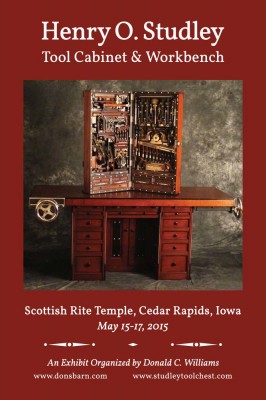

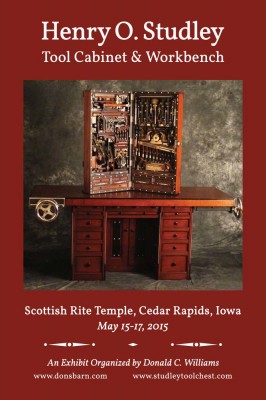

Recently I ran into someone who expressed dismay that the upcoming exhibit Henry O.Studley Tool Cabinet and Workbench was sold out.

“Where did you get that idea?” I asked.

“I tried going in to buy mine on the second day they were available and had no luck, so I figured it was sold out.” Convinced of the unavailability he had never returned to see the status of the exhibit or its web site.

I reassured him that this was an artifact of the total meltdown of the web site in the first hour of tickets going on sale several months ago. If he returns to the site, all is well and functional.

It occurred to me that others might be thinking the same thing, hence this post to remind everyone.

The truth is there are still plenty of tickets available, and you can order them now. I do not have the spreadsheet in front of me right now, but I am pretty sure there are still time slots that could accommodate a woodworker’s guild or any other groups who wanted to purchase tickets and make it a shared experience.

Spread the word.

If you have any questions, drop me a line at the contact page of this site. And make sure to check out the goings-on for Handworks, occurring at the same time and only twenty minutes away.

Our final day for the recent Boullework marquetry workshop included wrapping up our sawing,

assembling the finished patterns,

and gluing them down to supports.

For small compositions I am a big believer in using bricks as free-floating dead weights to hold them steady while the glue sets. I think these will be used as project starters in the future.

The students also had time to examine their tordonshell they made on the first day, which had air dried until the end of the second day and then spent the final night and day in the dessication chamber. Thus they had their own pieces to take with them, along with the leftovers from the pieces I’d made for the workshop. They’ve got plenty of tordonshell to experiment with several new projects.

I also allowed them to practice with two important tools. First, the chevalet,

and second, the Knew Concepts precision saw (full disclosure — I often collaborate with Knew to give my two cents about developing new tools and uses for those tools).

A grand time was had by all, and I enjoyed it immensely. I look forward to the next time I teach this workshop.

I unpacked the new silicone rubber mold and wooden pattern for the new beeswax mold, then tried it out with some molten beeswax I had previously processed. Success!, and I am pleased with the outcome.

Production has now begun. Thus far I have orders for about 300 1/4-pound blocks. I should be caught up with these orders in less than a month.

If you would like any of this hand processed beeswax, drop me a line at the Contact portal of this site. The slightly-more-than-a quarter-pound block is $10 plus shipping. This is the beeswax I use myself when doing Roubo-style finishing, and demonstrate using it in the new video Creating Historic Furniture Finishes that PopWood released a little while ago.

Once the Studley book manuscript is submitted in about a month I will turn my attentions to many new projects, including the creation of new finishing products including pigmented waxes and “Mel’s Wax,” the revolutionary high-performance furniture care product invented in my lab at the Smithsonian.

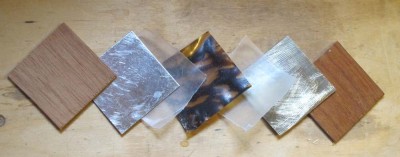

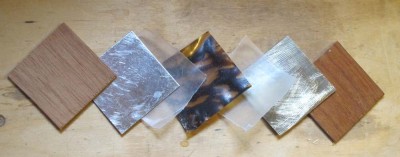

We hit the ground running at about 9 this morning with the review of Boulle-work, and then assembled packets for the first sawing exercise, whose only real function was to get newcomers comfortable with the tool and technique of sawing at this scale. Boullework is essentially a fret-sawing technique, and I started everyone off with a copy of their initial to saw in three parts; copper, pewter, and tordonshell.

The first step was to cut all the pieces in the packet the same size,

then score one face of the metal pieces to serve as a cleaner gluing surface. This meant that all the work was being done in a mirrored pattern to the final workpiece.

We assembled the packets with 1/8″ plywood as the bottom face, followed by the copper layer, followed by a piece of waxed paper (as a sawing lubricant), then the piece of tordonshell followed by another piece of waxed paper, then the pewter layer and finally another 1/8″ plywood face.

Veneer tape wrapped around the corners held the packet together, and the pattern was glued to the face of the plywood with stick glue.

Everyone used the same type of saw, a traditional German jeweler’s saw, fitted with 6/0 blades.

Getting the teeth in the right orientation was a challenge, given the near-microscopic size of them. I prefer these tiny blades as they allow for more detailed cutting, and leave such a tiny kerf.

A hole drilled with an eggbeater drill gave entre’ for the blade to be inserted through the packet,

and sawing could begin.

The scale of the sawing is tiny, and so is the saw dust.

The results of this introductory exercise was gratifying.

We then made some tordonshell, with everyone getting their hand in the process.

The second, larger packet was assembled, and the sawing began on the more complex pattern.

Here is how far we got today. More tomorrow.

Recent Comments