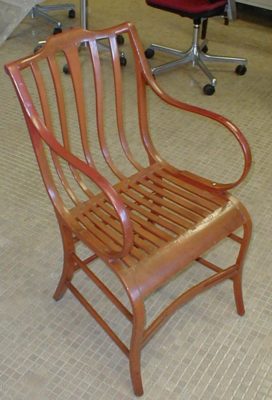

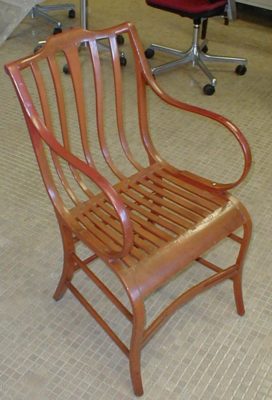

2023 is shaping up as a pretty Graggtastic year in the shop. I am in the home stretch of the copious pinstriping for one chair to be delivered. A second client’s chair is fabricated but I have not yet begun the painting, and a third chair is about half built.

Then last week I was contacted by someone who has a Gragg chair with a broken arm, and based on the images they sent it just *might* be ONLY THE THIRD ORIGINAL, COMPLETE ELASTIC ARM CHAIR known to exist!

There is the completely overpainted chair at the SI that I kept in my conservation lab for almost two decades, trying unsuccessfully to persuade the curator to allow me to remove the overpaint.

Then there is the beauty at the Carnegie in Pittsburgh, and the heavily restored one in Baltimore. Unfortunately at the moment I cannot find my overall photos of the BMA chair but I have a large folder of detail shots. As I understand it the Baltimore chair was missing some elements that were newly fabricated and integrated to make a whole chair.

This newest chair has a tricky repair to be made to the arm, and the putative client inquired about me making a new chair to make a pair with the old one.

On top of all of this excitement there are several new Gragg-ish projects on the drawing board. Without revealing all the cards, consider that 1) we have a new grandson, and 2) the front porch of our Shangri-la cabin is rocking-chair-tastic.

Finally, I’m at long last seeing the light at the end of the tunnel for the “Build A Gragg Chair” video set. Whether that light is sunshine or an oncoming train I cannot yet be certain, but I remain hopeful. At the moment I am estimating the series to be more than a dozen half-hour-ish episodes, and Webmeister Tim and I are noodling the mechanism for the on-line offering. I’ve had one faithful donor sending me a small contribution every month (THANK YOU JimF!), but we need to come up with a system for processing the $1.99(?)/episode charge without viewers crawling up my back as the episodes are released. One approach I will almost certainly NOT take is a subscription model. I’ve spoken to some subscription-based content creators and they are unanimous in their regret. No matter how much content they create, their subscribers want more, and more often. I want no part of that.

Now the only thing left in the equation is the resolution to the question, “Why am I not as energetic and productive in my 68th year as I was in my 28th?”

‘Tis a mystery. Who knows, if I can solve that problem, I may even want to offer another Gragg chair workshop if there is interest.

After much noodlin’ and experimenting I wound up in the place of resolving the problematic silica flatting agent deposits in the interstices of the antique wood of Mrs. Barn’s clothes cupboard doors. Unfortunately the destination was a place I did not necessarily want to go — picking out all the offending material with dental tools.

A few hours of work (I did not keep track as I popped in and out on the process) was all it took to get things back to a good place from which to proceed.

I really did not mind, for most of the past forty years I became accustomed to delicate, tiny-scale work, frequently under a stereomicroscope. I guess if you find such work intolerably tedious, art conservation is not a good career path for you. At least in this case I was not tethered to one of my microscopes, reading glasses and good directional lighting were all I needed.

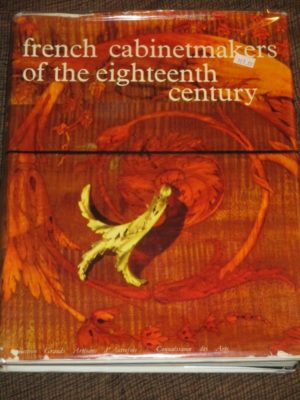

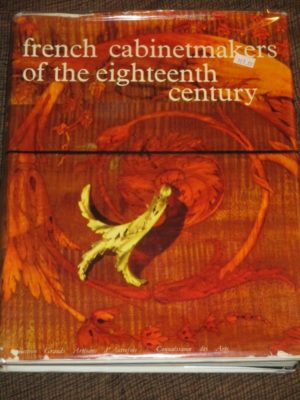

One project from the past came to mind as I was picking out all the bits of crumbly whitened varnish. It was a late 19th Century Alexander Roux cabinet that had been gifted to the Institution, needing a fair bit of work. The original base had rotted off due to the cabinet sitting on the mud floor of a basement, so it needed a new base along with all the bronze mounts. I sculpted the wax patterns for the new mounts and cast the bronze myself.

But, the most nettlesome aspect of the project was the intractable accretion of untold layers of linseed oil-containing furniture polish on top of all the surfaces including the patinated copper and bronze on a large cameo medallion that was the visual centerpiece of the cabinet (the main purpose of the cabinet was to hold either one piece of sculpture or a flower arrangement on the center of the top). Over the years the linseed oil had hardened into something akin to Scotty’s transparent aluminum due to imbibing metal from the substrate leaving an encasing residue essentially un-removable by ordinary means. The only effective technique was to formulate and slather an ultra-high pH Laponite gel, which coincidently removed the patination on the underlying substrate. That was not a desired outcome.

Eventually I wound up fabricating some ivory scrapers to chip off the deposit, working entirely underneath a microscope to protect the undulating surfaces of gilded bronze and patinated copper. The ivory scrapers looked like dental tools and were used because they would chip off the rock-hard contaminate yet not scratch the substrate. In the end I was exceedingly pleased with the outcome.

But back to Mrs. Barn’s cabinet doors. After removing all the deposits with the dental tools and scouring the surface with a wire brush, it was time to try applying a new coat of gloss oil resin varnish.

Whew. I can now proceed to completion, building up the finish to a matte presentation.

My perfume-infused book has been in the deodorizing chamber for a month, but my on-board stench-o-meter is not calibrated to detect any change in the level of noxiousness. That change will occur given enough time, as the offending molecules are adsorbed into the charcoal medium.

The effectiveness of the protocol has been demonstrated for me numerous times, most recently inside the cab of my new-to-me pickup truck. On the long drive home from the DC-area dealer I noticed the faint but definite residual odor of tobacco smoke in the truck, which had I noticed it earlier it would have been a deal breaker for me. Anyway, as soon as I got home I bought four bags of lump barbecue charcoal and set them in the back seat of the truck for the past four months. Slowly but surely the charcoal gently removed the stench from the space. Last week Mrs. Barn and I journeyed over the mountain with nary a whiff of the detestable odor. So, I have every confidence that the book will emerge relatively un-pungent at some point. What I do not know is exactly when “at some point” will occur.

But back to the book itself. While the book has been inside its deodorizing chamber I was noodling another copy of it on-line. Much to my astonishment a copy of the book in nearly pristine condition for a mere fraction of the expected price. It was an important lesson for me, namely that sometimes a hard-to-find book turns up on ebay.com for sale by someone who does not really have a working knowledge of the value. $17.50, shipping included (it is a ten-pound book).

The outcome is a near perfect circumstance; I get to enjoy the book while undertaking an odor-scrubbing exercise in real time.

I think I am more or less back on track, compewder-wise. I took some advice from RalphB and placed a sledge hammer next to the keyboard and spoke to the compewder in calm but undeniably threatening terms. It has been behaving better ever since. Actually, compewder guru Tim had a session with it. — DCW

As we left the (mis)-adventure with the batch of Mel’s Wax having identified and solved the problem, I was left with a large batch of the misbehaving product to deal with. Of course my question was, “Can I recover this and make it useful?”

I first let the emulsions sit for a week or so then decanted off the excess solvent from the top of the jars with a pipette. The result was a couple of paper cups filled with nearly pure solvent which I merely disposed of as it was of no use to me. I was careful to not dip the pipette too far down into the liquid so as to leave the emulsion itself untouched. This cautious approach left a small amount of excess solvent fraction stratum on top of the liquid.

I decided to remove this excess fraction using techniques familiar with anyone who has ever undertaken some liquid chromatography, I simply wicked off the surface excess by draping in a strip of paper towel on top.

The ultimate result of this approach was to arrive at the balanced formulation with the emulsion performing and behaving exactly a it as supposed to behave and perform. Nevertheless this was not product I was going to sell given the log and winding road, so I now have couple dozen jars I will give away to friends and barn visitors.

Thanks to a recommendation from my friend Steve Voigt I will be trying a new source for the solvent and will re-calibrate the formulation for future batches.

NB – This is not only my 1,500th(!) blog post over the past 8+ years, it is the longest one I’ve ever written. By far. Normally a post takes me from 30-90 minutes to create, occasionally longer or shorter. For this one, depending on your timekeeping system it took me a) four weeks, b) four months, c) four years, or d) four decades. So which one was it?

The correct answer is, “Yes.”

In order to tell this tale with some completeness I need to give you a tiny bit of background context. (In truth it turned out to be something more than a “tiny bit” but it is far less than a proper detailed exposition. I think that would be too much for 99.8% of you, and since I have about 300 readers that pretty much eliminates everybody — DCW)

To determine the cause of the soup-iness of the batch of Mel’s Wax, it should be the viscosity of a lotion and was instead the viscosity of heavy cream, I needed to go back to the beginning to reflect on the original concept for the formulation. This will be long and winding tale but provides the fullest possible explanation I am able to share about the reason for the batch “failure” (as I said earlier it was not really a failure, it was just not the precise outcome I had expected. In the end it turned out just fine.) I should probably break it up into three or four posts, but I decided to just put in one big steak rather than several smaller burgers. So, settle in with a snack and your preferred beverage for this ride. I don’t think you necessarily need to buckle up, but if a discussion of solvent thermodynamics gets you all worked up into a rave perhaps you need to restrain yourself as well.

BTW This post borrows heavily from the section that has been the bane for the past year of writing A Period Finisher’s Manual. And yes I have finally solved that particular puzzle and am back at work on APFM almost daily. Yup, it has taken me over a year to get a handle on one part of one chapter. Were it not so important to the craft of wood finishing I would not have bothered, but it is and I did.

From the beginning of our careers, even before we met and worked together, Mel and I formulated and mixed our own furniture maintenance polishes because we were not content with the products in the market. The commercially available products often used ingredients we knew a priori to be potentially deleterious to historic finishes, or used ingredients in proportions we thought were not optimal (for the furniture), or were simply too difficult to use.

So, the product Mel finally derived (I withdrew from direct participation fairly early for logistical reasons once we knew the development was on the right track; the easiest way for the project to move forward was for me as Mel’s Supervisor to assign him the task of taking it to fruition with me providing oversight and the occasional observation, review, or suggestion. Participating directly, as a Supervisor and programmatic manager [read: fiduciary] would have been an administrative nightmare) fulfilled splendidly our goals for “the ultimate furniture polish.” I do not believe it to overstate the case when I note that from a formulary’s perspective, it was balancing along a knife’s edge. That balance was lost minutely in mixing this batch of the polish, but that is all it took.

Here were the original goals, which Mel fulfilled brilliantly and deserves all of the credit and the Patents* that were issued.

- The end product was archivally stable.

- The product was chemically benign regarding historic finishes.

- The product was physically benign regarding historic finishes; the product was easy to apply and bring to a high sheen.

- The product was very high performance for both the presentation of the object and its ongoing maintenance.

- The product was easily removed with no damage to the surface from the removal process.

- The production of the polish did not require exotic technology

- The product was safe for the user.

These features are not independent variables per se, no component of any formulation or application is separated from the others, but they are different conceptually and thus I will provide exposition on each one.

Archivally Stable

“Archival” is at best a vague word without objective quantifiable meaning, but for the sake of this discussion simply use it to mean that some material or composition of materials does not degrade unacceptably fast and that any degradation by-products do not become manifest as pernicious actors in the realm of deterioration. That does not mean the word/concept has no utility when formulating a composition or even a practice. For Mel’s Wax the ingredients and their proportions/mixing were chosen with great care, and selected for long-term stability. This has pretty profound influence on the making and shelf-life of the product. Though the primary ingredients of Mel’s Wax (the waxes themselves) have a half-life that is near-infinite within the context of recorded human history, others were selected for the longest possible half-life, such as the exotic emulsifiers. And, the ingredients were selected with essentially zero cost consideration. Think about an old favorite like Murphy’s Oil Soap, which retails for a few dollars a quart. The emulsifiers used in Mel’s Wax, again, selected because of their stability vis-a-vie their degradation curve and chemical neutrality (see below) wholesales for *hundreds of dollars a liter.*

Chemically Benign to Historic Finishes

One of the truths of this particular cosmos is that the Law of Entropy cannot be repealed by even the most highly self-esteemed persons. “Ashes to ashes dust to dust” is not merely funereal homily, it is an inexorable reality in a cosmos governed by the laws of thermodynamics. So, as furniture finishes age they become closer to the “dirt” aspect of the verbiage just cited. As a practical matter this means that historic surfaces and finishes become more chemically imbalanced over time (usually due to UV damage or the imbibing of oxygen) and thus more susceptible to chemicals that impart damage because the chemicals deposited on the surfaces are thermodynamically similar to the surface and will thus impart undue harm to the said surface. This means that we have to maintain as close to a neutral balance or “polarity” for the chemical concoction being deposited on that surface. This, in turn, affects the choice of ingredients to be the most benign possible, which in turn influences the procedures for making Mel’s Wax. Those crazy expensive emulsifiers I mentioned earlier were selected specifically because they are less aggressive in creating the lotion-like polish, and thus less likely to inflict harm on chemically fragile surface. Further, the proportion of the emulsifiers in precisely calculated since excess emulsifier is a vector for accelerated chemical reactions, a/k/a “deterioration.” Also, the selection of the organic solvents used in creating the oil-and-water emulsion were selected for the maximum benign characteristics for aged surfaces.

Physically Benign to Historic Surfaces

There are some fine archival and chemically neutral furniture care polishes on the market in the form of paste waxes. Unfortunately many of these products require sometimes aggressive rubbing of the surface to bring their applications to a conclusion. Whenever you are faced with a physically delicate surface the last thing in the world you want to do is rub it hard to burnish the maintenance coating (paste wax). Given that reality based on what we knew it was pretty apparent that Mel’s Wax would need to be a creamy emulsion requiring very little physical impact on the surface for either application or completion.

High Performance

“High performance” is just another way of saying “It is physically robust and looks good.” It is and it does.

Easily Removable

For long term preservation and care considerations any museum artifact maintenance product must be removable with the minimal physical or chemical impact on the sometimes fragile underlying surface. Mel’s Wax was designed precisely to be removable with non-polar solvents and soft wipes like cotton swabs or lint-free felt.

Easily Produced

This was the point that precluded commercial-scale productions. It is very fussy to make, in fact my experience is that it would be difficult to make in anything larger than a five-gallon batch; I normally make Mel’s Wax just over a gallon at a time. The ingredients must be mixed precisely and with a fairly strict time frame. Further, the thermal ramping (the rate of heating up and cooling down) is a real stinker. Commercial enterprises, used to making home-care products in vats of several hundred gallons at a time, could simply not get it right. Many companies tried, including some you might recognize; they all failed. Instead the protocol Mel derived was a fussy micro-batch process that can go south with just a fraction of a percent of deviation. In that regard it failed the “easy to produce” goal.

Safe to Use

Not incidental to the formulation design is that the end product would not only be benign for the artifact, it would be (comparatively) benign for the user. Yes Mel’s Wax does contain organic solvents that are by definition deleterious to human consumption, but they are not acutely toxic compared to the overall landscape of industrial chemical engineering and formulation. Eating or drinking it would end you up in the emergency room rather than the morgue. As Dixie Lee Ray articulated in the Foreword to her brilliant book Trashing The Planet, under many situations di-hydrogen monoxide (water) is a lethal chemical. Like, for example, if you were to experience extended, intimate and excusive exposure for more than a couple minutes, e.g. unmitigated complete submersion. That would be a fatal incident.

Back to “The Cause”

This, my friends, is here the adventurous rabbit trail of solvent thermodynamics comes into play. As I mentioned earlier the formulation for Mels Wax was a razor’s-edge situation; if any component of the manufacturing was off by just a smidge, whether ingredient, proportion or process, the delicate balance of the formulation would be undone, or at least modified from where it was supposed to end up.

And that is what happened, but not in the way I was expecting. Solving the problem was an energizing exercise in synthetic thinking, combining the phenomenon (that which can be observed) with the noumenon (that which can be imagined).

When I was making this batch I was relying on my old faithful solvent, odorless mineral spirits, from the hardware store. There is nothing wrong with generic or even common ingredients like this provided they are the same thing from the manufacturer every time. I’d had great success with this particular solvent over the years. However, this time when I opened the container and decanted the necessary amount of the solvent into the weighing vessel (the formula is designed to assemble the ingredients by weight, not volume) the solvent coming out of the container was the consistency of chunky sour milk (fortunately it was odorless). Clearly some “shelf life” issue of the solvent and its plastic container was at work here. I tossed all of that and cleaned up to move on to the next gallon jug. Same thing. Repeat and rinse. Same thing. And with that I was out of my trusty tried and true odorless mineral spirits.

No big deal, I just picked up some new solvent, from the same company to (supposedly) the same manufacturing specs, and proceeded as normal. The solvent looked fine, the procedure went smoothly and I set about with other tasks until the polish gelled to the expected creamy lotion viscosity.

I came back in an hour and the polish had not gelled. No reason for hysteria, it as a very warm day and the thermal ramping was just being petulant. I came back in the morning and the gelling was still not to my satisfaction. Hmm, what was going on here? I even refrigerated one jar and it did not thicken to the desired viscosity.

At this point I stepped back from the entire episode for two weeks, just letting the stuff sit on the benchtop of the Waxerie while I cogitated. After those fourteen days I revisited the batch of the polish and noticed something peculiar — there was a stratum of pure solvent at the top of every jar. In a moment I knew what had happened.

The Crystal Set/Key-and-Lock Analogies – The Solubility Parameter

Have you ever wondered why substance A will dissolve in solvent X but not solvent Z? That question is perhaps one of the very most important questions in coatings technology and you would be wise to contemplate it. There is a real answer and I am going to tell it to you in a roundabout fashion. Hey, it’s my blog and I can tell the story any way I want. Hint -it all has to do with interatomic/intermolecular energy matching.

Stick with me now.

When I was a kid I got a crystal set radio, an earth-powered (actually it was the charge from the earth through the grounded radio chassis that made it work) primitive AM radio that allowed me to get the closest radio station to the house. I would spend many evenings listening to that local radio station, and after dark when the locals went off the air I could tune in the station from the next town over. Even though the crystal set had no power source I could listen to broadcast radio. Why? because the crystal of the crystal set allowed the unit to align, or match (receive), the frequency of the signal being broadcast with power being derived from the ground (I am not a radio engineer and did not stay in a Holiday Inn, so cut me some slack. I’m trying to explain a concept, not enter the debate about Marconi vs Tesla vs. Edison). Even with only the nearly unmeasurable electrons flowing through the crystal set it could “dissolve” the radio signals being broadcast because they were matched to each other.

Let me try another analogy.

Assume you come to visit me and my barn is locked (the punch line of my all time favorite joke is, “Assume a can opener.”). Not to worry, you’ve got the biggest honkin’ key known to man in your pocket and you go after the lock on my door. (I am assuming this action is done with my permission or you would have likely suffered a less beneficial outcome). Is this going to work, are you going to get in? Probably not. Why? Because the configuration (the energy) of the key does not match the configuration (the energy) of the tumblers in the lock.

And that my friends is why the polish was soupy. Let me explain.

The “solubility parameter” is the aggregate of (at least) three fractional components, which are in turn very specific intermolecular energy values. We use a graphical tool called the Teas Diagram to visually plot out the dissolving characteristics of both solvents and solutes, although this is an incomplete tool for selecting ingredients in a finish formulation. I discuss this at some length in A Period Finisher’s Manual.

The formula for Mel’s Wax depends on an organic solvent blend of a particular energy balance or “polarity” in order to walk the razor’s edge and fulfill all the preferences described above. To work perfectly the energy holding the solvent blend together (the key) had to match the energy holding the ingredients together (the lock) precisely — not perfectly — in order to accomplish the end point we wanted. My old dominant solvent had the exact correct energies to match the ingredients were were putting into solution in this particular operation. This phenomenon is called the “solubility parameter” as it is literally the aggregation of the interatomic and intermolecular electrical forces holding everything together, at least in the universe of solutes and solvents. Often it is reduce to the verbal shorthand of “like dissolves like.”

Yes, there are solvents for Mel’s Wax that could do the dissolving more efficiently than others. Solvent/solute compatibility is a range not a fixed point since no solute or solvent is 100% a pure single molecular content, and within one particular range we got the desired outcome. Was this solvent blend the “perfect” one to create the solution? No, because perfect solvation was not the preferred outcome since that “perfect” solvent blend would not fulfill the previously stated goals. For that we needed a milder (less polar) solvent blend. As I said the solubility parameter allows for a range of options to accomplish similar goals and characteristics.

Getting back to the original issue, why was this batch of polish soupy? Because even though the new solvent as ostensibly identical or similar to the previous solvent (it was similar but not identical) and still well within the “safe” range or creating our archival polish, it was just enough different as to perform more efficiently as a solvent. In short, each unit of solvent dissolved more of the polish ingredients than the previous solvent, so less of the new solvent was needed to accomplish the task of doing the dissolving. In a normal solvent/solute solution this is usually no big deal, the solution is just a tiny bit more diluted than would otherwise be expected. But, in a two phase system like an emulsion combining an oily fraction with a watery fraction even minute deviations can impart huge differences.

In the end, the polish was soupy because there was excess solvent that had nothing to do but sit around and be liquid adjacent to the two phase emulsion. Yes I could force it to go into the emulsion but it would not stay there. As I showed last time the performance of the polish was unaffected. It was just soupy, that’s all.

But I didn’t want soupy so stay tuned for the next episode of As The Polish Turns to see how I responded to the problem.

Recently I had some time to spend working on a pair of early 18th Century Italian friends near Mordor. As is almost always the case with wooden objects veneered with tortoiseshell, the delamination problem is never really solved as the wooden substrate and the mostly thermoset protein polymer veneer react to moisture changes at different rates. In this particular case that problem has been exacerbated in the distant past by the traditional housekeeping practice of slathering tortoiseshell with olive oil and linseed oil. The practice is deleterious is every way, especially over time.

This time there were two sections of tortoiseshell that had become fully detached like this one, they were reattached with 192 g.w.s. hot animal hide glue after cleaning the substrate.

Then I worked my way around the mirror frames and identified a dozen places with delamination but not detachment and laid these back down after working glue underneath.

In the end I cleaned up the surfaces and applied a thin layer of Mel’s Wax over the surface.

I also documented the two dozen small losses on the frames; these are not detrimental per se and the client may want me to address these losses at some point in the future.

For now they are back up on the wall doing what they are supposed to do – look beautiful. I no longer accept new clients, but expect to care for these old friends as long as I am abe.

Normally at this point of the formulation the molten polish is an almost transparent amber liquid. It usually does not obtain this white-ish opacity until after it has been transferred into the jars and cooled for an hour or so, a little longer on a warm summer day.

With a recent batch of Mel’s Wax behaving oddly, becoming white-ish much earlier in the process than I have come to expect but nevertheless attaining the expected appearance when fully cooled. This batch remained almost fully liquid when it should have congealed into a soft lotion, and I set it aside for several days to cogitate over the cause(s).

Just to make sure I was not completely misguided I tested a bit of this liquid polish to judge its performance, and it did just just fine. So I did a contemplation deep dive to consider what might have “gone wrong.” In retrospect “gone wrong” was not the correct perspective, it had just developed differently than previous batches. But still, the question was “Why?” (A second question was, “Is this a new product?”)

When I returned to the jars after letting them sit undisturbed for a week I noticed an even more distinct stratification of the contents than had been suggested immediately after the making. In fact the top quarter inch of every jar was a near-pure fraction of solvent.

Using a disposable pipette I decanted the free solvent from the top of every jar, depositing the excess into a single large paper cup. According to my digital scale the contents in each jar included 20% excess solvent. Hmm.

Once the excess was removed the emulsion polish fraction underneath the solvent fraction was much more like the polish should be, and again performed precisely as it was supposed to. This observation made me reflect not only the original formulation from 15 years ago but also my materials used the previous week. It was a noumenological exercise, a/k/a “thought experiment,” that in the end bore great fruit.

Next time – The Cause.

The work of repairing D’s broken chair leg had the additional challenge of intact upholstery in place, and I had no desire nor skill to peel it all back to do the work. This is not the first time I have had a similar challenge of making a fundamental structural repair to a piece of seating furniture without the luxury of really intruding into the fabric of the object One notable example of this problem was a c.1800 painted shield-back chair with a very old hand woven cane seat and a snapped side rail. The client insisted that the repair leave both the painted surface and the hand-woven cane intact, yet restored so solidly that the chair could be used on a daily basis.

In the case of D’s chair I had to peel back the dust panel and just enough of the upholstery so that I could get access to the damaged area. That consisted of a blowed-up-real-good corner joint with snapped off dowels, blown out seat rail end, and everything under stress from both the upholstery itself and the underlying springs which were still affixed to the frame.

The front rail had been pretty busted up and the dowels damaged and even broken off. I made the first repair by reassembling the broken seat rail, using PVA and rubber bands as the clamping mechanism.

I gently drilled out the center of the broken dowel after first cutting it smooth with the joint face. After removing most of the mass with the smaller drill I cleaved off the remaining dowel mass with a small carving gouge until I got everything removed that I could do safely. Using the proper sized drill bit I “re-drilled” the dowel hole by hand. That made the reassembly pretty straightforward.

I also had to remove the corner brace completely, as it had broken loose and was not properly aligned even when the chair was new. After cleaning the gluing surfaces and placing it properly, once reglued and screwed it was mighty strong.

Reassembling the complete structure of the corner took a whole lot of clamps just to get things aligned, remember that the springs were still holding the deck together and exerted a lot of force making the configuration an issue. I carefully placed the upholstery back where it belonged, doing my best to overcome the puckering induced by the original structural damaged puling the fabric out of place.

It sat under a furniture pad until the D’s husband came to pick it up, and then it was on to the next project.

Recently I was asked by a fellow congregant to repair his wife’s favorite chair, a small upholstered piece (that might have been used as a trampoline by the grandkids). Regardless of the actual genesis of the damage, the front seat rail had its joint snapped off at the proper left end and pretty severe distortion was the result.

For a project like this I use an exceedingly cautious approach since I am not an upholsterer. Removing the dust panel from the underside of the frame revealed the extent of the damage. Wowser. The rail had blown apart at the joint, and one of the dowels had also snapped off. Repairing this was a good reminder of why I am trying to be retired from the biz.

My expert opinion based on almost 50 years of fixin’ furniture was, “Yup, it’s broke.” Both the dowel joinery between the rail and the leg and the concomitant glue block had busted loose so I set about getting it right.

Stay tuned.

A couple weeks ago while clearing out some stuff from my basement workshop at my daughter’s house, I came across an experiment that is almost forty years old.

In the world of historical fine art one of the premier positions is held by “panel paintings,” or fine paintings composed on a solid wooden panel. Given the age and prominence of these artworks, and the fact that they are unbalanced construction on an inherently unstable base given the presence of a precisely constructed laminar gesso and paint layer on the front side of the solid wood panel, caring for these artworks takes a high place in the preservation hierarchy. Very early in my museum career I found this problem to be a fascinating one, and the data points of my career projects (when I was able to choose the projects to work on, which was most of the time) revealed that it was the quality of the problem that motivated me much of the time, not necessarily the notoriety of the artwork/furniture. That explains my final project, which was the stabilization of a pair of wooden flag poles that encompassed a peculiar approach to addressing the problem of split timbers.

Back to panel paintings.

(Photo by H.L. Stokes via Wikipedia)

To counteract the unbalanced construction on a dynamic foundation, many, perhaps even most, ancient panel paintings have been augmented with a framework applied to the back side to both balance out the construction somewhat, but also to mitigate the tendency of the wood panel to warp. Sometimes these added features, called “cradles,” are elegantly sophisticated. Others are sophisticated and deleterious to the panel as the “floating” spines bind in the “pass through” blocks that are glued to the back side of the panel, inflicting new fractures to the panel along with the distortions as the panel attempts to expand and contract while the bound spines hold it in fixed dimensions, essentially a fixed cross-grain construction. This problematic outcome caused the entire concept to be reexamined beginning about the time I was coming into the museum world and many panel paintings have been de-cradled.

Shortly after hearing a seminar presentation on the topic in 1982 I decided to construct a prototype integrating my understanding of what wood is and how it behaves with some out-of-the-box thinking. Given that many of the old cradles were actually damaging the panel paintings, clearly a different approach was needed. Believe me, the number of alternatives to traditional cradling were legion, and even the last panel paintings conference I attended included several novel and unrelated options.

So I made a full scale model to test some ideas I had rattling around my brain pan. For starters I selected a less than premier piece of wood, it was literally a 2 x 12 resawn, planed, and glued together with hot hide glue into a “panel” approximately 20″ x 30″.

I then fabricated a series of “pass through” blocks with rounded contact points for the floating spines, which were themselves fairly lightweight, with the entire system glued to the back side of the panel.

You can see the construction of the blocks from this one that had been broken somewhere along the line. I applied spray dry Teflon to both the rounded faces of the blocks and the floating spines, hoping that the shape and permanent dry lubrication would prevent the blocks and spines from binding together (Teflon being the slipperiest substance on earth).

After assembling the entire model and showing it to the paintings conservators at the museum (I was working at Winterthur Museum at the time) I set it aside and literally forgot about it for almost four decades. Presumably it has been just sitting in the basement for all those years, responding to changes in the unregulated environment of the space. Over the life of the panel there have been swings in humidity from 100% to maybe 25%, more than enough to impart hysteresis cycles a’plenty.

Much to my delight the assemblage has suffered no ill effects over the decades, so at least the concept proved sound. The original construction is still perfectly flat and there are no instances of long-grain fracture to the wood. Admittedly the panel is balanced in that both faces are raw wood open to the microclimate so there was very little impetus for severe warpage. Still, I would have expected some loss in planarity if there was a flaw in the concept. Nope, still dead flat.

Now that I have reclaimed the experiment I will create a simple paint scheme on the face to mimic the structure of a typical Renaissance panel painting and see how the experimental cradled panel responds over the years. I will leave it sitting out of the way in the barn essentially exposed to the elements except for rain. I’ll check back with it in, say, another 38 years to see how it did. I’ll be 103 then, but I just got back from celebrating my Mom’s 103rd so that might not be too crazy.

If it still looks good then I’ll let someone in the museum world know about it.

Recent Comments