successfully) for unintended purposes. This adaptability is only one of the reasons why comprehension of materials science is fundamental to craftsmanship.

Of the products in my studio, perhaps the best that fits the “weeds” description — right product, wrong use — is Safest Stripper from 3M. It was/is marketed as a “environmentally friendly” general use paint and varnish remover, and when it performed poorly in the shops of antique restorers it got a bad reputation, at least in my circles. Perhaps unbeknownst to the 3M marketers, and certainly in the experience of the antique restorers using it, Safest Strippers is certainly not a high performance general purpose stripper.

But, it has a unique advantage in the shop that I find irreplaceable.

This usefulness is based on the original formulation and purpose for Safest Stripper. As I recall the history, Safest Stripper emerged from the world of aqueous solutions of dibasic esters (DBEs) which work gangbusters on many catalyzed coatings, airplane and auto paint in particular (I vaguely remember a conversation at a meeting of the American Federation of Societies for Coatings Technology that DBE solutions were created specifically for the catalyzed paint Imron, but that conversation was a long time ago). In my experience it also works pretty well on polyurinate, some polyesters, alkyds, and acrylics, somewhat less well on cellulose nitrate. Conversely, it has almost zero effect on natural resin coatings and natural oleoresinous coatings. Dealing with these latter two classes of paints and varnishes happens to be a huge component of antique restoration, so its ineffectiveness on them explains its unpopularity with many restorers.

I found that the primary feature, affinity for catalyzed and synthetic materials while leaving alone many older traditional coatings, along with the near-zero volatility of DBE solutions, makes Safest Stripper an absolutely perfect fit for those times when I need to safely remove, in particular, aged white and yellow glues that have been slathered on many a bad repair attempt.

That makes Safest Stripper an irreplaceable high-performance tool in my kit.

In a couple days I will recount how I use it in projects, with a photo montage of procedures and results.

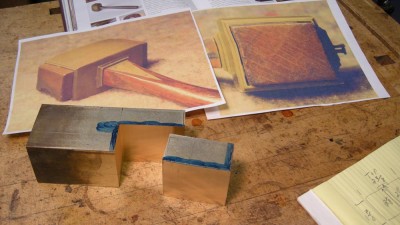

No commentary really necessary as we glimpse the tiniest drawers inside JimM’s replica of the Studley Tool Cabinet.

The genesis for this box goes back to my earliest days in the trade, when I got caught in the middle of a p!$$!ng contest between a cabinetmaker and a finisher in the shop where I was working. They were both opinionated and passionate about most things in the shop, but the real nexus of conflict for me was their insistence that there was a way, and only one way, to portion and use sandpaper. How was I to know it was a Battle Royale? It’s just a stupid piece of sandpaper!

The cabinetmaker insisted that a full sheet of sandpaper be creased on the center line of each axis, torn to the center of the sheet along one of those crease lines, then folded so that the four quadrants were stacked on top of each other when the sheet was folded. The finisher was equally adamant that the full sheet of sandpaper be cut in half along the short axis, with the remaining halves being folded in thirds for use. Being 16 or 17 at the time with no time in the trenches, my response was to try diligently to remember to simply use the sandpaper the same way as whichever of the psychopaths I was working with at the time.

Over time I gravitated to the half/thirds strategy of the finisher.

In recent times as my scale of work keeps getting smaller and smaller I struck out on a new path that disagreed with both of these cranks.

Yes, I now start by cutting a full sheet of sandpaper in half along the short axis.

Then I cut each of these halves into four equal pieces, divided along the short axis of the halved paper, yielding eight identical pieces per full sheet. I generally then take each of these 1/8 sheets and either fold it into three sections or cut it into three sections.

To use the small sandpaper pieces on the surfaces I fashioned a group of sanding blocks to work perfectly with the new size.

I made several dividers for the interior of my sandpaper box (purchased recently at a Cincinnati flea market), and filled it with paper in the following grades:

80 grit garnet/AlOx

120 grit garnet/ AlOx

150 grit Tri-M-ite silicone carbide

180 grit garnet/AlOx

220/240 grit Tri-M-ite

320 grit Tri-M-ite

400 grit Tri-M-ite

In identical spaces I include the following wet-or-dry silicon carbide paper:

220 grit

320 grit

400 grit

600 grit

1500 grit

I love this new arrangement as it makes the sandpaper easy to find and grab, and I see that my pile of “scrap” sand paper is much smaller. I also discovered that with these small pieces of paper I find myself switching off much more frequently to new sand paper rather than trying to “get just a little bit more” out of a bigger piece before I throw it away. Using sandpaper too long is counter productive in three ways; first, once the grit is gone any further effort will not accomplish much, it burnishes rather than abrades; second, “worn” sandpaper gums up a lot and imparts new problems to the surface; and third using sandpaper too long and on multiple projects leads to cross contamination headaches.

Once I get some time, perhaps this summer, I will put a proper japanned finish on the box. But for now it just sits on the work bench and gets used a lot while I get a smile on my face each time I reach for a new piece.

Who knew that both of those guys were wrong?

Sleepless Jim has sent many pictures of the drawers and their contents. The tools and accouterments contained inside ares sometimes identical to the original Studley Tool Cabinet, and sometimes more reflective of Jim’s interests and needs.

I note with interest his insertion of a mother of pearl button into the pulls for the drawers. It is an inspired touch, and I have mused about HO not doing the same. It would have been so like him.

I’ve written before about the usefulness of spring clothespins in the shop. I keep a shoe-box sized container pretty much filled with these irreplaceable tools in the shop, and it is indeed a rare day when I do not reach for that box a time or two. I recently had a project of reassembling some damaged fretwork where I needed some gentle clamping with a dimension exceeding the opening of the original clothespin throat.

So, I made some Frankenpins. They did the job perfectly. I cut off the business end of some pins and glued them to another pin with hot hide glue.

Cost? Two clothespins = 8 (?) cents. Time? Hmm, I was a bit slow at the time so I think it took me almost a full minute for each one, but I did wait over night for the glue to dry.

I’m betting these will get used more than I can imagine at the moment.

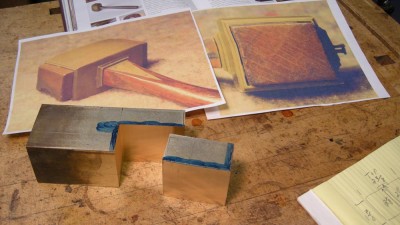

Sleepless Jim practically sent me over the edge with this offering, using Brazilian Rosewood for the handle and tight beech infill salvaged from an old transition plane. As if I wasn’t already eager enough to make replicas of this, my favorite tool in the collection.

And yet, there is still much more to come.

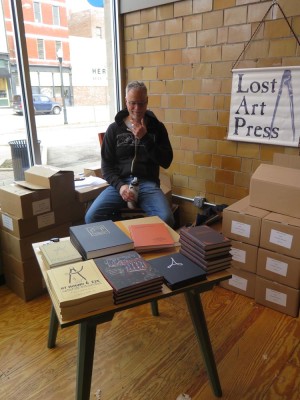

Thanks to the brutality of vengeful garden implements six months ago I was able to attend both the Lie-Nielsen Tool Event in Covington KY and the Grand Opening of the Lost Art Press World Headquarters recently. You see, I had been scheduled to be in Cincinnati to shoot two instructional videos the first week of September 2015, but the resulting injury from the Attack of the Killer Wheelbarrow precluded my availability for that session. F&W Video Producer David Thiel assigned me the next available week of studio time, which turned out to be March 7-11, 2016, and once I was up and about I began to focus my preparations on that time slot.

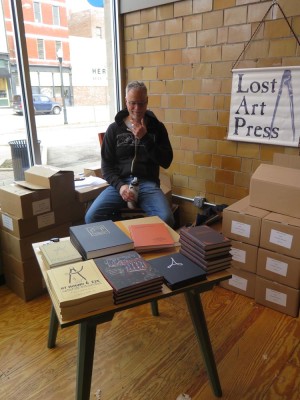

In the mean time LNT announced their event and Chris and Lucy fulfilled their life-long dream with the purchase of the building that was to become the new home for Lost Art Press. When I arrived in town ahead of the shooting I had a bit of free time so I drove by the new World Headquarters and it was as useful and charming as Chris had described. The neighborhood was exactly what they wanted, which is a true delight (it is too claustrophobic for me, I like my nearest neighbor’s proximity to be measured in football-field-lengths if not outright mileage).

Come Saturday morning I was able to walk the streets of Covington and drop in to the new store front as it was open for the very first time. Not surprisingly the foot traffic was steady and enthusiastic.

Taking pictures of the space was a challenge because there were so many folks coming to visit the Schwarz Mother Ship. But with a little patience I finally got a nice pic of the bench in the center o the space and the wall unit that had served as the backdrop for the bar when it was still an establishment of refreshments.

After the conclusion of the LNT event few blocks away, the crowd began to gather at LAP for the evening’s Grand Opening festivities. I was delighted to get a little time to chat with Lucy, who was radiant in talking about living out this dream. But then I have never seen Lucy when she was not radiant and enthusiastic. I also spent a lot of time visiting with folks who were enjoying the fruits of our collaborative labors through the Roubo and Studley books. But mostly it was a time of fellowship conversing with people about the topic of woodworking that binds us together.

I stayed as late as I had the wakefulness for, then headed back home after a good night’s rest.

As I delve more deeply into urushi lacquering techniques (sans the urushi itself due to allergies) I have found a couple of fascinating youtube channels to browse. But, be warned! I find that once I start watching a series of these, time simply disappears. Literally, I can sit and watch these for two or three hours at a stretch. Two weeks ago we were visiting friends in Knoxville, and my pal Dave raised an eyebrow when I told him about these.

He puled it up on his television and an hour later the ladies had to come and break up the party so we could have supper.

The best of these channels is named fushimiurushikobo after its creator and host Maki Fushimi, a classically trained urushi artist who is still very active in the creative community. Since lacquerwork is pretty spatially contained, I think he is simply setting up his laptop so that the camera is in the right place and starts recording. The videos provide nearly no instruction beyond the occasional brief on-screen text, with no narrative or sounds other than the ambient sound of him working. Occasionally you will hear something in the background, but it is definitely low aural sensation.

Mr. Fushimi documents a number of projects, including lacquer harvesting and processing through the creation of his many urushi artworks.

I find them to be not only delightful but densely packed with visual information to guide and direct my own efforts in this arena.

A second youtube channel is the one dedicated to the lacquer artist HISAYA TSUKIJI. It seems to be similar to Mr. Fushiim’s but I have not worked my way through it very much. But what I have seen I like very much, as he is approaching the art form from a different direction.

If you find any other urushi video resource you find especially useful, let me know.

A week ago at this time the Lie-Nielsen Tool event at Braxton Brewing in Covington KY was just about over. I was able to spend some time on Friday afternoon after clearing out of the video studio for Popular Woodworking, then again Saturday afternoon. Saturday morning I had taken advantage of the relaxed schedule and proximity to population centers to sleep late, have a great omelet for breakfast, and go to a good art store to purchase some supplies.

The setting for the Lie-Nielsen event was nirvana for many woodworkers; perhaps some of the finest tools in the woodworking universe and craft brewed beers in the same place. Not being a beer drinker some of the setting was lost on me. I did have my first bottle of soda in more than three years, though. Orange Nehi. Ahhhhh.

It was great to renew old friendships and acquaintances and make new ones. There is no doubt that my Virtuoso collaborator Narayan and I were the coolest dudes there in our fabulous Optimo hats. Nobody else came close.

In addition to the crew from LNT and their entire line of tool opiates, another half dozen or more superb tool makers were in the house, along with the Lost Art Press guys and a rotating roster from Popular Woodworking. The Brewery was set up with a large-ish space off to the left once you entered, with another sizable alcove at the center rear.

Chris Kuehn of Sterling Tools was in the immediate line of sight once you entered into the facility. Of course we chatted but it seemed like every time I looked Chris was surrounded by questioners and customers.

Physically closest to the entrance was a maker of superb planes I was unfamiliar with, was Mateo Panziea of Lazarus Planes in nearby Louisville. Reatively new to the full-time world of toolmaking Mateo has a broad background of craftsmanship, including a stint in the art conservation world from whence I emerged. His planes were robust and excellent quality, and I came this close to pulling the trigger on a small low angled smoother that would have been perfect for finishing up parquetry and marquetry panels. Once again I am struck by “not buyer’s” remorse.

Next to Matteo, in the corner, were John Hoffman and Chris Schwarz of Lost Art Press. It was a big weekend for them as it was the official release of Chris’ new Anarchist Design Book (I do not particularly care for the whole anarchist theme as Chris uses the word close to properly but 99% of the populace does not). Not surprisingly with two new offerings they were doing a good business.

Moving around the front space we come to the workbench shared by the nonpareil plane makers Konrad Sauer from up in that there Canada, near Toronto, and Raney Nelson from the equally exotic Indianapolis area. Their tools set the standard for the new wave of woodworking toolmakers, and I am happy to report that increasingly their compatriots in competition are picking up the gauntlet.

The PopWood table served as a transition from the front space to the rear space, filled in great part by the LNT inventory with demo space for Daneb and the crew and all the visitors to try out all the tools. And they were!

Caleb and Konrad deep in bevel angle contemplation, no doubt.

Along the back wall were the stations for the SAPFM Ohio River Valley Chapter staffed by old friends of mine, and a workbench shared by Caleb James and Tod Herrli. I do not yet own any of Caleb’s planes, but do have some of Tod’s (with more to be made for me, he is only awaiting me to send him the wood I want to be used for the plane bodies).

Turning the corner we find a couple of young tool makers, Walke-Moore, with whom I did not have time for conversation, but again their table seemed to be mobbed.

Next came perhaps the most pleasant surprise of the weekend as wooden body plane maker Steve Voight was showing his wares, and they were excellent. But that was not the surprise as it turns out that Steve, a composer by day and plane maker by night, lives fairly nearby. We plan to get together as often as possible.

The final station of the tour belonged to Scott Meek, wooden bodied plane maker whose aesthetic vocabulary is all his own. It was a delight to see Steve Voight, working in very traditional style, alongside Scott whose work is definitely not but yet magnificent in its own high-performance sleek and streamlined way. Somehow I fails to get an image of him and his planes. Sorry Scott.

As the festivities at the brewery wound down I walked with Brad D, one of the original Fellowship of the French Oak Roubo Bench members, down to the new LAP World Headquarters for the evening’s festivities.

Once again, when Jim could not find the exact right thing to outfit his replica of the HO Studley Tool Cabinet, or did not already own it, he created it.

Recent Comments