In preparing and packing the truck load of material traveling with me for the upcoming HO Studley exhibit, I was once again struck by the similarities and idiosyncrasies of the eight piano makers vices that will be on display there. What prompted my devolution into this indulgence of my vise vice was the adjacent proximity of Dan’s vise and Tim’s vise sitting on a wooden slab.

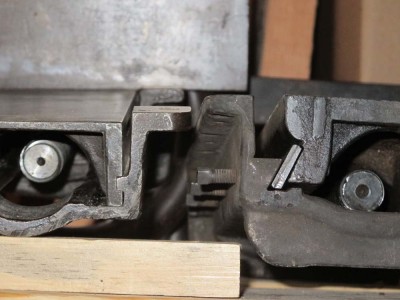

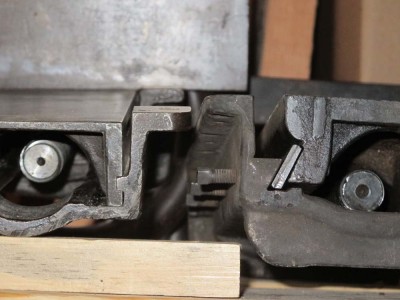

At first glance you might be forgiven for thinking these were two identical units, notwithstanding the dimensional differences. When they are turned over you begin to see some differences, but they still look like they are from the same lineage.

If you work up the strength to turn them around to look at more of the business end (Tim’s vise is about 60 pounds, Dan’s is almost 90), it is clearly apparent that there are some profound differences in the morphology of the frame-and-platen configurations.

On Tim’s vise, the ways are square-bottom channels with matching shapes on the platen. There is no adjusting these. Studley’s vises are of this configuration.

Dan’s ways are considerably different, again while providing the same tool functionality. In his case the ways are machined dovetails with on spaced to allow for the insertion of a pressure bar, which through the adjustment of square head gib screws determine the “tightness” of the unit.

And when you toss Mike’s vise into the mix, head scratching is the result, as the movable carriage is outside the frame that is fixed to the underside of the workbench. Where did that design come from?

Only one of the multitude of mysteries about these magnificent tools. I look forward to showing them to you at the end of next week.

Integral to the in-production book Virtuoso and the upcoming exhibit on the same topic, I am striving to make it more than just a tool peepshow. You are gonna learn something even if you do not want to!

Part of that learning experience will be the exposure to the remarkable Studley workbench and vises (above), including a display of similar contemporaneous vises that have been loaned for the exhibit.

To carry the weight of these six vises (somewhere in the neighborhood of 500 pounds) I built a fairly faithful replica workbench top, sitting on a base made for the exhibit but which will be swapped out for a cabinet base at some point.

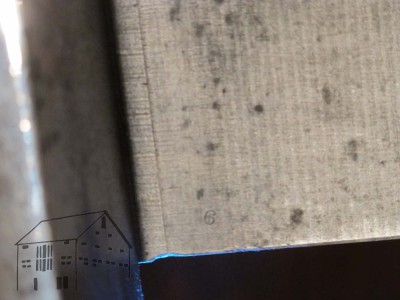

About the only semi-tricky part of the bench build was dropping the end vise dog slot with my 3-1/2 hp plunge router, the only power tool that makes me nervous.

With multiple measurements and confirmations, I cut the channel from above and below, and the vise and its dog yoke dropped into place cleanly.

Now I can put the router beast away until I need it again in several more years.

To increase the didactic function I left the front edge of the replica bench unfinished so you can see the core construction. As soon as the unit is back home the already-constructed front edge will be installed. Another thing to occur after the exhibit will be to dispense with the glossy finish applied for the display (four coats of Tru-Oil, then buffed) through the vigorous use of a toothing plane to leave the surface I prefer.

I don’t have any pictures of the finished bench with all the vises on it. I mounted them when it was upside down, but could not budge it to flip it right side up until I had removed all the vises. So, you will just have to wait on that visual for the exhibit itself.

The replica workbench top continues apace. I got the top smooth enough (more about that in a day or two) to seal it with my preferred benchtop finish of 1/2 tung oil with 1/2 mineral spirits, and about 2% japan drier.

I like this finish as it soaks into the wood deeply and provides a nice robust seal to the wood.

For the exhibit the top will be pretty smooth, but once it gets back home I will achieve my preferred top surface by cross-hatching it with a toothing plane, a technique I learned from my long-time friend and colleague, and Roubo project collaborator, Philippe Lafargue. But for now it is nice and smooth.

I fabricated the exhibit base for the top from three 1/2″ Baltic birch plywood boxes, fitted them to fastening battens, and temporarily assembled it in order to layout all six of the vises going on it for the exhibit.

One of the beauties of this exhibit is that it may be the only time in their lives that patrons to a museum-quality exhibit will get the chance to touch and manipulate historic artifacts, namely the six vintage vises hanging from the new bench top.

===================================

If you would like to experience the bench top in person, and oh by the way see the entire Studley Collection, there are still tickets available here.

It was more than a week into Spring, and being this Spring the sun rose to reveal an inch of icy snow coating everything the morning we were to visit the incomparable Conner Prairie historic complex, one of the nation’s premier enterprises of historic reenacting and interpretation. Once the slop was scraped from my truck we were on our way; one advantage was that the bitter cold kept the crowd small and we had the place nearly to ourselves.

One of the highlights was the timber frame barn in the Conner homestead. The main cross-beam is a gargantuan oak timber more than 12” x 24” x 40 feet long (the historic carpenters there figure the tree trunk was more than eight feet in girth) and the longitudinal mid-rafter beam was an 8×8 perhaps 70 feet long.

I especially enjoyed our time in the carpenter’s shop, where my wife and I were the only visitors. This allowed for a lengthy conversation with the proprietor about tools, wood, and their lathe. He showed it to me and allowed me a turn.

It is a magnificent shop-built machine with a 300-pound flywheel that can get away from you fast! Since I am a head taller than “Mr. McLure” it was very awkward for me, but I could see one of these fitting into the fabric of The Barn.

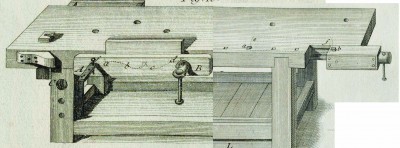

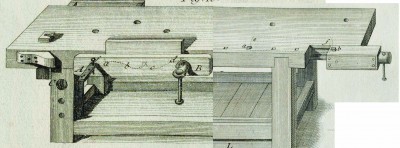

In the center of the one end was the impressive work bench, which had been built in the shop in years past. A copy of no specific documented model, it is instead a combination from a historically accurate vocabulary.

It seems to be about two parts Roubo with one part of Moxon and a dash of Nicholson. The six-inch-square oak legs are capped by a four-inch slab top, and the fixed deadman is stout as well. There is no real woodworker in America who would not be delighted to have this beast in their workspace. I know I would.

If you are going near the Indianapolis area, take a peek.

Last week I finished the photography for my next article in Popular Woodworking, about “The Butterfly” an innovative sawhorse-type accessory I invented for the workshop or even around the house. I think it will be in the June issue, but don’t hold me to that.

Thus far I have worked with Glen Huey at PW, but he is moving (organizationally) over to American Woodworker. I will miss working with Glen, but the way I look at it his arrival over at AW simply provides me another outlet for woodworking verbiage. I’ve already started pitching article ideas to him, including one about the Ultimate Portable Workbench I invented, and would like to build another one for the article. We’ll see if he bites on it. If not I will chronicle it here.

Since returning from my last trip to WIA and the Studley photoshoot I have been spending a lot of time this week completing the photography for an upcoming Popular Woodworking article , in the February issue I think. The article describes my design and construction for the bolt-to-the-front-of-the-bench wheel-handle tail vise I added to my workbench, with enough information so that you can make your own for whatever needs you might have. If you have a table saw and drill press and can order materials on-line, it is a piece of cake.

I needed to make this vise because my existing workbench for the past 30 years could not accommodate a Benchcrafted vise, and I wrote the article because I am surely not the only person who’s bench has the same or similar limiting characteristics.

I’ll be bringing it to next Saturday’s SAPFM Virginia Chapter meeting in Winchester VA for the show-and-tell session before main speaker George Walker‘s presentation.

The crew at PopWood are all woodworkers and a real pleasure to work with. If you have any ideas for an article, just drop a line to Megan, Glen (with whom I am working on this one), Bob, or Chuck. They genuinely enjoy helping you make the idea into an article. Really, let them know

Stay tuned.

My pal MikeM is fond of saying that the whole point of enduring our adult jobs is to get to the point where we are free and able to engage in interesting projects with great people in fun places. Such is the case with VIRTUOSO, my in-process book about the tool cabinet and work bench of Henry O. Studley.

Collaborating with photographer Narayan Nayar and editor/publisher Chris Schwarz is an ongoing delight. The project patron and owner of the Studley ensemble is a man of astonishing accomplishments and insights whose company I relish. Our work setting within his menagerie is about the most wonderful work environment I have ever experienced as an aesthete and artifactualist. This definietly fits the description of what MikeM describes as the point of work.

Immediately after wrapping up WIA in Cincinnati we loaded up the car and headed to North Tulsapolis, Montaska for my fifth visit to the collection for our final scheduled session of photography. What made this trip extra special was that on this time we would be joined by vise maven Jameel Abraham to provide me another set of expert and experienced eyes in my final examination of the vises on Studley’s bench before I ramp up weaving all the research into a compelling book.

As is usually the case, Jameel’s reaction to the ensemble was stasis. He stared for several minutes before I cajoled him into the work at hand.

Like me and all who have witnessed this before him, Jameel was much impressed by a face vise that opened 16″ with zero wiggle. I mean zero.

The information in just this image is worth many thousand words of description.

Finally, after some pathetic nagging from me, he opened his copy of the Deluxe Edition. His silent smile was gratifying.

Yup, interesting projects, great people, fun places.

I would not say that I have a vise, um, fetish. I will admit that I have long been fascinated with vises, and own what some folks – for example a bride of 32 years, just thinking hypothetically here — would think is an over-adequate inventory of them. The seeds of her view might have been planted when we were first married and students at the University of Delaware, and I learned about Carpenter Machinery in downtown Philly having a huge stock of Emmert vises salvaged from the recently-closed pattern shop of the Philadelphia Navy Yard foundry. We were poor as church mice, but for one of only two times while in college I took money out of savings and headed to Carpenter’s. I still remember the look on her face when I climbed into a four-foot-cube industrial storage cage and came out with two almost-100-lb chunks of iron to put into the car trunk.

They were complete Emmert K-1s. I built a bench around one, a bench I use daily ever since. The second one remains in the bullpen, awaiting its call to duty some time this coming winter.

In the years since I obtained and even built a number of vises, some based on specific project needs, some on testing out a “what if” idea, some simply whimsical. Machinist vises. Machinist vises with integral anvils. Twin screw face vises (on the back side of my Emmert-bearing workbench, and pretty much a standard feature on many of the workbenches I have built since).

Shop-built end vises (to be featured in a Popular Woodworking article next spring).

Rotating/tilting engraving tables/vises built with a duckpin bowling ball and two toilet flanges. Zyliss vises, of which I have four and find indispensable. Roubo leg vises. Saw sharpening vises.

The tale goes on.

Then three years ago, within days of each other, I had “in the flesh” introductions to both the H.O. Studley workbench with its nickel-plated piano-makers vises and the products of bench vise innovators Jameel and Father John Abraham. In the aftermath of those episodes what had been an abiding curiosity became something much more energized and focused.

Over the next year or so I will be combining the best features of all the piano-makers’ wheel-handle vises I have been able to examine thus far into a design and set of foundry patterns for making the ultimate vise of the form. Along the way I will let you peek over my shoulder as I travel down this path, hopefully one of fulfillment and not of merely enabling a compulsive addiction. In the end my goal is to have yet another new bench, this one an offspring from the splicng of toolism genes from Andre-Jacob Roubo and Henry O. Studley.

Now that will be something to see.

I hope there are no recessive gene issues…

Chris Schwarz just posted my newest contribution to the Lost Art Press Blog. You can see it here. My ongoing exploration of these vises and my efforts to replicate them will mostly occur ay my blog, so stay tuned.

Recent Comments