There is no doubt that perhaps the biggest player in the world of shellac literature is the consortium of interrelated Indo-British shellac institutions of which the London Shellac Research Bureau was prominent. B. S. Gidvani was the Director of the London Bureau when he compiled the volume Natural Resins as a treatise on the products from nature that functioned as raw materials for the emerging plastics industry. This book is especially valuable for seeing where chemical engineers saw shellac in the continuum of raw materials for manufacturing.

Here is the first half of Gidvani’s Natural Resins, with the second half coming in the next installment.

Enjoy!

I would not say that I have a vise, um, fetish. I will admit that I have long been fascinated with vises, and own what some folks – for example a bride of 32 years, just thinking hypothetically here — would think is an over-adequate inventory of them. The seeds of her view might have been planted when we were first married and students at the University of Delaware, and I learned about Carpenter Machinery in downtown Philly having a huge stock of Emmert vises salvaged from the recently-closed pattern shop of the Philadelphia Navy Yard foundry. We were poor as church mice, but for one of only two times while in college I took money out of savings and headed to Carpenter’s. I still remember the look on her face when I climbed into a four-foot-cube industrial storage cage and came out with two almost-100-lb chunks of iron to put into the car trunk.

They were complete Emmert K-1s. I built a bench around one, a bench I use daily ever since. The second one remains in the bullpen, awaiting its call to duty some time this coming winter.

In the years since I obtained and even built a number of vises, some based on specific project needs, some on testing out a “what if” idea, some simply whimsical. Machinist vises. Machinist vises with integral anvils. Twin screw face vises (on the back side of my Emmert-bearing workbench, and pretty much a standard feature on many of the workbenches I have built since).

Shop-built end vises (to be featured in a Popular Woodworking article next spring).

Rotating/tilting engraving tables/vises built with a duckpin bowling ball and two toilet flanges. Zyliss vises, of which I have four and find indispensable. Roubo leg vises. Saw sharpening vises.

The tale goes on.

Then three years ago, within days of each other, I had “in the flesh” introductions to both the H.O. Studley workbench with its nickel-plated piano-makers vises and the products of bench vise innovators Jameel and Father John Abraham. In the aftermath of those episodes what had been an abiding curiosity became something much more energized and focused.

Over the next year or so I will be combining the best features of all the piano-makers’ wheel-handle vises I have been able to examine thus far into a design and set of foundry patterns for making the ultimate vise of the form. Along the way I will let you peek over my shoulder as I travel down this path, hopefully one of fulfillment and not of merely enabling a compulsive addiction. In the end my goal is to have yet another new bench, this one an offspring from the splicng of toolism genes from Andre-Jacob Roubo and Henry O. Studley.

Now that will be something to see.

I hope there are no recessive gene issues…

With much anticipation I waited for the weekend in September 2009 when Rich came to install all the guts of the system and I could then connect the water line to it.

The only real requirement for the location of everything is that 1) the turbine had to be at the lowest practical spot on the property, and 2) the high powered (and expen$ive) electronics had to be protected from the weather. I decided to locate all of it alongside a garden shed next to the creek.

Rich came with his family and did his magic. Truth be told I did not have all of my prep work done but amazing things were accomplished that weekend.

First, Rich attached all the electronic gizmos to the side of the shed, building the complexity of components piece by piece. As he was doing that I was installing the housing on which the turbine would set.

Since the “shroud” was a five gallon bucket, all I really had to do was dig out a pocket for it to sit in and cut a hole for the water to escape and rejoin the creek. (This procedure of extracting water from a creek on your property and returning it unchanged to the creek while still on your property is known as “non-consumptive use” and is, I believe, unregulated in all states. Check with your local officials to confirm this.)

Once Rich was done with the installation of the electronic hardware, including hooking up the turbine, the giant battery bank and connecting the 6/3 cable running up to the barn I built the cover for it, simply hanging a closet on the side of the shed. That structure still houses the electronics to this day.

I got done with the fussy plumbing fittings at the bottom and hooked up the water line to the turbine.

The water flow was very low, which is normal for the end of summer here, but still it was producing 4 amps at 48 volts, for just under 200 watts continuous, or about 4 to 5 kilowatt-hours per 24 hours. Not gobs of power, but you would be surprised what could be done with that much electricity.

I could hardly sleep that night. Several times in the night I went outside to sit on the front porch and simply listen to the soft whine of the turbine.

Within the fortnight following, the service box in the barn was installed and the wiring began. In those evenings i would saunter out onto the front porch, just to watch the lights in the barn gleaming in the night. Over the years the wiring network has expanded to the point where it now encompasses all four floors of the barn, and runs pretty much whatever I want to run. I cannot use unlimited electricity around the clock in perpetuity, but if you came to spend time with me working in the shop and did not know we were off-grid, you would not notice anything unusual.

Up next – The First Major System Upgrade in 2011

During my recent foray into Georgia for the French Oak Roubo Project I carried a special gift for Jameel Abraham. In great part due to his work with making ouds, a Middle Eastern stringed instrument vaguely like a lute, he has developed a passion for intricate tiny mosaic patterns. In the 19th century a similar art form know as sadeli grew in eastern Asia Minor and in the Anglo-Indian territories of the raj.

I have several pieces of sadeli, including an amazing lap desk of mosaic parquetry-and-ivory applied to a base of yellow sandalwood. I also had a beautiful little calling-card box of sadeli and ivory (the size appropriate for holding business cards), which I thought should convey to him for inspiration in his work. Not that he needs any; Jameel is perhaps the most inspired and inspiring artist I know.

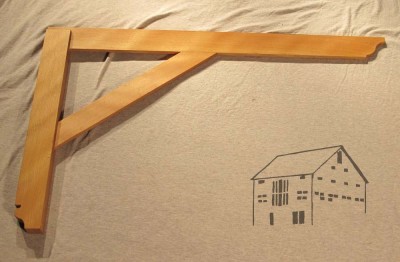

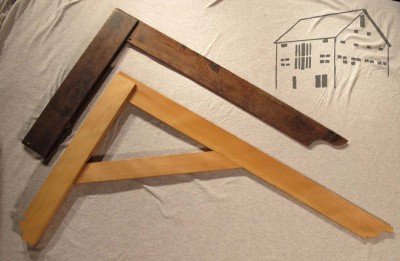

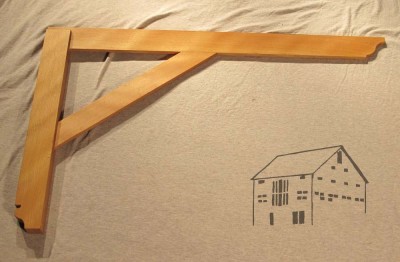

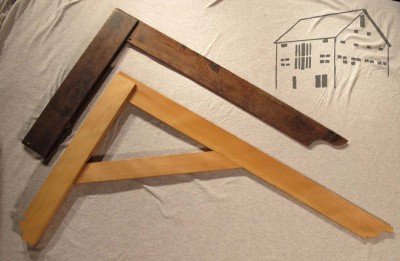

Anyhow, Jameel being Jameel, he was constitutionally unable to accept a gift without giving one in return, and this is what he bestowed on me – a hand made 24” Roubo styled square. It is an extraordinary addition to my tool kit, one that has already been effortlessly integrated in to my work. It is also a terrific companion to a simpler Cuban mahogany square I bought for next to nothing many years ago simply because it had a broken blade. You can still see the remnant of the damage of the blade just before it enters the beam. Fortunately the pieces fit together perfectly and I was able to reclaim it from the burn pile with almost no effort or time.

Both squares have magnificent, understated detailing, and are treasures in my tool set.

In 2006 I contacted Rich Buttner of Nooutage.com in Richmond to help me with the electrical engineering, which he did with experience, knowledge, skill, attentiveness, and excellent customer service. A retired power plant engineer who launched a business in the back-up energy world, Rich was excited about contributing to his first complete hydroelectric home-based system. I have been so pleased with Rich’s contribution that he remains my “go to” guy whenever I need advice or hardware about further improvements to my concept.

As he was spec-ing out the project and assembling the hardware, I went to work.

In late 2006 I got my hands dirty for the first time. I had already located the highest elevation on our property where the stream could be harnessed. About 100 feet from where the creek crossed the property line there was a narrowing to about 6-feet that was perfect for a small dam to serve as a capturing basin for the system.

Using sandbags filled with dry concrete I built a double coffer dam about 2 feet high and ten feet wide, about two feet thick. It did not have to be big, it just had to steer the water into the penstock (the pipe that carries the water down hill). I accomplished this task by embedding a 10” culvert into the dam, which in turn channeled the water into a capture basin, which itself was connected to the water line.

Somewhere around this time I ruptured a disc hauling piles of 16’ 1×12 siding up a ladder and nailing while I hooked a leg around the ladder, so I wound up delaying everything by almost two years for rest and physical therapy (with a healthy dose of “Don’t do that again!” scolding). Eventually I was back to full strength and ready to proceed with making a capturing/diversion basin and laying the pipeline.

Since I was still working a the Smithsonian at the time, for a capturing basin I used a museum-quality plastic tub underneath the outflow of the culvert pipe, which I fitted with a museum quality shower drain, which I then attached to a 2” PVC fitting. I topped it off with a home-made Coanda screen filter on the top to keep the debris out of the tub but allow for full capture of the water.

It was then that my friend DickP enhanced his account in the Bank of Don by coming up for the weekend and helping me haul, arrange, fit and connect over a quarter-mile of 2” Schedule 40 PVC pipe. Seriously, I am in his debt more than I can fully articulate. At the end of the weekend we had a continuous line of 2’ PVC from the dam to the powerhouse where the turbine was going at the bottom. I opened the valve at the top and water flowed out the bottom. That was a joyous day!

At this point I will comment on the shortcomings of the workshop I first attended. They really gave short shrift to the construction and more importantly the “lay” of the penstock. Over the years I have been helped by friends and siblings to modify, disassemble and reassemble, and reroute the penstock four times to get it right. Perhaps I am simply stupid, certainly I am stubborn, but more understandng before beginning this stage would have saved me a boatload of trouble. Finally this past spring my friend TomS and I got it right, and I do not foresee any changes at this point other than repairs from falling trees or rolling boulders during a flood or some such.

Up next – Hooking It All Up

I recently returned from almost a week getting the barn and the cabin ready for winter habitations, inasmuch as this will be the first winter in which we actually habitate them.

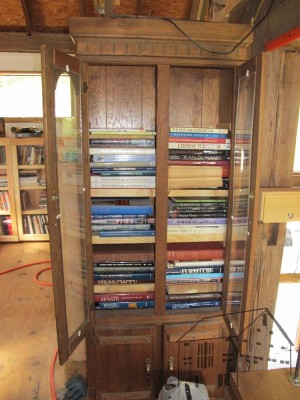

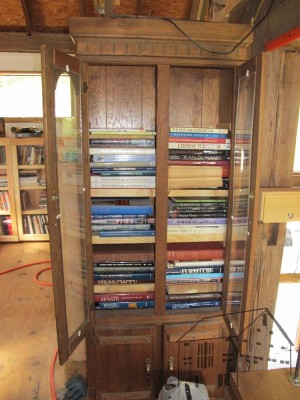

One of the big tasks was to make progress in the library, completing more of the uber-low-tech bookcases to house the thousands of books that need to reside there, along with re-purposing other cabinets like this one used for oversized books.

My activities took me through my studio frequently, and I could not help but notice the gaping void in the middle of the space. I created that void for something special, which has not come to full fruition yet.

But, my day is coming.

PS Here is the latest picture of the library. The big honking slab of working table in the middle of the floor is actually a 30” x 2” x 16-foot piece of eastern white pine that is probably 150 years old. When I get the time I will make a trestle refectory table out of it for visitors to use for reading, writing, or dining. Since the books will all be behind glazing, eating there is okay.

I am not especially proud of condition of the basement (first floor) of The Barn. Perhaps I am unique, but over the seven years of construction on the project has led to a state of near total entropy in the lowest space. At first it became a repository for a lot of building supplies because it was convenient. Then it became the holding bay for all those scraps that “might be needed real soon,” finally it just sat there, full of construction detritus preventing the space from being better used simply because cleaning it out just never percolated to the top of the priority list.

Once we decided some months ago to permanently relocate to the Fortress of Solitude in the mountains, I knew I needed to address the state of chaos reigning in the basement, if for no other reason than I needed to install a more potent heating system than a single kerosene heater for my workshop space. Fortunately my pal Tony had acquired for me a superb used cast iron and ceramic wood stove, but I did not want to put it in my shop, I wanted to put it under my shop. Hence the need to clean out the basement underneath so there would be space for the stove to sit and gently radiate the heat up into the work space.

With Tony’s assistance I arranged to hire two sturdy lads, Chris and Jamie, for a day to get the basement cleaned out and ready for further configuration. What I had been delaying for several years, they accomplished in five hours! The basement was emptied of all the debris, and the good stuff was hauled down the hill and stacked neatly in the lower log barn.

Here are the two great discoveries I made (well, maybe three.) One, there was a great pile of what could best be described a waste wood. To deal with this we had a vigorous burn pile roaring through the day and the following day, with still a pile more to go. Since this was mostly coniferous wood it was inappropriate for burning in the wood stove for heat this winter. Second, there actually was a whole lot of useful material still in the piles, just needing sorting and stacking, to be processed further. All that material I needed to finish the battens on the siding of the barn is now stacked neatly , awaiting my attack with a circular saw and a fence. Also, I found some really spectacular materials underneath the piles of debris!

Since the barn is now configured differently than it was originally, there are several large timbers now available for some other purposes. Most notable among them are several full dimensioned 6x6s from select grade southern yellow pine. They are so dense it is almost like picking up a slab of concrete. These will almost certainly become part of a workbench at some point in the future. Combined with other stacks of SYP and white oak timbers I had already stacked in the lower barn I am pretty well set. Until the next pile becomes available…

The real treasure at the bottom of the pile was a vintage hand-worked southern yellow pine 13-foot 8×10. I had been wanting a new, longer planing beam and I think I have found my material for that. The beam was so huge that Chris and Jamie were unable to lift it from its perch on pallets. That will require a bigger crew than just the three of us. But it certainly was like a surprise gift under the Christmas tree.

Of course the most important thing to learn (again) that eager, younger, stronger backs are a bargain for us almost-60-ers.

When I returned back home from the microhydro-electric workshop at SEI I had a fairly clear idea about the logistical and technical requirements for my system. There were several integrated elements.

1. A body of running water. Check. While the flow was variable, the creek on our property had never gone dry in recent memory, so I figured all was well. The hydrology is so unusual around here with all the porous limestone and aquifers you can hardly throw a rock without hitting some kind of running water. This county has between 400-600 creeks, some of which are seasonal.

2. A way to get that water contained and downhill. As a practical matter this meant using a PVC pipeline to capture all the water I could as high as possible to exploit the inherent energy contained in running water. Given our hydrology and topography I figured I could get somewhere between 30-50 gallons per minute from an elevation about 100’ higher than the power plant.

3. A mechanical device at the bottom of the pipe to generate power from the force of the water jet coming out of the pipe. The evident answer based on the technical literature was a “Pelton wheel” turbine, which is basically a tiny(!) Ferris wheel which is turned by the water jet. The whole “machine” fits on top of a 5-gallon bucket! My turbine is 4” in diameter and the 48-volt heavy-duty truck alternator attached to it can produce more than a kilowatt of power if the water flow is enough. Mostly I get somewhere between 200-500 watts continuous output.

4. A method to store the power being created by the turbine. Giant truck batteries were the answer to the problem. I started out with four big deep-cycle batteries, the kind used for diesel truck engines.

5. A sophisticated system of electronic devices to control the electrical output from the turbine, to feed it into the batteries and dump the excess when they got full.

6. A high-power inverter system to transform the DC current from the turbine, and then feed the power to wherever I wanted it to go. The tail end of this system was standard wiring throughout The Barn. The “business end” was a matched pair of 48v input-to-110v output inverters in parallel, so I could have 220v in The Barn if I need it. In between was a 330’line of 6/3 cable fed through a shielded flex conduit.

At this point let me invoke the Schwarz Disclaimer — all of the products I cite in this series of articles are devices which I paid for in full, and get no benefit or consideration from their manufacturers nor distributors.

Up next — Building the System

In my opening entry to this blog I promised to present accounts of things other than historic woodworking or artifact preservation, with the emphasis on our evolving homesteading lifestyle. This is the first of those posts, as it begins a periodic recounting of the independent electric system we use for The Barn, and eventually for the cabin as well.

Being “off grid” is fundamental to the identity for The Barn on White Run. In part a lifestyle/political statement (I am fine with power companies but do not trust their political masters as far as I could throw a piano — virtually every gripe I have with public utilities stems from the regulatory bureaucracies governing them), in part a technological challenge (What? Just plug it into the wall? There has got to be a more complicated way to do this!), and part utilitarian practicality (out in the hinterboonies the power is interrupted a lot), the ability to work independently of the increasingly fragile power grid is a balm to the psyche. That has been especially true during periods of extended power outage, for example during the 2012 derecho storm when the power was out for more than a week. I continued work in the barn as though nothing had happened.

I am about to embark on several upgrades to my power system over the coming weeks and months, but I thought I would give you a glimpse of where I have been so you can better appreciate where I am trying to go.

Building the barn was accomplished with only a generator and power tools. My little Coleman with a Subaru Robin engine is apparently indestructible. After more than 1500 hours it still starts on the first pull and runs until I turn it off. (I could usually get about five or six hours per gallon of gas) A lot of time the generator was simply charging the 18v battery packs for the power tools, so rather than wasting an 8hp motor for that I got a teeny 1000 watt unit similar to this, that often gets about eight or ten hours per gallon of 2-cyle fuel.

I could have remained “generator only” for an indeterminate time, but making the barn fully wired required a more robust system.

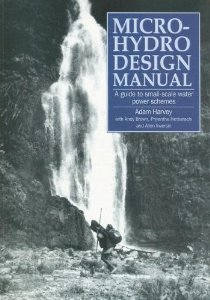

Almost eight years ago I began to design our current system, its subsequent installation being the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. When originally searching for property in the late 90s, independent energy production potential was prominent on the “Wish List” menu. In the climes of the rural Alleghenies this meant hydroelectric power.

After we bought our place the wheels began to spin in hyper speed.

First, me being me, I read everything and bought every pertinent book I could find on the subject of micro-hydroelectric power. You want literature on producing your own power at home? Look on my shelf. It’s probably there.

Second, I searched far and wide for a practical workshop on microhydroelectric technology. Eventually I flew out to Colorado to attend a micro-hydropower workshop at the Solar Energy International. The course had a definite “Che was here” feel to it as most of the students appeared to be self-indulgent professional sandalista misfits pretending to follow their revolutionary catechism, while two or three of us were interested in actually building residential power systems rather than overthrowing political kleptocracies in the third world. The course was good as far as it went, but the holes in the content were large and did not become apparent to me until I built my own system.

Up next – the elements of my initial independent electrical system

Reposted from the Lost Art Press website

================================================

The standard edition of “To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry” is now available for pre-publication ordering. If you order before Oct. 10, 2013, when the book ships, you will receive free domestic shipping.

The standard edition of “To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry” is now available for pre-publication ordering. If you order before Oct. 10, 2013, when the book ships, you will receive free domestic shipping.

The book is $43 and is available in our store here.

We had announced earlier that the book would be $40, but because of some last-minute changes to the printing specifications, we had to raise the price to $43. Apologies.

About the Book

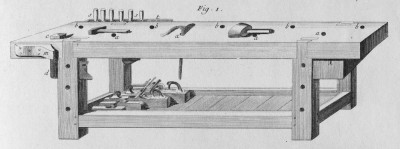

“To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry” is the first English-language translation of the most important woodworking book of the 18th century.

A team of translators, writers, woodworkers, editors and artists worked more than six years to bring this first volume of A.-J. Roubo’s work to an English audience. (Future volumes of Roubo’s other works on woodworking are forthcoming.)

While the title of this work implies that it is about marquetry alone, that is not the case. “To Make as Perfectly as Possible” covers a wide range of topics of interest to woodworkers who are interested in hand-tool woodworking or history.

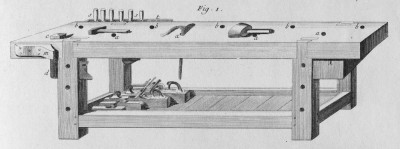

In addition to veneer and marquetry, this volume contains sections on grinding, sharpening, staining, finishing, wood selection, a German workbench, clock-case construction, engraving and casting brasses.

But most of all, “To Make as Perfectly as Possible” provides a window into the woodworking world of the 18th century, a world that is both strangely familiar and foreign.

Roubo laments the decline of the craft in the 18th century. He decries the secrecy many masters employed to protect craft knowledge. He bemoans the cheapening of both goods and the taste of customers.

And he speaks to the reader as a woodworker who is talking to a fellow woodworker. Unlike many chroniclers of his time, Roubo was a journeyman joiner (later a master) who interviewed his fellow tradesmen to produce this stunning work. He engraved many of the plates himself. And he produced this work after many years of study.

The Lost Art Press edition of “To Make as Perfectly as Possible” is printed to high standards rarely seen in the market today. Printed and bound in the United States, the 264-page book is printed on acid-free #60-pound paper in black and white. The pages are Smythe sewn so the book will be durable. And the cover is made from heavy 120-point boards covered in cotton cloth. The book is 8-1/2” x 12”.

In addition to the translated text, essays on the text from author Donald C. Williams and all of the beautiful plates, “To Make as Perfectly as Possible” includes an introduction by W. Patrick Edwards of the American School of French Marquetry, an appendix on the life of Roubo and a complete index.

The book’s table of contents is below and here. You also can download a sample section of the book here on sawing veneer with this link: Roubo sample pages.

“To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry” is available direct from Lost Art Press and from our select retailers.

To Make as Perfectly as Possible

The Different Woods Appropriate for Cabinetry

Section I.

Description of the Woods of the Indies, and Their Qualities, Relative to Cabinetmaking

Alphabetic Table of the Foreign Woods

Why Not Dalbergisterie?

Descriptions of French Wood Appropriate for Cabinetry

Colors in general, and the Woods from the Indies and from France with Regards to their different colors and their nuances

The different Compositions of Dyes appropriate for dyeing Woods, and how to use them

Section II.

On the sawing of Wood appropriate for Cabinetmaking

On Sawing Veneer

Description of Cabinetmakers’ Tools

Section III.

The Frames [Cases] appropriate to receive Veneerwork, and how to prepare them and construct them

Of Simple Parquetry, or the Composing of it in General

The Parqueteur’s Tool Kit

Section I.

The diverse sorts of Compositions in general: some detail and the Arrangement of wood veneer

Various sorts of Compositions, straight as well as circular

Make Banding With Roubo’s Template Blocks

The manner of cutting and adjusting the pieces so they are straight, and the proper Tools

Cutting and Assembling Cubic Hexagons

The manner of cutting curved pieces, and the tools that are appropriate

The 18th-century Shoulder Knife

Section II.

The manner of gluing and veneering Marquetry

Why Does Hammer Veneering Work? And How Can it be Made Better? 117

Section III.

The way to finish Veneer Work, and some different types of polish

Finishing Marquetry

Ornate Cabinetry, Called Mosaic Or Painted Wood, An Overview

Section I.

Elementary principles of Perspective, which knowledge is absolutely necessary for Cabinetmakers

Section II.

On the manner of cutting out, shading and inlaying Ornaments of wood

The way to engrave and finish wooden Ornaments

Section III.

How to represent Flowers, Fruits, Pastures and Figures in wood

Floral Marquetry

On the Third Type of (Veneered) Cabinetry in General

Section I.

Description of the different materials that one uses in the construction of the third type of veneered Cabinetry

On the Nature of Tortoiseshell

Mastic and ‘Mastic’

Section II.

Works for which one uses the third type of Cabinetmaking

Section III.

How to work the different materials that are used in the construction of Marquetry, like Shell, Ivory, Horn, etc.

Section IV.

The manner of constructing Inlay and finishing it

I. General Idea of the different types of Mosaic

Metal Casting

II. Ornaments in Bronze in general

III. The way to solder the Metals which one uses for different works of Cabinetry

IV. Description and practice of a Varnish appropriate to varnish and gild copper and other metals

Conclusion to the Art of Woodworking

Appendix: André-Jacob Roubo

Index

— Christopher Schwarz

Recent Comments