Whenever I am working on a project and encounter an impasse I do not stop working, I simply work on something else for a time until I can get back in the groove for the original undertaking. Such has been the case with A Period Finisher’s Manual, which has turned out to be much more of a grind than I was expecting. Even when taking a break from APFM and blogging I do not necessarily stop writing, I simply write about something else. Recently that “something” has been some fiction projects, one being some dalliances into Christological fiction regarding Joshua bar Joseph the young craftsman, and another being a panoramic thriller in which the Paris of Roubo’s time is a prime setting. In researching that topic I began reading David Garrioch’s The Making of Revolutionary Paris. Though not especially pertinent (yet) to my story line I found this passage compelling. In it, Garrioch is describing the city’s odors that blind beggars used for navigational aids.

They cannot see and do not heed the summer sun shining on the tall whitewashed houses that makes the eastbound coachmen squint under their broad-brimmed hats. Nor do they see the flowers in pots on upper-story window ledges, the washing hanging on long rods projecting from the upper windows, or the colors of the cloth displayed for sale outside the innumerable drapers’ shops in the rue de St-Honore. But they are sensitive, more than other city dwellers, to the fragrances of apples and pears of many varieties (many that the twentieth century does not know) , of apricots and peaches in season: to the reek of freshwater fish that has been too long out of the water; to the odor of different cheeses — Brie and fresh or dried goat cheese. The street sellers display these and other produce on tables wherever there is space to set up a portable stall. For the blind the smells are signposts, markers not only of the seasons but also of the urban landscape. They recognize the pervasive sweetness of cherries on the summer air or the garden smell of fresh cabbages in winter, marking the stall of the woman who sells fruits or vegetables at the gateway of the Feuillants monastery in the rue de St-Honore near the Place Vendome. The aroma of roasting meat from a rotisseur in a familiar street, the smell of stale beer at the door of a tavern, the sudden stench of urine at the entrance of certain narrow alleyways; these are the landmarks by which the sightless navigate.

In the early eighteenth century there was no escape anywhere in Paris from the pungency of horse droppings or the foulness of canine or human excrement. Like human body odor, it was ever-present but normally unremarked. Some quarters, though, were distinguished by other, more particular smells. The central market — les Halles — was unmistakable, with its olfactory cocktails of fruit, vegetables, grain, cheese, and bread. “It is common knowledge,” wrote an eighteenth century critic, that “the whole quarter of the Halles is inconvenienced by the fetid odor of the herb market and the fish market: add to that the excrement, and the steaming sweat of an infinite number of bests of burden.” Even when the market was over the odors lingered. The stink of fish bathed the arc of streets from the rue de la Cossonnerie to the rue de Montorgueil and St-Eustache. To the south, rotting herbs and vegetables polluted rue de la Langerie, th rue St-Honore, the rue aux Fers. Worse exhalations rose from the neighboring Cimetiere des Innocents, from the huge pits where only a sprinkling of lime covered a top layer of bodies already beginning to decompose. In the summer only the hardiest inhabitants overlooking the cemetery dared open their windows.

Other neighborhoods had different smells to contend with. Around the river end of the rue St-Denis were streets here the passers-by were overwhelmed by the smell or drying blood: “it cakes under your feet, and your shoes are red.” The beasts once killed, the tallow-melting houses near the slaughterhouses produced even fouler and more pervasive odor. Through the archway under the Grand Chatelet prison and along the quais of the city center the air was heavy (especially in the summer) from the effluent of the great sewers that oozed into the Seine between the Pont Notre-Dame and the Pont-au-Change. Even in the otherwise pleasant gardens of the Tuileries, a witness tells us, “the terraces .. become unapproachable because of the stink that came from them … . All the city’s defecators lined up beneath the yew hedge and relieved themselves.”

Ahh, Paris, the city of romance.

Recently while working to impose order to the library of the Barn I came across a pile of articles needing scanning and formatting for posting to the web. “Tortoiseshell and Imitation Tortoiseshell” was my contribution to a 2002 conference that required travel to Amsterdam for the presentation itself, in complete disregard to one of my personal mottoes, “If I ain’t at home, I’m in the wrong place.”

The scanned article is now in the “Conservation” section of the Writings section of the web site. There are two versions, one about 4.5 megs and another about 1.5 megs. I’m still working through the idiosyncrasies of my scanner and compewder, figuring out what settings work best. If I can get this better I will upload that version later.

Recently I have been spending some time trying to impose order and completion to the Barn library, which might be a fancy way of saying I have been throwing away boxes full of paperwork from my career at the Smithsonian. My departure was six years ago, and at this point I am pretty certain I no longer need any organizational files from that era. As a result I have about a dozen cubic feet of fire-starting material.

An unexpected(?) result of all this commotion has been that I’ve (re)discovered a number of things I have written over the years. Not Schwarzian by any measure, but a fair pile nonetheless. Articles in magazines, chapters of books, handouts for presentations, and monographs for newsletters, etc. While the Writings page of donsbarn.com already has a goodly number of these missives, there are even more that have not arrived there yet. So I have set up my ancient laptop and scanner to capture these electronically and make them ready to post both on the blog and in the “Writings” section.

I should have the first one ready to go in a couple days, and hope to post a new one each week.

Oh, and I am working on readying some more material for the Shellac Archive as well. I still have a full “banker’s box” of material to scan. All tolled I have about 8,000 pages of shellac stuff.

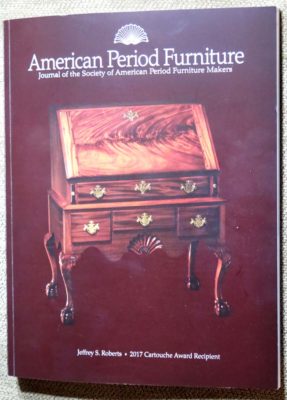

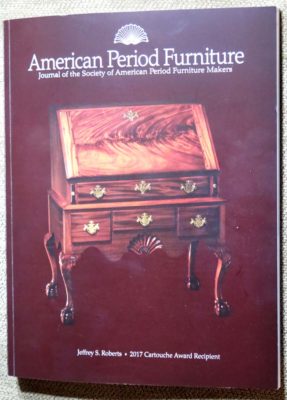

I rarely post about something that is current, but I found a package on the front porch when I came down for lunch yesterday. Inside was the new issue of American Period Furniture, the annual journal of the Society of American Period Furniture Makers. I have been a member of SAPFM for many years, and served a couple terms on the Society’s governing body.

Last year I was invited to be the banquet speaker for the annual Working Wood in the 18th Century conference at Colonial Williamsburg. Since the SAPFM always holds their annual business meeting and banquet at this conference there were plenty of members in the audience that evening.

They must have liked the banquet talk because I was immediately asked to turn it into an article for APF. I did, and it arrived this week. I forget whether this was my third or fourth APF article.

I will be blogging about each the 10 exercises in the talk and article at greater length in the near future.

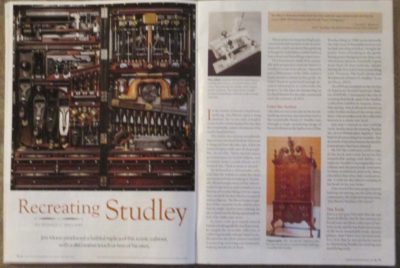

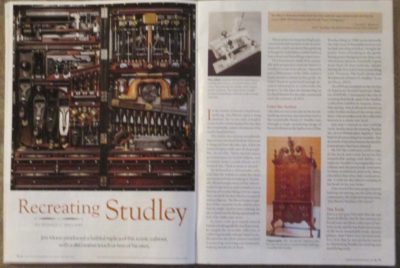

About eighteen months ago I contracted with Popular Woodworking magazine to write a pile of articles, and the final one of that batch was featured on the cover of the current issue.

This article was the feature on Jim Moon’s recreation of the HO Studley tool cabinet and workbench, which was indeed masterful.

The image of that new treasure has been popping up in disparate places. It deserves the widest possible dissemination.

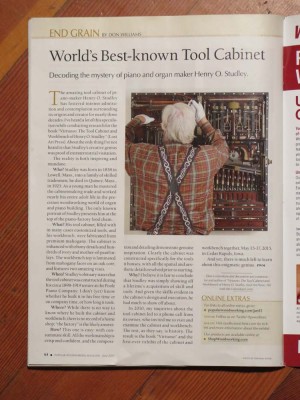

I’ve been a reader of Popular Woodworking for several years, and in recent times have enjoyed a very congenial working relationship with them. I just got the latest PW Issue 218, which is a terrific and not just because I have two things in it. There are several great articles including the cover project and a long insert.

The magazine features my article on decorative wire inlay (bisected by the aforementioned insert) and the End Grain column about the Studley Tool Cabinet that ran on the Popular Woodworking web site a few days ago.

Mrs. Barn glanced through the issue and said, “Very nice article. (I think she was talking about the Studley piece — DCW) But when are you going to start making furniture for me?”

Ouch. I guess I know what I’m doing after the Studley exhibit.

Yes, I am “all Studley exhibit, all the time” for the next month, but that tedium (?) was punctuated by a banner week at the Post Office box.

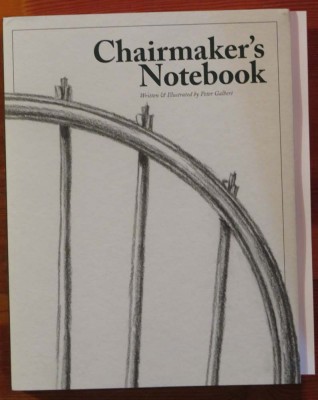

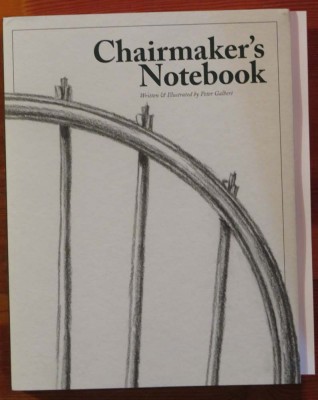

First came the brilliant Chairmaker’s Notebook from Peter Galbert. It arrived just in time for one of my periodic days at the ophthalmologist’s office (the periodicity depends on which of my eye diseases is acting up, and how severely) during which I had time to read a good part of it carefully and browse all of it to the end. The book is only partly about making Windsor chairs. In truth it is really about the way to think about, and the way to do almost anything of real consequence.

I am not a Windsor chairmaker and unlikely to become one other than as an amusement, my chairmaking runs from Point A, Gragg chairs, to Point A’, making slightly different Gragg chairs. Still, Peter’s eloquence and deep understanding, and the exasperatingly skillful manner of conveying them, made me smack my forehead repeatedly with the silent exclamation,”But of course!” while simultaneously silently muttering, “Man, I wish I had written this.”

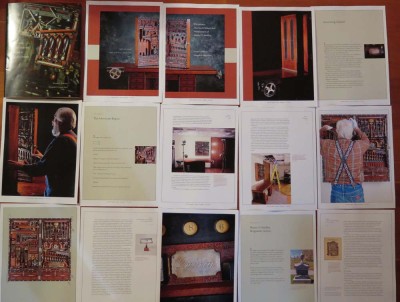

I also received the printer’s proofs from Virtuoso, and to tell you the truth, the combination of the sumptuous imagery contained therein combined with the realization that almost five years of work are nearing the end made a sizable lump in my throat. It has been a project of passions — sometimes love, sometimes hate — as are most such undertakings, but it it noteworthy to celebrate its conclusion.

Finally, my good friend of three decades Dr. Walter Williams just send me a signed copy of his latest book. A collection of scores of columns, it will make for enticing bite sized bits of common sense wisdom.

All in all, a good week at the post office.

Several months ago I received an invitation from a South Florida custom millwork and fabrication shop to speak at a luncheon banquet celebrating their 25th anniversary. At first I was ambivalent about the invitation as I didn’t know the folks, but Mrs. Barn was very enthusiastic about the prospect of a trip to the warm sunny climes at the tail end of a brutal winter in the mountains. As my correspondence continued with my host and the themes emerged for the presentation, I too warmed to the idea. By the time we plowed through the snow on our way out of town I was really looking forward to it.

The audience was designers, architects, and contractors, and I did my best to turn them into historic finishing enthusiasts. As I told them at the beginning, “My task is to show you a door, and open it just a little bit so you can see inside there’s a party going on. And the name of the place behind the door? The Finishing Room!” They were very receptive.

In the weeks leading up to the event I made dozens of sample boards so that every table had a complete set to fondle and admire as I talked about them.

In coming posts I will walk you through the samples I made.

It was great fun and reminded me how much I love woodfinishing, and the delight I will take over the next three or four years while crafting my gigantic Historic Finisher’s Handbook.

Thanks AWC and Catie Q for the invitation, you guys were great hosts and I hope to see you again! (and Mrs. Barn loved basking in the warmth and sunshine). I think late winter trips to Florida may become part of the routine.

For much of the past month I have been working on a set of sample boards for an upcoming address to a luncheon banquet of folks involved in mostly architectural interior finishes. It reminded me once again how much I love finish work, and caused me to ruminate on undertaking my long-desired magnum opus. I’m now committed in my heart to finally put pen to paper and create that mammoth manuscript I’ve been mulling for a long time, beginning next autumn, extending perhaps into the following two years. It will be part finishing room bench manual, part materials science treatise, part historical review, part aesthetics, and a large part recipe book.

The sample board set included things like glazed panels, limed panels, burnished shellac/wax, shellac pad polishing (aka “french polishing” even though the French probably call it “English polishing”), waxed French polishing, raw polissoired surfaces, fumed oak, japanning foundation, and finally a piece of true “bog oak” salvaged from a dismantled antique dam.

Now all I have to do is my part in getting Virtuoso: The Tool Cabinet and Workbench of Henry O. Studley 100% done (I’m going today to get the page proofs printed in color to finish my review), Roubo on Furniture Making revised and into the Lost Art Press production pipeline, and the Studley tool cabinet exhibit done.

There was a beautiful sunny vista of the mountains outside my shop window late this afternoon, just after I finished taking the photographs for the PopWood article on wire inlay. The article was a lot of fun to write, for a technique I have been toying with for some time, with ever widening applications. I think it is in the upcoming April or May issue, so check it out when it arrives on the shelves.

Recent Comments