Recently I was interacting with renowned plane maker Konrad Sauer about something completely unrelated to woodworking (although it was really neat and gratifying, but I will probably let him blog about it in more detail). Konrad is one of the small band of premier metal-bodied plane makers I know, along with Raney Nelson and Ron Brese, who are setting the standard for the renaissance of infill planes. Thanks in great part to my brief time with Konrad I was prompted to dig out a few of the Toolapalooza 2015 treasures I’d stashed away for restoration “some day.”

An attendee to a workshop at The Barn once brought one of Konrad’s planes and the hook was planted. Over the years I’d given little thought to infill planes until more recently when my acquaintances with these plane makers, and more importantly experiencing the sublime quality of their tools and the results they imparted, encouraged me to explore a bit further. Rather than diving in whole hog for the price of a new Sauer&Steiner/Daed/Brese plane (none of them affordable to me no matter how hard I might dive) I did what I often do with new notions. I bought several old beaters at Martin Donnelly’s 2015 summer auction. Actually I bought three beaters at about $11 apiece, and one very fine c.1800 London infill miter plane that was a fair bit more than that. More about that one later.

This intermittent series of blogs will address my reclamation of this group of planes, beginning with an unmarked D-handle smoothing plane of unknown vintage and origin. But it was complete and intact, bore no obvious scars of abuse or damage, and seemed a great starting point in this journey. Fortunately since this plane was complete though battered, the restoration — although transformation might be a better word since it bears little resemblance to its former self — took only a few hours spread out over several days and interspersed with other activities.

Stay tuned.

Last week was pretty much dedicated to begin readying the homestead for the upcoming winter, which the almanacs predict will be brutal. My goal is to eventually get at least a dozen cords (we will need about six for the coming winter) and I am about a third of the way there, so every day was spent cutting, splitting and stacking tons of firewood, and the chimney man came to clean and examine the two chimneys in the cabin. Excellent report there.

On top of that the daily harvest from the garden is a thing to behold and those bounties are gathered and processed by Mrs. Barn, and plans evolve for expanding and preparing the gardens for next year.

Even more on top of that we picked up our new brush mower so that when I have nothing else to do I can start/continue the clearing of the hillsides adjacent to the cabin and barn.

Thus far this machine has revealed itself to be all that we hoped it would be, and since I can set the forward speed to pretty slow it is fine for my hip to make the trek behind it. It does require a fair bit of shoulder and arm strength to keep it on the straight path while hogging through the underbrush. The results are pretty impressive.

If all goes well I can resume my regular time in the shop now, and spend an hour or two at the beginning and end of the day continuing the tasks of assembling the tons of firewood or clearing the homestead in preparation for expanding the gardens and planting some fruit trees.

Rural life is great, especially when you can harness electrons and internal combustion.

One of the very special moments in the recent Parquetry workshop at the barn was when we were walking past Jim’s car and he said, “I have something for you.” He opened the trunk and handed me a package that was Irish Whiskey. I mentioned that I was not much of a drinker but knew this to be very good stuff. “Well, open it to make sure you like it,” he replied.

I did and my eyes bugged out and my heart went a-flutter. It was a replica of the mallet from the HO Studley Tool Cabinet, identical to the one Jim made for himself as he was assembling the contents for his Studley 2.0 unit.

“I couldn’t sleep one night so I made this for you.” I wish that my sleepless nights were as productive as his. He machined the brass shell and fashioned the beech infill from the salvage of a transitional plane, and the handle is magnificent Brazilian rosewood. It is simply exquisite and becomes part of my treasures in the HO Studleyana Menagerie.

That collection started with Narayan’s gift of a hand-processed image that began as a lark and ended up as one of the most popular images in Virtuoso. Soon it was joined by the remarkable Studleyesque hammer-and-caliper holder fashioned by OldWolf himself, DerekO, complete with period-appropriate ebony-handled hammers and the Veritas replica of the caliper used by Studley.

The collection occupies the most prominent location in our home, namely the center of the solid chestnut mantle above the wood stove in the living room.

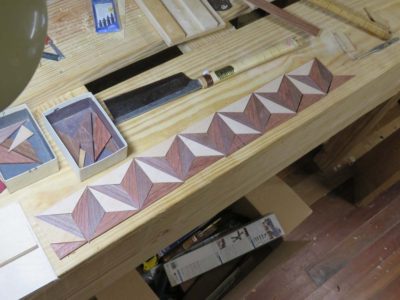

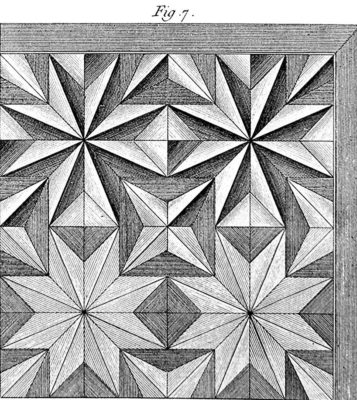

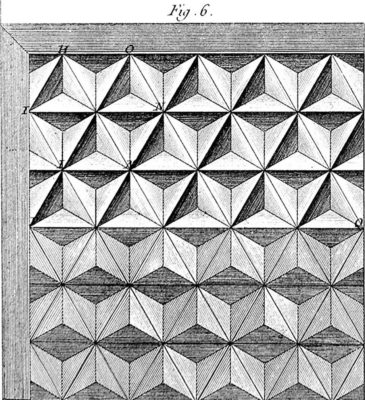

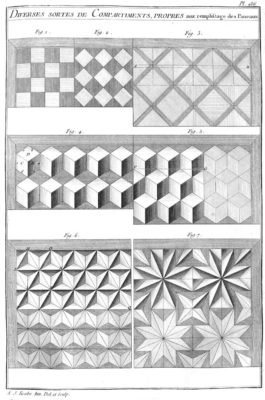

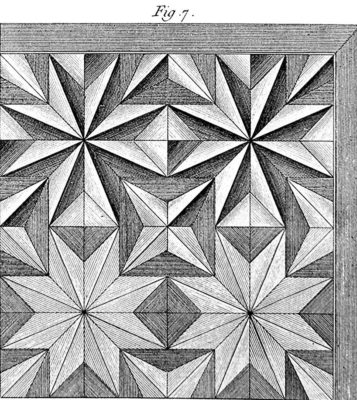

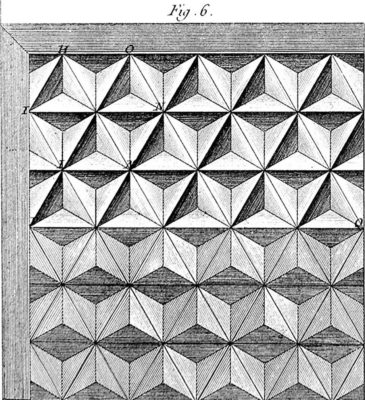

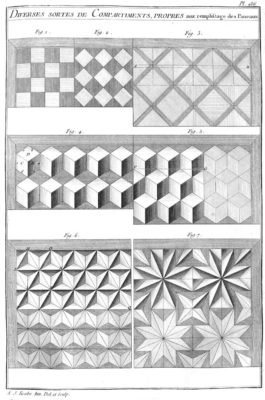

With the first pattern exercise completed the participants followed my lead and began the work on the second exercise, that being from Plate 286, Figure 6.

Basically it is a twice-as-complicated off-shoot of the more staid Figure 5, consisting of larger units composed of three isosceles triangles that are 30-120-30 in configuration.

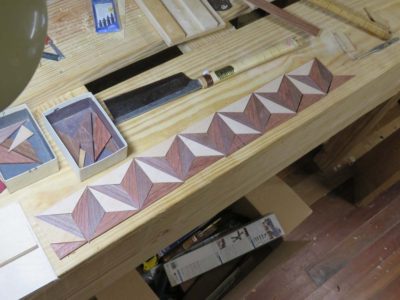

Jim found it especially challenging to work with pernambuco, the orange tropical hardwood that was so dense we wound up making a special jig so it could be cut on the table saw.

The design lends itself well to three separate species being used, and this expression can be subdued or vibrant. Due to time constraints we only glued these down to the paper supports, and each person could then mount them permanently on a substrate panel once they got home.

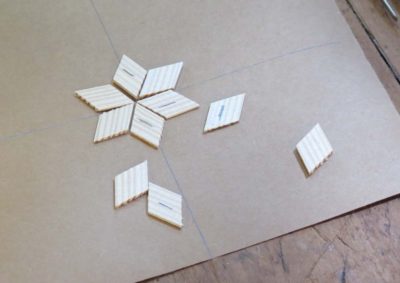

As we moved on the the final exercise we simply ran out of time so all we got done was me showing the use of my own jig and providing them with the materials and instructions for their own to make at home.

I believe a grand time was enjoyed by all, certainly by me, and I look forward to teaching this workshop (or one very similar, perhaps with slightly different exercises) again next summer at The Barn, and next autumn at Marc Adams School of Woodworking.

Last weekend was the final workshop at The Barn for this year, a 2-1/2 day exploration of 18th Century Parquetry as documented by Roubo. It was great fun with four engaging and gifted woodworkers present to make it a bunch of fun. Gerald from PA was the first to arrive Friday morning, Glenn from TX arrived just before lunch after traveling for more than 24 hours (his flights were sidelined by the weather at DFW) and Lou and Jim arrived from NC just as we started at 1PM. My camera battery was dead so I had very few pictures from that first half-day.

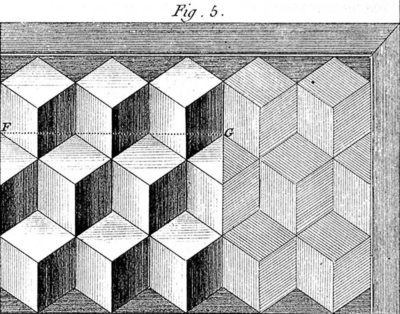

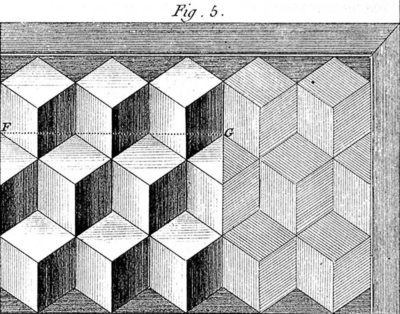

Using the simplest of tools and supplies — a 30-60-90 triangle, and some small pieces of baltic birch plywood — we got our first of three sawing/planing jigs built in order to create the first exercise of the easiest non-rectilinear patterns from Plate 286, Figure 5. Once the jigs were done we planed and re-sawed the southern yellow pine we were using.

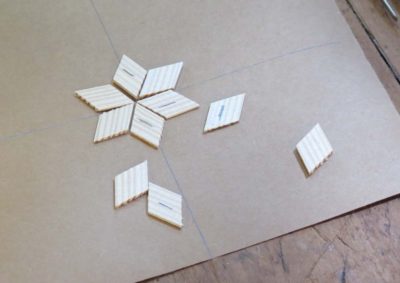

Then the work began in earnest as the task was to first cut and plane-trim to uniformity as many equilateral 60-degree parallelogram lozenges as possible (this pic is from a later exercise but the trimming with a block plane i the jig is essentially identical), then begin the oft-times confusing task of assembling the pattern.

Once you get the hang of putting the pieces together it goes quickly, but at the beginning there is much exclamation and flipping of individual pieces.

Quietness punctuated with an occasional expression of aggravation reigned for a couple of hours as the lozenges were glued down to brown paper with hot hide glue.

A couple hours later the sheets were finished and ready for mounting on another piece of baltic birch plywood. They were sandwiched between a Roubo-esque press and a handful of clamps for a couple hours.

After taking them out of the press and lightly dampened the paper backing was easily peeled off, leaving the panels festooned with the new design.

The trimming out and finishing of these panels was left to the attendees to complete once they got back home. Our emphasis was the layout and creating the patterns.

The second exercise began Saturday around mid-day. It was more complex in that it required a much shallower sawing and planing angle, and each pattern required the use of three species of wood.

For this we needed a sawing/planing jig set at 30 degrees rather than 60, in order to cut the triangles rather than the equilateral parallelograms of the first exercise. This image is of my own jig, which includes both the 60-degree and 30-degree setups.

Next post we’ll follow exercises #2 and #3 as they progressed.

One of the most fun aspects of the recent successful workbench-building workshop was that the group was small and the strategy for building allowed everyone to make their own version. I will present each of these as they come on line.

Bill wanted a small bench, perhaps only 52 inches long. Though we started out with 96-inch core slabs, we cut Bill’s into two pieces with the larger one being a petite Roubo to serve as the platform for his exquisite Emmert K-2 patternmaker’s vise. Over the years he had become enamored with my K-1, so when he saw this one at a yard sale he jumped at the chance.

After getting his benches home in their knocked-down configuration he slithered them into his basement workshop and got to work in outfitting the bench with his vise. Using his other bench made from the cut-off of the 8-foot slab core, which we dubbed “Bill’s Hobbit-Sized Roubo” or quite naturally “The Bill-bo” he set about excavating the void for the massive Emmert undercarriage.

He got that done and attached the vise’s base to the bench, and is currently cleaning up the jaw and screw for imminent re-unification.

I see he still has some trimming to do on the ends but as of now the bench is ready to get to work.

Still, I can’t wait to see the end of the tale of the Bill-bo…

In my preparations for the workshop this weekend I decided to switch two heavy workbenches, moving the 8-foot Nicholson from my studio over to the classroom (shown here in its new location in the lower left of the frame), swapping it for the 5-foot Roubo in the latter.

Since the lighter of these was over 200 pounds and I was doing all the work by myself I turned to my trusty sofa sliders from the hardware store. Slipping them under the feet allowed me to push the benches across the barn to their new locations with very little effort.

On the other hand the new location for the Nicholson is a little problematic in that the wood floor is a bit slick there, and with a very little effort working at the bench it would start scooting across the floor. So I needed to quickly make some non-skid slippers.

I started with two sheets of 80-grit emory cloth, and tore them in half.

I sprayed the back sides with adhesive, then folded them together so that each face was the abrasive side.

Then I slid a folded pad under each foot, and the problem of the sliding workbench was cured. Two sheets of sandpaper, spray adhesive, 90 seconds. Done.

I’m spending a couple of days away from my own projects in the studio and preparing the classroom for the upcoming parquetry workshop this coming Friday-Sunday (still one space available for anyone who wants to come to Shangri-La during some magnificent weather – upper 70s by day, upper 50s by night).

It’s going to be a lot of fun, in part because the structure of the event is different than I have pursued before. In most workshops, even those that are techniques-based, the structure is to present a narrowly defined set of exercises with the goal of accomplishing a specific project. The project can be large or small, but getting “finished” is dialed in to the equation.

My objective this time is much different in that we will be engaging in practices to learn techniques such that the participants can integrate them into their own work once they get back home. We may or may not get to “finished” but we will definitely get to the “I have mastered this technique” point.

Parquetry is all about precision sawing and trimming so much time will be spend deriving and constructing sawing and planing jigs.

The basic tool menu is preposterously small; take a block plane, a fine back saw, a 3-60-90 plastic triangle, and a compass or divider, add a little glue and you are ready to hit the ground with classical parquetry.

I got done with my latest article for Popular Woodworking. It’s all about one-handed binding clamps that are not only ridiculously easy to make but useful in a thousand ways in the furniture making or restoration studio.

I cannot recall in which issue it will appear.

Stay tuned.

For the next few weeks I will be spending portions of my time getting ready for our near arctic winters. That means cutting firewood literally by the ton.

The other day my pal Bob came by to spend an hour or two getting trees down on the ground. Bob has many skill sets in life and one of them emerged from his years as a timberman in his youth. Together we got about a dozen trees down, most of them dead or dying locust trees whose firewood I prize. When I say “we” I mean Bob, with me mostly just standing out the the way. I am not yet confident in my ability to get a large tree down safely every time, and for Bob it is just second nature. Once they are on the ground I have no trouble chopping them up with my slightly smaller chain saw.

To the southwest of the barn I am trying to thin the trees in order to get better winter sun. Given the stand of trees there now I lose the sun by about 3PM in December and January, so If I can move the tree line back a hundred yards it should get better. But that is another five or ten years worth of firewood.

So over the next month I will be closing out the days with at least a couple of hours of chopping, splitting, and stacking firewood until I have garnered about 25 cubic yards to augment our half-winter’s worth of firewood left over from last year.

Stay tuned.

Recent Comments