Here’s a sharpening tip I have used for the past several years.

In order to get the back-bevel secondary angle consistent and effortless, many folks use the “ruler method” and rest the back side of the blade on a metal ruler to get the back bevel/micro secondary bevel. Since some of my machinists’ rules have different thickness, in addition to the preference for not using an actual rule since they can move during the process, I pulled out a thin brass strip from my supply box and cut and bent it to fit the stone in question.

By overbending the tips a smidge the metal strip is basically spring-loaded into place, thus the micro-bevel jig stays put during the final few strokes of sharpening.

The brass strips are available at almost any hardware or hobby store, usually for a dollar or two. Obviously you could use any thin strip of sheet metal as well, flashing would work just fine.

There’s been a lot of “rearrangeritis-ing” going on in the barn as I try to organize and winnow the contents so that I can establish an honest-to-goodness estimate of the footprint I need to use, in great part to project into the distant future when we build our final, geezerized home some time in the 2030s.

Back in the day when I used to write a lot for PopWood one of my articles was about building and using something I called a Butterfly Sawhorse, that could be folded flat to hang on the wall or unfolded to operate as a very convenient work or holding station (I’ll post the article as soon as Webmeister Tim and I can figure out how to unlock the AWS archive where it is stored). In the maelstrom of rearangeritis I find myself using this tool almost every day.

One of the things I’ve always wondered about the Butterfly is, how much can it carry? To be technically dispositive about it I would load it up with weights until it collapsed, documenting the process exactly. But that does not strike me as particularly useful exercise is the results would be 1) a precise knowledge of the load bearing capacity of the Butterfly, and 2) a squashed flat Butterfly.

I did get a good sense of the Butterfly’s strength recently when I loaded it up with an estimated 700 pounds of really, really green walnut. It accomplished with task with nary a quiver.

Sometimes a willingness to venture “outside the box” yields great rewards. This is one of those times.

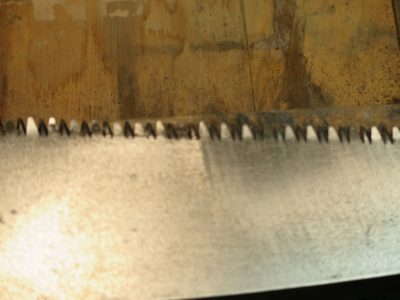

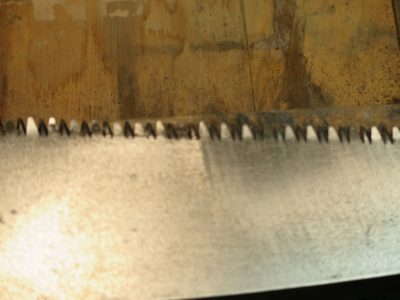

Like probably most of you I have a number of modern saws with impulse hardened tri-faceted teeth. The upside is that these teeth can be very long lasting. The downside is that they are brittle and prone to snap off whenever encountering an exceedingly hard material, such as a nail. I have several saw blades with a gap-toothed grin. Fortunately, the blades are almost always replaceable. Unfortunately, until recently, my experience had been that they were impossible to sharpen due to the impulse hardening that made the files skate off of them without affecting any improvement. I found this frustration to be true for any of the facet-tooth saws I have, whether actual Japanese saws or the Stanley western style saws that employ Japanese-style teeth.

While working at my daughter’s house a while ago with my old-ish Z-brand saw I hit a nail good and hard. Much to my surprise only one tooth snapped off, but a couple dozen were mushroomed (I’m not good enough with that camera to get a nice pic). I had never before seen this damage. Before, the teeth just snapped off.

I certainly had new replacement blades in the drawer, but since the teeth were intact (except for the one) I decided to bring it back to the barn and give it a try to sharpen them. Using abrasives, first sandpaper then one of my small whetstones, I flattened the back side of every damaged tooth. Since most of the saw’s use was for rough carpentry and yard work I went ahead and cleaned it up pretty well.

However, when it came to re-shaping the damaged facets even my diamond needle files mostly skated over the hardened tips. But there in my small container of whetstones for my carving tools was a diamond shaped aluminum oxide “India” stone. The cross section was exactly like that of the file normally used to sharpen Japanese-stye saw teeth. I also had a needle-taper stone of the same material. They both came in handy.

Setting up the sharpening station just like every other saw I’d sharpened in the past umpteen years, “filing” with the “India” whetstones worked like a charm.

In less than a half hour I had the task done. Prior to the sharpening the saw would still cut after a fashion, 51 strokes to get through a 2×4, but after the sharpening it made it though the same lumber in exactly 1/3 of the strokes, leaving a very nice kerf surface.

It is a good day when you can go to bed after learning something you did not know when you woke up that morning.

A couple months ago for my birthday Mrs. Barn gave me this remarkable tool to keep handy. I’ve had many headlamps over the years as my fading eyesight is always seeking more lumens, but this one is the first that I’ve tried that is actually comfortable, high performance, and long lasting. The combination of the LED illuminator plus the 2 AA batteries being located at the rear of the unit giving it a perfect balance, I can wear it all day long with comfort. I cannot tell the lifespan of the two ordinary batteries as I have not yet had them go dark after almost 60 hours of use.

She says she bought it at the local feed-and-seed coop, so I am guessing it may be available at Ace Hardware stores.

While working at the kids’ house I was relegated to a little spot in the unheated, concrete-floor garage. By the end of the first day my feet hurt all the way to my neck. No doubt about it, I am really spoiled by the floors in the barn. My shop there has wooden flooring over wooden joists, with 3/4″ rubber horse stall mats over them and I can stand there all day with no problem.

I was looking around for some mitigation to the floor situation and fortunately found two huge cardboard boxes, probably from new kitchen appliances. I spread them on the floor such that there were four layers of corrugated cardboard between my feet and the concrete and set about to working as normal. The difference/improvement was dramatic.

Though not quite as forgiving as my barn floor and not as durable either, this solution will definitely suffice for keeping me upright and out of pain for the duration. And if I wear out this new floor padding? No problem, there are more big boxes to use once these go into the trash.

Once my list of “Little projects” got whittled down I had some allow time and had fortunately grabbed a pile of stuff to sharpen, mostly damaged or never-used (by me) tools so I was standing up for long stretches working on my stones. The foot-comfort factor was high, thanks to nothing more sophisticated than sheets of cardboard underfoot.

Back by popular demand – sandblasting! I am delighted to profile my complete sandblasting system.

The starting point is my “nothing special” $75 Craiglist compressor in the basement of the barn, residing there because it is a diaphragm compressor head rather than a piston head and thus pretty noisy. The compressor unit is a 2 HP motor/head attached to a 10 gallon tank. The compressor is attached to the air-abrasive gun via a typical reguator/air hose system and quick-release pneumatic fittings. I generally operate my blasting gun at around 40 psi which gives me good control and adequate aggressiveness and is well within the capacity of the compressor.

The blasting gun attached to the hose is a siphon-feed unit, ancient (probably Craftsman) but indistinguishable from some thing you could buy tomorrow at Harbor Freight.

The system operates like this: The air running through the gun nozzle creates a partial vacuum in another feed-line fitting/tube which draws the abrasive medium through the siphon tube. In that effect it is identical to a paint spray gun, but instead of pulling up liquid paint and atomizing it through an atomizing nozzle it is sucking up the abrasive and focusing it through the gun output aperture. As a general practice I simply jam the end of the siphon tube into the bottom of the abrasive reservoir, almost always just a bag of the abrasive or a five gallon bucket if I am feeling fancy. I refill the bag/bucket with “overspray” abrasive gathered from the trash can. I’ve thought about getting a fixed metal “hopper” reservoir but the bag/bucket work just fine for me.

One final word: make sure to wear eye, hand, and face protection. Really. I generally use a face shield, light leather or rubber gloves, and a dust mask or respirator. You do not want to get even a smidge of this in your eyes or lungs.

===============================================

BTW I got my stitches out yesterday and much to the doc’s surprise I have had zero discomfort since Saturday, when I became pain free and cane free. As he commented, “This level of recovery is unusual for someone at your stage of life.” Apparently for geezoids like me the cartilage pain is compounded by an even more severe arthritis pain, which I do have some but not yet to the serious pain level. If arthritis is the foundational pain problem, repairing the cartilage will not diminish the pain to my current level of “0.” Still a little stiffness but that will disappear with motion and PT. I’ve been told to take it easy for a month, which I will probably sorta do. Off to mow the lawn.

The events of the past several months, including Mrs. Barn and me losing our remaining parents and my becoming closer to 70 than 60, are leading me on a path of deliberate winnowing of my shop and barn contents. Given that my sister is still going through my mom’s stuff — and she lived her last years in a one room “mother in law” apartment with my brother and sister-in-law — and the literal tons of belongings in my father-in-law’s four bedroom, two car garage house with a large back yard where he lived for 59 years, I am determined to reduce my material possession burden to my heirs as much as possible. Since my mom died at 103 I may have some time to get it all resolved, which is a good thing when there are 7,000 square feet and 70+ acres in the discussion.

Other contributors to this long-term process are the realizations that barn-based workshops will not have the prominence that I once thought would be true, and given my current set-up on the fourth floor I really do not need a second floor classroom outfitted with a perimeter of workbenches (I do however still use that space mostly for development of the ripple molding cutter). Also I recognize that at some point in time life in the mountains would just become too hard physically, and I would see the barn in my rearview mirror. Not any time soon, but it is inevitable in 10, or 15, or 20 years. One small step we are taking to delay that day as long as possible is to try to find someone who can execute most of the mowing and bush-hogging tasks around the homestead, but when you live in the least populous county east of the Mississippi River it can be a challenge to find someone to work for you.

One of my upcoming tasks will be winnowing the workbench inventory. Do I really need eight workbenches in my own workspace? Of course not. So, I will begin reducing that particular footprint almost immediately and there are definite “Workbench Wednesday” implications.

The first of these will be to replace my first workbench built for the space, the timber planing beam, with a low bench of the Jonathan Fischer/Roman/Estonian variety. Since completing my French Oak Roubo Project bench I have had no need for the planing beam so it will be resawn and joined to become the slab for that bench. It will occupy roughly the same space but serve a more immediate need as my knees and hips are becoming more troublesome and working while sitting is ever more congenial.

This change will also allow me to construct a standing tool chest to hold a copious inventory of hand tools, to be placed at the end of the low bench where my saw rack and metal hand planes hang on the wall. Since seeing Walter Wittmann’s cabinet a few years ago I have seen this as a solution to my tool storage problem and now is the time to act on it. The Japanese tool box will reside where Walter’s large lower drawers are located.

Of the plans for the workshop changes these are two of the three at the top of the list. The third is to restore my piano-maker’s workbench in order to make it a proper gift for my son-in-law, and move it out of my workspace. I m still cogitating on the ultimate home for the Studley-ish bench I built for the exhibit.

On top of everything else I have stock for at least another half dozen workbenches still unbuilt, but that may be moved on to other folks with the time, energy, and need that I do not have. Among these are the gigantic mahogany slab and vintage walnut 6×6 that would result in an eye-popping Roubo bench, a 14/4 curly maple slab already glued up, a stack of oak 10x15s, some 12-foot long 7×15 Douglas Fir timbers…

Stay tuned.

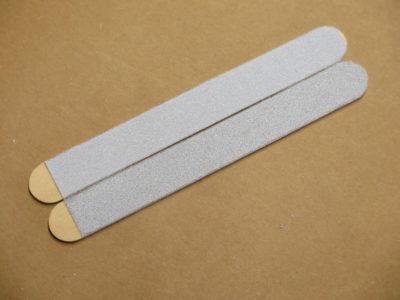

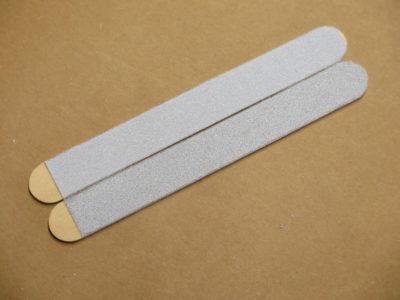

Decades ago I discovered the benefits of keeping a stash of emory boards at-hand in the shop. Bought at the local pharmacy I found these little tools to be a magnificent solution to any number ot abrading and shaping problems. Unfortunately, like a great many products over the years these have become too cheezy to really be the workhorses they used to be.

So, as I have posted previously, I make my own. One of my beginning-of-year habits is to make a new set of abrasive sticks, gluing sheets of sandpaper to tongue depressors with a spray adhesive and then cutting them apart into a pile of useful tools. (I really don’t need any posts about my New Year’s regimen of sharpening routine edge tools, do I?)

This year I did something a little different and expanded the variety of sticks. In addition to the typical pairing I’ve been using for a long time, a coarse side and a medium side of aluminum oxide abrasive, I added finer stearated silicon carbide papers into the mix. These options created their own issues, as I found the adhesion to be not as robust as with the AlOx paper. Using a small roller, made by and given to me many years ago by my pal MikeM, I found that pressing the edges worked well, plus I discovered the need to embed the sticks while the spray adhesive was still soaking wet.

I wound up making three different sets of abrasive sticks. The specs for each was detrmined by the abrasive sheets I had on the shelf.

The first set was pretty similar to ones I’ve made the past, this time with 60-grit and 100-grit sandpaper. I think that the 60-grit side will be less useful than I originally thought, but that could be because the product itself is pretty cheap and the abrasive particles spall off with first contact to the substrate. Next time I will aim for 80 and 120-grits.

Next up are the sticks using SiC papers, 150-grit and 220-grit papers. I’ve not made this combination before and think it will be a very satisfactory one.

Finally I went utra fine, with 400-grit and 600-grit together. We’ll see how useful these are in the coming days.

I’m now set up with this year’s inventory of abrasive sticks. Well, we’ll see if this lasts my usual full year since there are now so many different options.

Among my inventory of sharpening implements is an old 8000-grit ceramic water stone that I bought perhaps 35 years ago. I recently dropped it on a concrete floor with the resulting carnage you might have predicted — it snapped in two. Rather than toss it out I tried to salvage it and put it back to work.

Based on the character of ceramic sharpening stones, namely that by nature they are comparatively porous, the foundation existed for adhering the two pieces back together. In fact, since ceramic stones tend to be fairly soft and friable (fracturable) when adhering pieces of these ceramics together you have to pay attention to the adhesive-adherend margin, making sure that the density and hardness of the adhesive is congenial to the density of the adherend. While I cannot modify the character of the cured adhesive film, I can use other methods to modify its performance.

In this case I followed my longstanding practice of using dilute adhesive to size the gluing margin (the surface of the adherend), thus rendering something more hardened-sponge-like than a block of hard plastic in direct contact with the soft ceramic. The latter construct is much more likely to fail in somewhat short order as the harder, denser, and more cohesive adhesive breaks off some of the softer ceramic block, resulting in the failure. In this case I used an epoxy I had on hand.

I mixed the two parts thoroughly, then diluted it immediately with with acetone to yield a watery solution. This was applied directly to the broken stone surface, and soaked in to yield a fairly parched-looking surface. This results in an adhesive/adherent region perhaps ten or twenty of fifty times wider than that accomplished by full-strength epoxy alone. After a few minutes I added another application of the dilute epoxy, then set it aside until the epoxy was almost tack-free.

The it was ready for a bead of the full strength epoxy, which I applied to the lower half of the joint to make sure none of the full-strength epoxy would squeeze out the top glue line to excess.

Once the gluing surfaces were coated with the epoxy I placed the two halves together and applied very gentle clamping pressure, mostly to hold the two halves in correct alignment rather than drawing them together. Their fit was wonderfully tight from the git-go. There was a tiny bit of epoxy squeeze out on the top line, and I wiped that off immediately with a paper towel sodden with acetone.

I let the assembly sit until the epoxy was fully hardened, then re-trued the surface, first with a sheetrock screen and then with sandpaper over a flat surface. Since it is an ultra-fine polishing stone it does not need much water; to make sure the epoxy is not challenged I simply wet it on the surface instead of soaking the stone in the water bath.

In use there is a little click as the steel is passed over the fracture line, but the stone still works just fine.

A few days ago blog reader (and the Lou Gehrig of the woodworking blogosphere) RalphB asked about my use of the pumice block to smooth the surface of my parquetry Kindle case. The use of pumice blocks is well documented in historical accounts, although explicit or specific details are often missing.

I use a pumice block from the plumbing section of the hardware store (I order them by the case). Normally they are used for deep cleaning of porcelain and enameled fixtures to remove mineral deposits and stains. They work equally well for evening out irregular wood surfaces such as those found when assembling parquetry or marquetry from sawn veneers, where regardless of the care in the initial veneer sawing a fair bit of irregularity is manifest.

I generally use a pumice block as the step following the toothing plane/Shinto rasp, moving the block in a circular fashion on the substrate, yielding a fairly smooth and even surface about what you might expect with 60 or 80 grit sandpaper. Following the pumice block with a card scraper and polissoir, the result is quite pleasing.

Recent Comments