Since one of the critical components for conserving The Lute Player was filling several cracks with pigmented wax for cosmetic purposes, I spent a fair bit of time with my favorite tool I have ever made. Made from a scrap of vintage ivory I bought from David Warther, this combination spatula and scraper was made just for working wax, and made just for fitting my hand.

I made the tips as curved, one wide (~1/4″) and one narrow (~1/8″), and roughly triangular in cross section. The flat surface, on the outside of the curve, provides excellent material manipulation and flattening. The edges work magnificently at trimming wax fills.

I shaped the blades with files and sandpaper, then polished them sharp with 600grit sandpaper wrapped around a 1″ dowel. For maintenance I do the same with even finer sandpaper.

When it comes to making wax fills in cracks, my favorite tool is this variable-heat stylus that is made to use in assembling wax models for lost-wax metal casting. While I do use it for that purpose, I find I use it more often for melting wax for linear fills.

Using this tool I flow in an excess of usually pigmented wax into the crack.

Then with my ivory tool I carefully scrape off the excess. The tool is so great that It rarely disturbs the material on either side of the fill.

Once the gross removal is complete I burnish the area with coarse weave linen to pick up any last little bit of the excess wax.

And with that the wax filling is complete and the surface is ready for inpainting and final toning.

With the legs ready for installation on/into the slab top, my next step was to get the underside of the bench reasonably flat. It did not need to be particularly smooth, and definitely did not need to be “finished” but it did need to be amenable to seating the legs into the mortises cleanly. Using a scrub plane and a #6 I got the underside ready to go.

With the slab top still upside-down but placed on lower stools, I simply put the leg tenons where they belonged and drove them into place. On one of the legs I was especially pleased that I had left the legs a little long so the results from the pounding with a sledge hammer could be excised. On two of the legs they went into place with just a bit of tapping with a wooden mallet, one took a bit more persuasion, and one was really tight. Often you do not know these things until it is too late to do anything about it except reach for a bigger hammer.

I am not particularly bullish on through-mortised stretchers for this type of bench, first because the bench does not need them for stability as the only real purpose for the stretchers is to hold a shelf underneath, and second it adds another element of unnecessary complexity to the project. In this prototype I cut some pieces of 4-inch wide 2x stock from the inventory, planed them lightly by hand, and affixed them to the legs with 3-inch deck screws for the short end stretchers and angled 4-inch deck screws for the longitudinal stretchers.

Laying over the bench on the low stools allowed me to hand plane the faces of the slab easily, and measure and saw off the legs to the length I wanted. I chose 36″ somewhat arbitrarily, we will try to fit each bench to their maker when we do this for real in July.

And with that, the bench was rotated another quarter-turn and sat upright on the floor. It does not budge a bit.

Next time I’ll finish up the core bench.

===========================================

If you are interested in joining me for a workbench building week at The Barn July 25-29, drop me a line.

Nowhere was Besarel’s virtuosity as a woodcarving sculptor more evident than in his rendering of the belt. This was all done with extreme delicacy as it was not only all short grain but also sculpted with a void from the torso in one six-inch stretch. It should be no surprise that the area had been broken numerous times, and when I encountered the sculpture the broken belt section was merely nailed to the torso and a small section of the loop was missing altogether.

To address this damage I embarked down a path that was entirely consistent with my conservatorial principles even though it might strike you as odd. I disassembled the damaged area and tacked the pieces back together with hot hide glue. This was entirely inadequate for the structural integrity of the object. Its only purpose was to provide fixed alignment for the elements.

To impart the necessary structural support I needed to augment the area, yet I did not want to “contaminate” it nor spend a lifetime executing something exotic. Instead I backed the damaged area with a material that was not only rheologically sympathetic but also even more stable longevity-wise than the wood — linen rag paper. I took a piece of 60-lb rag paper and cut it to the right size for the repair, then tinted it with gauche.

I slathered hot hide glue on the paper, slipped it behind the affected area, and slid some mylar and packed cotton wadding underneath that to provide complete contact with the verso of the damaged belt. (Yes I know it is a lousy picture, my camera was in the process of self-euthanization)

After the glue set over night I removed the wadding and the mylar barrier sheet, and stood back to assess the results. I was not displeased. It fits the furniture conservator’s “Six Foot, Six Inch Rule'” in that it is visually harmonious and not glaringly visible at standard viewing distance but readily apparent at close examination. Invisible repairs are rarely my goal, structural robustness and aggregate aesthetic integration are what I am shooting for.

Earlier this week I taught a three-day Traditional Finishing Workshop at The Barn, but since only one person signed up for it perhaps I should more properly call it a Traditional Finishing Private Tutorial. Whether he wanted it or not BruceK had me all to himself for the three days.

The syllabus for the tutorial was a very simple one, encapsulated in this graphic I devised seemingly a lifetime ago. We touched on each topic, sometimes repeatedly, and the days unfolded as a conversation with focused exercises to allow Bruce to leave with the the confidence and knowledge he needed to approach finishing fearlessly and skillfully. We were too busy working to take all the pictures necessary to fully represent the activities, but here are a few.

Since burnishing the wood with a polissoir has become integral to my own work in preparing the substrates for finishing, I introduced Bruce to the practice himself. Here he is tuning up his brand new polissoir with fine sandpaper to make sure the tip was a flawless but very slight crown. He made the other end flat, and used both ends extensively in the three days.

Here is his first try at it in combat, and he agreed the results were impressive.

We added four or five coats of 2 lb. lemon shellac to that burnished surface, let that dry until afternoon on the first day, then buffed it out with Liberon 0000 steel wool and Johnson’s Paste Wax. Bruce expressed that “this finish was exactly what I had envisioned” and thought that alone was worth the three days stuck with me in the hinterboonies.

We then dove into the techniques revolving around filling the grain with wax. Here he is finishing up the application of molten beeswax which will be scraped off leaving a filled surface ready either for buffing or shellacking.

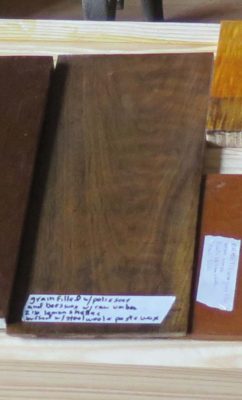

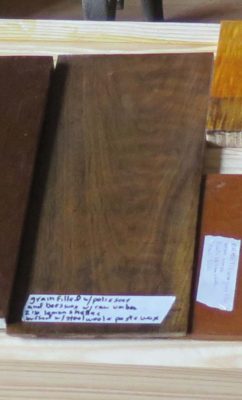

One of the variations on this theme was to fill the grain on this beautiful piece of walnut with solid beeswax scrubbed on the surface like rubbing it with a bar of soap, and sprinkled with some raw umber powdered pigments then all worked into the grain with a polissoir.

The excess wax was scraped off and the surface was shellacked a couple of times with terrific results.

We moved on to colorants, using this exuberant piece of curly maple as our palette. On one section we used asphaltum, probably the most widely brown-ish colorant in the days of old, on another we used high-tech organometallic dyes. I do not use chemical stains. Period. On the third section we just built up the lemon shellac.

On these two sample boards we applied asphaltum as a glaze over the initial coats of finish (rear) while on the other we used the asphaltum as a stain. I wanted Bruce to get a sense of how the same materials can perform differently (or not) depending on the situation.

I made sure to send him home with a lifetime supply of parging tar, which is what I use for asphaltum colorant.

Traditional finishing is a lot of burnishing and brushing, so there were a number of brushing exercises and a lot of discussion about good brushes to have in the tool kit. Certainly the most extreme exercise I like to employ is to use a giant piece of plywood as the foundation for building up a finish brushed on with a 1″ nylon-and-sable brush. The objective is to overcome the intimidation of working such a large surface with such a small brush, and to leave a finish that is flawless. This exercise is usually three “innings” of several coats of shellac. After the first inning dries it is sanded lightly with 320 silicone carbide paper, and after the second inning it is rubbed lightly with 0000 steel wool. After the third inning, which already looks pretty great, the surface is burnished vigorously (you cannot rub too hard or too long) with 0000 steel wool and paste wax. Spectacular, and all the more when you consider it is just a piece of cheap luan plywood from the lumber yard.

We also covered the brushes and brushing techniques needed for contoured and voluptuous surfaces such as carved moldings or Chippendale legs. Again, flawless results.

Of course we covered “French” polishing, beginning with the making of the pad itself with raw, combed and washed wool wrapped in a linen rag, and mixing up the spirit varnish for the pad polishing. I gave a short demo, yielding a glistening surface, then Bruce went at it. He was able to pick it up and with a little practice will have “the touch” cemented in his brain and hands.

We even got into making some custom paste waxes. In the first case Bruce mentioned that he’d finished a piece that seemed a bit too green/brown and wanted to add some red hints to the appearance. So, I made him lightly tinted batch of reddish paste wax.

Then we made a new batch of my Special #13 blend of paste wax. The picture is misleading as the wax is still molten, but it cools into a pale translucent mass ready to be put to work.

Just before Bruce departed I took a picture of the sample boards he had made. He left with an increased confidence and knowledge about finishing his projects, ready and eager for the next one.

I very much enjoy finishing and teaching about finishing, and expect to offer this workshop every summer at The Barn. Perhaps next year I can get twice as many students.

Once I finally had all the pieces accounted for in the line between the left elbow, the lute, and the right elbow I tried to reassemble them and wrap up the project.

Didn’t work.

Due to the wood shrinkage along that arc, which followed almost perfectly the tangential orientation of the wood, the region had suffered dozens of breaks and repairs, and was now at the point where the pieces simply did not make up the whole. Given that the lute body was pegged to the figure’s torso and that the arm was supposed to be in a fixed location, there was a space of approximately 1/8″ on the neck of the lute. That’s generally considered to be a problem when a construct with fixed ends does not meet in the middle.

My only real option was to disassemble completely all of the pieces in the region and augment them with a newly grafted spacer in the fingerboard. I began by gently torquing the left forearm which had been broken at some point in the past and reassembled (misaligned, alas) with a very large ~1/2″ pin and a gob of glue. Fortunately the repair had not held so I could get it apart with some gentle mechanical persuasion. I used DBE poultice (Safest Stripper) to remove the mass of PVA left behind, then trimmed the pin to allow for a correct alignment of the pieces back together.

With the pieces all apart I could get down to business. The first thing was to put the lute head back together. With a plexi caul on the fingerboard I used hot hide glue to tack the head to the neck at the proper angle. It was enough to hold things steady for back filling the sizable voids I described earlier.

Since the entire area of gluing surface was well-coated with hide glue I proceeded with making a fill of carvable epoxy that I mixed up myself as I described a couple of weeks ago. The fill material was mixed to be very stiff in working, almost like butter so there would be zero flow, but would be very light and carvable in situ. This worked exceedingly well as the fill was now approximately the stiffness and density of the wood and provided 100% adherence at the gluing margins. The surface of the fill was modeled with emery boards.

Th next step was to address the mess that was the lute neck. As I said it had been repaired multiple times in the past, none of those attempts particularly elegant. Again, DBE poultice did the trick in removing the fragments of the previous repairs and cleaning up the gluing surfaces. I “dry assembled” the entire composition at this point to see how much of a fill I needed to fabricate and insert into the void. This was not without its challenges as the area had been worked over so many time it left the pieces un-alignable to some degree.

Reassembly/gluing the neck together was a tightrope walking experience. There was no way to clamp anything together given the shape and delicacy of the pieces involved. Instead I placed the lute body in a vise with plenty of padding and oriented it so that the hand/neck/head mass would be perfectly balanced. Holding my breath I applied the hot hide glue, put the assembly together and aligned the pieces the best they would allow, and held it with both hands for two or three minutes until the glue began to gel. I left it overnight to dry.

The result was acceptable. I did have to trim a bit of original material on either side ex poste, which I am loathe to do, but it did allow for a strong reassembly.

The final hair raising step was to assemble the entire section together on to the torso. This was another instance where clamping was simply not possible. Very gently I placed all of the pieces together in the right orientation and alignment using ht hide glue. Since clamping was not possible the best I could do was hold everything in alignment with low-tack masking tape. Which is what I did.

The next morning it was together, soundly adhered and as stout as could be expected.

Perhaps nothing identifies the Roubo bench from all others like the beefy legs set into the double mortises, one dovetailed, through the slab top. For this prototype I simply chopped and ripped the 2×12 SYP stock to give me four legs of three lamina, 36-1/2″ long and 5-1/8 wide to give me a margin for trimming the length and planing the width.

To glue up these legs I used my favorite laminating clamping system, namely decking screws and washers. I’ve written about this before but forgot to take pictures this time, so I’m inserting a picture from a previous project where I used this method. I simply laid the middle lamina on the bench applied the glue, and placed the outer lamina offset along the length to slightly exceed the thickness of the top slab, and drove in 10 2-1/2″ decking screws with 3/16″ ID washers. (These washers left some substantial divots in the wood, so next time I will probably use fender washers instead). I flipped the assembly over and repeated the process with the opposite outer lamina, again off-set by the thickness of the slab, applied the glue, drove the crews and set it aside overnight. The next morning I removed and screws and washers and was ready to clean them up at the bench.

Fortunately my Emmert K1 was up the the task as always, as I planed the legs flat and true. Good wood, good tools, good time.

I wrapped up the leg prep with the single hand work step required for the project. since my goal was to make a prototype that could be replicated by the full range of woodworking aptitudes and experiences, yet come out the other end with a heritage quality bench, I was determined to keep the skilled hand-tool processes to a minimum. I think the number “1” meets that requirement. Using a rasp and a float to finish the fitting the legs were ready for insertion into the slab, which is what comes next.

===============================================

If you are interested in joining us for a week-long workshop to make your own heritage quality Nicholson-style or Roubo-style bench July 25-29, drop me a line.

With the core of the top glued up and scrubbed, I added the three lamina to each face with the openings cut out for the double tenoned leg ends. Since this was a down-and-dirty prototype I just used a chop saw to make the cuts of the 2x stock prior to assembling the bench top.

I marked out the mortises and just made each piece the correct legth for the opening, slathered on some yellow glue and clamped it up.

Mostly I needed a pile of clamps to hold it together and then some wet rags for the clean up.

As you can see my chop saw is barely carpenter grade. I think for the workshop we’ll use a cross-cut sled for the cutting the pieces on the table saw.

=========================================================

If you are interested in a week-long workshop for building your own heirloom quality Roubo or Nicholson style workbench July 25-29, drop me a line.

While conserving the wood sculpture “The Lute Player” I needed to carve some replacements for missing fingers on the sculpture. Have you ever tried to carved curled fingers in short grain softwood? Holding them little things is a pain. For a bit I contemplated making some non-wood replacements, such as making a wax maquette on the finger stub, taking a mold, then casting an epoxy replacement in place. In the end I concluded the the approach most beneficial for the long-term health of the object would be to simply carve some new fingers in similar wood. I chose some vintage Eastern White Pine with the exact grain orientation as the unidentified softwood of the original, and with approximately the same growth ring density.

To come to grips with the problem of carving short grain stubs I came up with a nice solution that undoubtedly a multitude of you have accomplished before. I glued some blocks onto the tips of a wood screw then excavated voids in the block faces that fit the fingers perfectly.

It made sculpting them a piece of cake. Most of the shaping was accomplished with a small Auriou Modeler’s Rasp or a beautiful Swiss file I believe is known as a barrette file I got from Slav the file pusher (just kidding Slav, it’s just that I have a weakness for elegant and exquisite files, and he is my supplier of NOS files).

Once the fingers were roughly correct I fitted their gluing surfaces to those on the finger stubs of the sculpture and glued them in place with 192 gram hot glue. Then I could make the surfaces of the new finger parts fit the adjacent surfaces and conform to the overall composition.

This was especially necessary for the index finger on the left hand; I simply could not figure out its exact proper position and shape until after I had glued the finger blank on the hand, then had the hand set in place on the sculpture. Once that was done the correct shape and attitude became readily apparent.

The final steps in this finishing process occurred only after all the reassembly was complete, but I wanted to present the process in toto, so do not be confused by the pictures as they seem out of sequence. Even the pinkie on the right hand, which I could ascertain the size and shape very closely as the digit above it was also detached, required some final shaping in situ. Since the piece was pretty small and mostly short-grained, I placed a felt pad and block underneath the fingertip, gently slid in a clothespin half to provide the exact amount of support, and finished it off.

At the recent Groopshop I was showing off the faux urushi hexagonal box I have been experimenting on, and the question of my polishing procedures came up. (I will be revisiting the issue of cissing epoxy very soon) So I thought I would go over it here. It is very similar to the procedures I use to polish tortoiseshell, about which I blogged last year I think.

For the most part I use a cut-up felt buffing wheel as my rubbing blocks that I charge with the abrasive polish. I probably bought this one on-line at Caswell or maybe even at a Woodcraft store but I honestly cannot remember precisely as it was many years ago. They do not really wear out, and I only discard them if they get contaminated.

As for the abrasive powders for final polishing I generally use three: 1.0 micron agglomerated microalumina, 0.05 micron agglomerated microalumina, and whiting. (At times I will use 4F pumice or rottenstone/tripoli to get the final stages, but then I switch to the metallography powders) The first two are ultra-fine abrasive polishes used for preparing laboratory samples for metallography or geological examination, the third powder is also used for mixing up gesso. The microalumina powders come from Buehler, and my favorite whiting for polishing is Gamblin brand I get from Dick Blick.

For the polishing slurry medium I use water, naphtha, or alcohol, depending on which is appropriate for the substrate being polished.

I make a point of cutting a polishing block for each grit, and usually for each material being polished. I mark them with permanent marker to help keep them straight. This pair of felt blocks are for use on transparent coatings, but I have a separate set for silver, copper alloys, tortoiseshell, and ivory.

For intricate surfaces I take a 1/4″ dowel and cut the end at a shallow angle, then epoxy a small chunk of felt to the end to use as my polishing surface so I can reach difficult or recessed locations.

I generally use Webril litho pads for cleanup of the dry abrasive powder afterwards. Alternately I might use hypo-allergenic cosmetics pads. Either way, I use them once and toss them into the trash.

Recent Comments