I spent a day steam bending the conditioned dry wood with very instructive results. Not success, per se, but definitely instructive about the pathway to success.

I’ll backtrack to review the protocols for conditioning the dry wood.

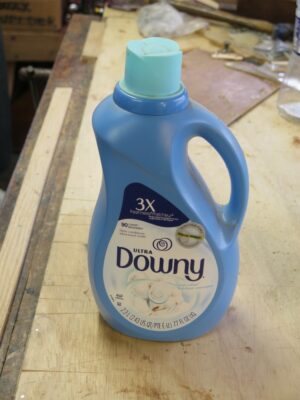

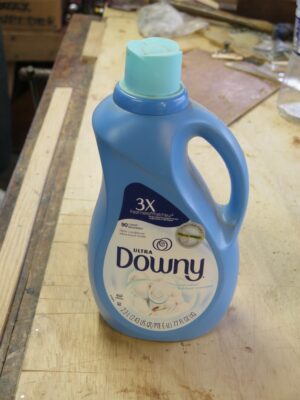

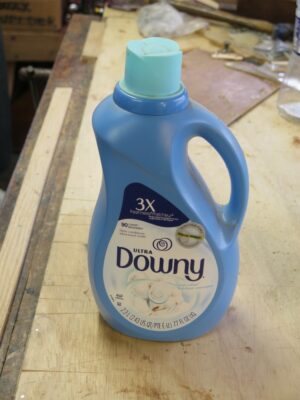

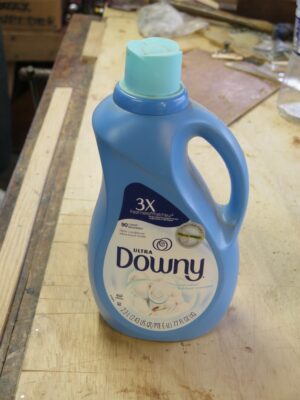

Using some PVC from the stash I made three 40-inch-long tubes into which I placed two serpentine pieces, two arm pieces, two uni-splats, and two rear legs from the mini-Gragg. In the first one I created a 1% surfactant solution with distilled water, in the second a 1% ethanol solution with distilled water, and the third was a 1% fabric softener solution with distilled water. All pieces were fully submerged for the duration.

I let these sit for seven days and fired up the steamer.

To accentuate any effect of the conditioning I steamed the pieces for 1-1/2 times longer than might be expected for steaming green-ish wood, then bent them as quickly as possible. This meant 30 seconds of intensity after 35 minutes of steaming for the thinner components, and 75 minutes for the rear legs.

The results were instructive but not particularly encouraging for the extremely bent pieces, namely the arms and serpentines. That said I could definitely feel a differences, it just wasn’t enough for complete success.

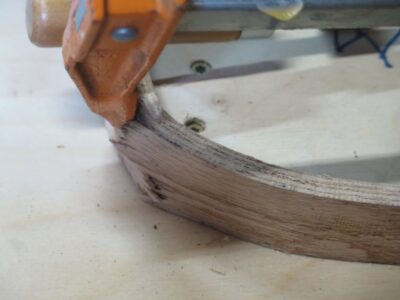

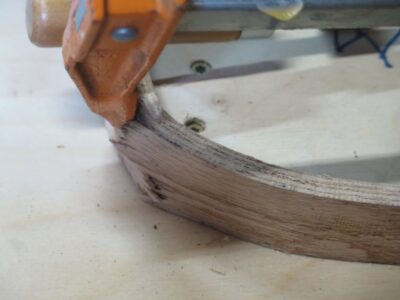

Somehow, I missed this excessive run-out on the side when I was toothing the faces. This piece was never a good candidate under any circumstances.

In each protocol the uni-splats worked almost perfectly, with the only failure being due to a wood grain flaw that I somehow missed during the preparations.

This bend was “this close” to making a successful bend, but at the final instant let loose with enough tension to break. It is possible that this piece could be salvaged with epoxy impregnation.

This one busted right away…

… while this one flat out ‘sploded.

In bending the twelve extreme pieces – 6 arms, 6 serpentines – the failure rate was 100%. The pieces felt very plastic, bending nicely until an instantaneous catastrophic failure. It was abundantly clear that the fabric softener worked the best of all the conditioning approaches.

I did have one instance of compression buckling. Why this one? I got no idea.

The takeaways were indisputable and I will tinker with these further. 1) use fabric softener to condition the wood, and 2) the serpentine and arm configurations cannot be accomplished without compression straps. For the full-size Graggs I have used plumbers straps screwed to the bending stock but for these I will make compression straps from aluminum flashing, then tack them with aluminum tacks to the stock prior to inserting the pieces into the steamer. That way when the wood is cooked I can remove them and bend them instantly. The reason I am taking this approach is that I need for the compression straps to be exactly the width of the bent element and plumbers straps are narrower than the components. And, I do not need to keep the surfaces of the bent elements pristine since they will be painted once the chair is assembled and thus any tack holes will be filled with primer.

Stay tuned as I dive in again.

I took a 10-foot piece of 3-inch PVC pipe and cut it into three 40″ pieces and glued on end caps to use as my re-conditioning chambers for the dried wood in preparation for steam bending it. I filled each of the three with “modified” distilled water.

In the first case I added 1% Everclear 151, if you recall I have a lot laying around, to do nothing more than reduce the surface tension of the water and induce greater and quicker penetration.

For the second tube I added 1% of a mild detergent to act as a surfactant. I would have used some Kodak Photo-Flow, an artifact from ancient days when photography was a film-based process rather than the electron aggregation it is now. I could not find my bottle of Photo Flow (ordering more now) so I added some mild soy-based detergent, fairly neutral in its properties. Were I being anal retentive I would have used Triton-100 pH neutral detergent but I don’t have all that much of it left and it is pricey. Like the ethanol the purpose of the detergent is to act as a surfactant “wetting” agent and induce greater and quicker penetration of the water.

The final tube of distilled water was enhanced by 1% Downy fabric softener, to impart lubricity to the wood fibers. I have to assume that the Downy has some portion of surfactant/detergent in it for the same purposes I am using, namely penetration and induced lubricity between the wood fibers.

I added one more of the modifications to this exercise, namely the increase of the wood surface area via a toothing plane. Using one of my toothing planes I worked the flat sides of the wood strips until they were completely toothed, thus doubling the surface area. Combining the expanded surface area with the surfactants in the modified water I can envision excellent penetration and wetting/re-conditioning.

I prepared a couple of each of the bent wood elements, serpentines, arms, and uni-splats, and stuck them into the tubes of wetter water. To make sure they were completely submerged on the top end I cut and stuffed pieces of hardware cloth into the ends then topped off the tubes. What I’m reading from the interwebz and private correspondence the pieces need to stay submerged for a week, so it’s looking like Friday morning will be Steam Bending Day.

I await the event with anticipation. Even if everything is a complete failure I will have learned something important. But, if everything is successful I will have the necessary parts in hand to begin L’il Gragg. Probably not in time to finish before L’il T’s birthday, alas.

Over my many years of teaching furniture conservation, essentially an amalgam of materials science and aesthetics with a dash of esoteric problem solving, I always emphasized my conception of Synthetic Thinking. By that I meant employing/combining, or synthesizing, both the observable physical effects of doing this-or-that, along with the unobservable — ideas, knowledge, speculations, hunches, theories — roaming around inside our heads. In bringing both to the problem we would be synthesizing the Phenomenon, that which can be observed, with the Noumenon, that which can only be contemplated. I am reminded of the opening lines to historian Paul Johnson’s monumental work Modern Times, a history of the 20th century. As Johnson remarked, as I recall but it’s been a number of years since I read the book, Hiroshima and Nagasaki proved that Einstein’s theories were no longer just theories.

For now I am in the “Noumenon” phase of addressing the problem of steam bending dried wood. The Phenomenon phase will come soon enough as I put those noumenon contemplations to the test in reality.

For starters, there is great doubt as to whether kiln dried wood can be re-moisturized exactly as the wood was before it got dried, or whether it can only be conditioned to mimic green-ish-ness for the purposes of bending the wood. I suppose the chemical thermodynamics of re-integrating water molecules into or in between the wood fiber molecules could be accomplished, as my late friend and colleague Mel Wachowiak used to comment, “With enough force you can pull the tail off a living cow.” For now all I am trying to imagine is mimicking the effects of that integration.

So, how do I best get water into the wood to make it “green” again? (This may be the only time I will ever utter any desire to make things “green.”) There are many considerations to test out, but the point is how do I, or can I even, get water back into the wood to affect its behavior under the conditions I want, i.e. steam bending dried wood?

Merely soaking the wood in water is a place to begin conceptually, but by itself I surmise this to be a low efficiency way to approach the problem. Example: when I was trying to ebonize some tulip poplar to see if I could use it as banding for my tool cabinet, I soaked some 1/4″ pieces of the wood in a bath of India ink. Since the ink was waterborne shellac with a carbon black colorant, I could discern the effectiveness of the penetration by simply sectioning the wood and see what happened. What happened was that two weeks’ soaking submerged in the bath yielded a penetration of less than 1/16″. Though the objective was entirely different then than now, the memory of that exercise makes me less optimistic about that approach for re-moisturizing wood as a precursor steam bending. True, moisture diffusion in tulip poplar is not the same as with oak, whose moisture transport is much more dynamic. Even the oaks are dramatically different in their moisture transport, with red oak being much more transparent to moisture transmission than white oak due to the comparatively open cell/fiber structure.

Even so I considered several ways to enhance the introduction of moisture and came up with a few ideas to test out.

Modifying the Water

What could happen if I could make the water into something better? How about if I —

Make water wetter?

If I could make water wetter, in other words to increase its capacity for infiltration into the wood, I just might have something. Well, the two methods I have at my disposal for making water wetter involve reduction the surface tension of the water, to make it wick or flow better into the substrate more aggressively than it would on its own. The two methods are to 1) add surfactant, and 2) add solvent. In the first case simply adding some detergent or soap would greatly reduce the surface tension of the water and let it soak in more deeply and more quickly. In the second, adding water miscible (compatible) solvent like ethanol or propanol would do the same thing.

Increase surface area for better penetration

Regardless of how the water is modified, it is, I think, an undeniable proposition that giving it a greater surface area in which it does its penetrating magic is a winner. The question is, how do I go about that? I could easily multiply the surface area by dragging the surface over a bandsaw blade but that simultaneously imparts a multitude of cross grain irregularities, which would serve as a focal point for fracture origination.

But, how about increasing the surface area with along-the-grain striations? Something as simple as quickly working the surface along the grain with a toothing plane would increase the surface area by some factor approximating 2X. I think I’m liking this noumenon.

Or, changing the chemistry/structure of the wood on hand – ammonia gas at pressure, surfactant/fabric softener lubricity

I do not have either a pressure/vacuum chamber adequate for the chair pieces, so that isn’t even something to really contemplate. Maybe some day, but not this day. Besides, I do not expect to ever possess gaseous ammonia. Because. Besides, when using ammonia to facilitate bending wood there could be a lengthy off-gassing period.

On the other hand I do have fabric softener in the shop. I cannot pretend to possess a full understanding of how that would work but the product’s main functionality is to “fluff” fibers through ionic interactions, but also, more importantly, penetrate into fiber bundles and impart lubricity. Sure, wood fibers are not identical to textile fibers but they just might be close enough to do the same trick.

Quote David Bowie

How about some p-p-p-pressure? Or its inverse? As I said earlier I do not possess a vacuum/pressure chamber to force the water in or suck the air out, resulting in the wood sucking the water in, while this is a definite winner it requires technology I do not possess.

Use bending straps

Bending straps are a routine part of the equation when I’m bending full-scale Gragg parts, generally somewhere in the neighborhood of 1-1/8″ x 5/8″ in cross section. Since the Gragg chairs are always painted I just screw plumbers’ straps in the necessary places and get going. But for the L’il Gragg the pieces are only 1″ x 3/8″, with a bending cross section only half as much. I really hope to bend these without straps but will use them if needed.

Exploit Thermodynamics

In its most basic and fundamental applications, thermodynamics is the study of energy (applied to some function) x time (that the energy in applied). At our level of work we can assume some general inverse relativity; more energy means less time, more time means less energy to accomplish the same task. This may or may not work here as there are activation energy thresholds. But what about changing the formula for steam bending from 1 hour per inch of wood to 2 hours, 3 hours, X number of hours? It might just work, but my steam generator only holds about 1-1/4 hours of water. If I take a lengthy trip down this theoretically sensible route, I would have to devise a whole new water heating/steam delivery system. That strikes these lazy bones as non-optimal.

Using different wood (harvest new trees)

It could be that in the end none of these options, individually or in concert, will do the trick. In that case, fire up the chain saw and reach for my bag of wedges and the froe. It’s about time to continue work on next winter’s firewood harvest so maybe that’s the route.

But not until I gather some phenomena.

With a momentary semblance of normalcy returning to Shangri-la I was able to get all of the stock planed and dimensioned for the L’il Gragg chair and get set up for a steam bending afternoon.

Bending jigs in place and secured? Check.

Steam box set up? Check.

Plenty of distilled water on hand from the Dollar General? Check.

Okay, let’s load up the steam box and get this stuff cooking!

Since the wood being used was not really “green” any more I gave it a little more cooking time, 40 minutes for the sticks instead of the typical 30 minutes as would be appropriate for the <1/2″ oak.

The first piece was almost fully bent when I heard the dispiriting cr-r-r-a-a-a-ck. Okay, let me give it ten more minutes in the steam box and try it again. Same cr-r-r-a-a-ack. Ten more minutes. Same result. Ten more minutes. Same result. Ten more minutes. Same result.

By this time I had a complete pile of broken parts. All of them broke. All twelve of them. A 100% failure rate. Had there been a microphone inside my head the sounds would have peeled paint.

What went wrong? The wood was all harvested by me, by hand, from a newly felled tree. The problem is that harvesting was a dozen years ago. Some of that stock I’ve kept stacked in the basement of the barn and had worked it just fine as recently as 18 months ago. Unfortunately, as I dove into Lake Gragg again a few years ago I moved a lot of the pieces up to the attic of the barn for future use.

It’s an old image but gives you the scale of the asphalt roof

Given the location of the workspace, directly underneath the asphalt paneled roof, it gets mighty hot up there in the summers.

I am surmising that I now have, in effect, a large stock of kiln dried chair pieces. Even though the material was almost green air-dried wood when I brought it up, several summers worth of scorching heat in the attic resulted in bins full of transformed wood, with both the inter- and intra- molecular moisture having been driven out.

Now the task is to noodle the reconditioning of kiln dried wood for the purposes of steam bending, and that’s what I am going to undertake.

Stay tuned.

I may have already recounted the story of a presentation I was making at a regional woodworker’s club 25(?) years ago, and prior to my presentation there was a Show-N-Tell among the members, as there usually is for gatherings like this. Well, this particular episode was all about incredibly complex and even convoluted jigs enabling the members to not work wood but rather to machine wood with great precision. I recall rolling my eyes so hard it could probably be heard throughout the room. I mean, real woodworkers work wood by hand, not by machines or power tools and certainly not with jigs. Jigs! For cryin’ out loud. Were these guys even “real” woodworkers?

I have since become, to quote Lyndon Johnson, “Smarter today than I used to be.” Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

Roubo’s jig for gluing up coopered panels.

The second major barricade to fall in the bigotry against jigs was during the initial phases of the Roubo Project. Roubo was all about jigs, forms, and templates. In a world where the typical craftsman was only a few days ahead of malnutrition anything that helped get him from Point A to Finished and Paid For was a requisite component for working and getting fed, sheltered, and clothed.

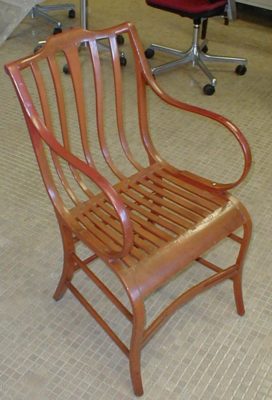

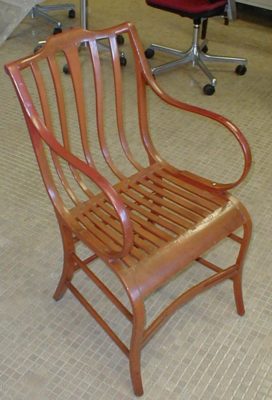

But the first hurdle for my obstinance was when I dove deep into the world of Samuel Gragg’s Elastic Chairs. There is simply no way to construct these without having a boat load of jigs for every step of the journey, from preparing the stock to steam-bending the parts to sculpting the seat rails and crest rail, through the ultimate assembly. I spent dozens of hours in that research trying many different schemes for the jigs involved.

When I started down the path of making a scaled-down version of the Gragg chair for L’il T I had hoped to have it done long ago, but then life interfered and I’ve just now returned to the shop after almost three months’ absence. I finally completed the inventory of jigs needed and will now turn my attention to prepping the hand-riven stock.

I’ve still got six weeks before his birthday…

Stay tuned.

Recently I’ve been developing some new bending forms and was steam bending some Gragg chair parts. Unfortunately(?) my steam bending set-up is on the fourth flour, an unheated space with great ventilation (read: wind blows through unimpeded). I remember filming some videos up there one winter and two kerosene heaters barely made a difference even though I was practically on top of them. I think in a couple of shots you could see my breath; not exactly the optimal conditions for working with hot hide glue.

Ditto steam bending thin parts, where in even the best of conditions I have a couple dozen seconds to get the parts bent around the forms and fixed in place until they cool and dehydrate into their set shape. The first recent session was on a cold, grey day and was miserable. I found that if I timed things just right, even on a cold day, if it was sunny and the air was still I could get the work done just fine. The reason was my 2500 s.f. of corrugated asphalt roofing overhead. Since the roof is completely uninsulated as the sun warms the roof it then radiates much of that heat downward into the attic space of the barn. My curiosity led me to point my laser thermometer at the roof at the peak of the solar gain — the underside of the sheathing was almost 100 degrees F! The result was a 20-25 degree gain in heat in the space.

I fully intend to exploit this in the furute with some fabricated passive solar units. Stay tuned.

2023 is shaping up as a pretty Graggtastic year in the shop. I am in the home stretch of the copious pinstriping for one chair to be delivered. A second client’s chair is fabricated but I have not yet begun the painting, and a third chair is about half built.

Then last week I was contacted by someone who has a Gragg chair with a broken arm, and based on the images they sent it just *might* be ONLY THE THIRD ORIGINAL, COMPLETE ELASTIC ARM CHAIR known to exist!

There is the completely overpainted chair at the SI that I kept in my conservation lab for almost two decades, trying unsuccessfully to persuade the curator to allow me to remove the overpaint.

Then there is the beauty at the Carnegie in Pittsburgh, and the heavily restored one in Baltimore. Unfortunately at the moment I cannot find my overall photos of the BMA chair but I have a large folder of detail shots. As I understand it the Baltimore chair was missing some elements that were newly fabricated and integrated to make a whole chair.

This newest chair has a tricky repair to be made to the arm, and the putative client inquired about me making a new chair to make a pair with the old one.

On top of all of this excitement there are several new Gragg-ish projects on the drawing board. Without revealing all the cards, consider that 1) we have a new grandson, and 2) the front porch of our Shangri-la cabin is rocking-chair-tastic.

Finally, I’m at long last seeing the light at the end of the tunnel for the “Build A Gragg Chair” video set. Whether that light is sunshine or an oncoming train I cannot yet be certain, but I remain hopeful. At the moment I am estimating the series to be more than a dozen half-hour-ish episodes, and Webmeister Tim and I are noodling the mechanism for the on-line offering. I’ve had one faithful donor sending me a small contribution every month (THANK YOU JimF!), but we need to come up with a system for processing the $1.99(?)/episode charge without viewers crawling up my back as the episodes are released. One approach I will almost certainly NOT take is a subscription model. I’ve spoken to some subscription-based content creators and they are unanimous in their regret. No matter how much content they create, their subscribers want more, and more often. I want no part of that.

Now the only thing left in the equation is the resolution to the question, “Why am I not as energetic and productive in my 68th year as I was in my 28th?”

‘Tis a mystery. Who knows, if I can solve that problem, I may even want to offer another Gragg chair workshop if there is interest.

I cannot deny that our spirits were vexed at the end of the second day when we had a nearly 100% failure rate bending the seat/back slats. We re-thought our process and examined the broken elements. It was then that I noticed ex poste all the failed bends were in kiln dried stock that I had planned for a different used and they accidentally went into the “bend” barrel. D’oh! We enacted a couple of minor ex ante revisions and combining these with the proper selection of wood we had perfect results and reveled in a couple days of almost 100-percent success (I think we had one failure and that might very well have been my impatience, bending the piece faster than it could stand).

I’ve had good and bad streaks of steam bending, but these were the most stark examples of the challenges inherent in taking wood to the brink of what it can be forced into doing. We rejoiced as the inventory of chair parts grew into that which was needed for next August.

For now the chair parts are just hanging off the beam, seasoning until used by the workshop students. I have some more Gragg projects of my own to work on so there will undoubtedly be more experience interacting with wood, steam, and forms.

During our recent days of work preparing for next August’s “Build A Gragg Chair” workshop my friend John and I prepped a lot of wood sticks, and bent them to the forms required to become Gragg chair parts.

We got the steam box set up, the forms set out, and set to work.

John hand planed dozens of chair pieces to get them ready for the thermodynamic adventure.

Once he had five or six pieces ready to go, he used the template board I created for this purpose and affixed the bending straps to all the pieces. When you have to execute two 90-degree bends only twelve inches apart in a dozen seconds, bending straps are pretty much mandated. We used flanged sheet metal screws and plumbing straps and attached them BEFORE they went into the steam box because the brief time to get the bending done after steaming does not allow for the straps to be put in place afterwards. And since the chairs get completely painted, any staining or screw holes can be dealt with.

I placed them into the already heating box and waited for them to reach maximum temperature, which in my set-up is about 200 degrees.

Using a state-of-the-art steam box seal we set the timer and waited the requisite time, 25 minutes for the arm and serpentine pieces, 45 minutes for the bent seat/backs.

On the first day we had good success especially with the thin pieces, only one failure out of eight or ten attempts, but on the second day we had a string of failures approaching 50% when bending the continuous seat/back slats.

At that moment we could discern no reason for the degree of failure We needed to re-think our process.

Recent Comments