One guy, two workbenches, in three days.

Note: Obviously these are not perfectly literal days, as my time was scattered among many competing needs during this period; other work around the homestead, getting ready for gardening season, other projects in the studio. In reality this took small pieces of seven days, but I’d estimate that if I was doing nothing else it would take me three short days of work to accomplish.

On the second day I undertook the gluing up of the bench top slabs and legs, such that each slab was half of the final bench top so that I could feed these through the power planer prior to gluing the two half-slabs together.

The only notable aspect of this process was my “clamping” mechanism, the theory of which took me back to the pattern shop lo those many decades ago.

But let’s start with the glue and the spreading thereof. My jug o’ PVA had been laying on it’s side, unmoved, since the workbench build last summer. The combination of time, lack of motion, and its residence at the far end (and hence colder) of the studio transformed it into a sickly yellow pudding. I got some out of the jug and examined it, assuring myself the change was purely physical and not chemical. The oligomers were not fusing into polymers so the almost-gallon of glue was salvageable.

I cut open the jug and plopped the contents into a wide-mouth PET jar and turned loose my hand drill holding the paint stirrer on it after adding a smidge of water. Soon enough the stiff pudding turned into a sludge consistency which was good enough for my needs at the moment.

Harkening back to one of my favorite past times of watching youtube videos of Japanese craftsmen I decided to try their method of using a spatula for glue application rather than our more typical brush or roller. I did not want to spend any time making a special, probably disposable, spatula for this endeavor so I looked around to see what I could find to suit the bill. Sure enough, the near-perfect tool was sitting right there on the shelf along with its siblings. A package of very nice carpentry shims was just the trick.

The tip was tapered and thin, making it flexible and well-suited for applying the glue, breaking up any remaining globs during the spread-out. This spatula came in handy in another couple of minutes as well during the “removing excess glue” portion of the operation.

I glued up the first iteration of the assembly with clamps. I discovered immediately that this approach, while manageable with two pair of hands, is unwieldy and aggravating with only one pair of hands. Since I generally view complex gluing as an operation whereby going slow is the best way to go fast, I broke it down into component sub-operations amenable to my being only one person most of the time. Occasionally I am more than one person, but that is primarily for conversational purposes late in the day after working alone for several hours on mundane tasks. Even then this circumstance does not provide any additional help to the tasks before me.

In the pattern shop almost everything we fabricated was “un-clampable.” Our two go-to methods were rub joints followed by a lengthy time of leaving the workpiece alone, and gluing-and-nailing, followed the next day by the removal of the nails with a nail puller. Here I employed a variation of that theme.

Instead of glue-and-nails I used glue-and-decking-screws with fender washers to maximize the clamping power of the screws and keep the screw heads from burying into the wood. With 4″ screws I could assemble four laminae at once — screwing from both sides — which suited me just fine. I did that four times as they were the inner core for the four half-slabs. I used a C-clamp for aligning the edges of the laminae.

Once each screw-up was completed I removed the glue squeeze out, again using the shim/spatula to scrape it off. I found that I could then reclaim about 3/4 of the excess glue, making the wipe-up easy and fast.

While those four assemblies were set aside I moved on to the outer three laminae for each half-slab, the mortise joinery for the double-tenoned legs yet to come. I layed out the locations and spacing of the mortises, then cut the adjacent pieces to fit. I screwed these in place one piece at a time, working my way through the four half-slab assemblies in turn. By the time I got done and moved back to the first one for the next layer, the previous screw/clamping had set enough that I cold proceed.

I let them sit overnight for the next steps.

Thus something that could have been a hurried nuisance became a much more controlled and congenial success.

I am clearly not the sharpest knife in the drawer, as a belated lesson today confirmed. I have long used the table saw to make bigger pieces of brass and aluminum into smaller pieces for specific projects.

I needed to make some small square pieces of brass from the bar stock inventory I keep on hand. In years past, and I mean many years, I would shroud myself in all kinds of protective gear from the waist up to diminish the discomfort of being blasted with tiny needle-like chips of metal being hurled my way at high speed. Heavy apron, work jacket, leather gloves, full face mask, the whole works.

Suddenly in a flash of inspiration I arrived at the same point probably all of you discovered eons ago.

How about sawing the brass using a completely different set-up, with a sacrificial scrap on top of the work piece, and the saw blade teeth raised enough to cut the brass on the table but not so much as to cut through the waste scrap?

I gave it a try. Perfect. No shrapnel. Zero.

That sound you heard around 4 o’clock was me smacking my forehead and berating myself in most graphic terms for being so obtuse all these years.

Of course part of the blame was y’all’s since none of you told me this before.

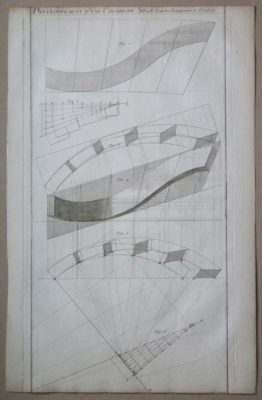

Print 239, “Development of the Curves of Seat (Back) Twisted and Flared” is one of those bittersweet, paradoxical entities in my inventory of original First Edition L’art du Menuisier prints I will have for sale at Handworks. On one hand it is a magnificent composition worthy of Edward Tufte, whose book on visual presentation of information sits well-used on my shelf. Roubo crammed so much information on the page it is almost mind boggling. It is in my mind nearly the equal of Minard’s famed print demonstrating Napolean’s March of 1812.

Typically Roubo would create a plate such that it left a margin of an inch or so all around the page. Not so with Plate 239; he composed it all the way to the very edge of the page, making it utterly unique among the book’s illustrations.

Which brings me to an economist’s best friend, “the other hand.” This idiosyncratic feature was lost on the barbarian who defaced the original First Edition from which my inventory derives. The knuckledragger chopped a quarter inch off the top and bottom, alas rendering it a badly defaced artwork, although none of the visual presentation in the field is compromised. That which remains is in excellent condition, but the key phrase is “that which remains.” It is probably un-Christian of me to want to dig him up so I could whack him with the shovel. May he rest in peace (and the entire artifact world said, “Amen. At least he cannot damage any more.”)

The mutilation Print 239 suffered forces me to make it the lowest price of any Roubo print I will be offering. Had that not occurred, it would have been among the highest priced.

This print was drawn and engraved by Roubo. But our unknown malefactor chopped that information off the bottom of the page.

$75

Now that the last extended hard freezes are over for this winter past, we may still get a number of frosts, I decided to get the hydropower system up and running. I walked the water line the other day all the way to the top, and am delighted to report that for the first winter since installing the system eight(!) years ago I had zero freeze damage to the line. The amount had been diminishing every year as I was getting more knowledgeable about things, but this year there was none.

That is not to say that there was no damage to the water line over the winter. There were two breaks to the line, both caused by falling trees.

With them repaired quickly from pipe inventory I bought a long time ago in anticipation that there would be ongoing maintenance and repair, I waited for the pipe cement to harden then switched the valves and can now just barely hear the whine of the water turbine in the distant background. One of my goals for this year is to make a properly massive turbine house to muffle the sound.

Interestingly, I had not missed the hydropower electricity at all as the solar panels were providing all I needed, including four hours on the power planer the other day.

I appreciate magnificent artistry regardless of the medium or context, and thanks to RichardB for forwarding this video of Romanian egg painting to me. I was spellbound.

http://www.selvedge.org/blog/?p=26947

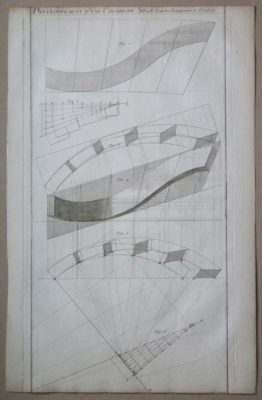

Today’s offering is another of Roubo’s many Valentine’s Cards to Geometry and layout, “How to Draw a Full-scale Pattern of the Curve of a Seat.” Without the use of digital calculators and computerized plotters it was necessary to compose an x-y exercise in order to obtain curvilinear shapes from which the patterns and templates for sinuous forms could be derived. Deriving the text for these plates was a bear, but the images themselves are elegant in a spare, modernist sorta way. I particularly enjoy seeing lines from the construct being shown outside the boundaries of the image.

The print has a crisp plate mark and is in excellent condition, with one very minor stain near the upper right corner, and was been removed from the First Edition bound volume with comparative care.

It was both drawn and engraved by Roubo.

If you have ever wanted to own a genuine piece of Rouboiana, this is your chance. I will be selling this print at Handworks on a first-come basis, with terms being cash, check, or Paypal if you have a smart phone and can do that at the time of the transaction.

$250

That’s one guy, two workbenches, in three days.

With Handworks barreling down the calendar at breakneck speed I knew I needed to get at least one workbench out to Amana since the space I would be occupying was just an empty square of real estate in the Festhalle. Plus I had lurking in the back of mind an observation and an unrelated goal.

The first was that the guys who came to the workbench-building workshop last fall found that the system for making the workbench allowed the legs to be installed after relocation home, and de-installed as needed. Second, I did want to make a workbench to donate to the Library of Congress rare book conservation group.

The self-evident answer was to make a couple of laminated Roubo benches. Simple, easy, and interruptible while in-progress. I had to do all the work around the other things going on on the homestead and in the shop, and in the end it took me about 15 hours working alone.

On Day One I spent the morning ripping a stack of 8-foot 2×12 SYP lumber into the pieces I needed for both the tops and legs. Normally I do not miss my 3hp Unisaw sitting in the basement of the barn, not yet wired into the electrical system, but this certainly was one of those times. My smallish 9-inch saw works for about 95% of my needs but this one was at the limit.

Since I now keep my rolling planer stand in the basement I loaded everything into the pickup and drove to the back side of the barn. I spent most of the afternoon planing all four sides of the lumber to remove the ripples from the industrial sawmill and get the lumber ready for gluing.

I loaded everything back into the truck and hauled it back up to the second (main) floor and brought it in.

A second set of hands would have definitely cut the time for these tasks by at least 1/3, but it was just me. On to the glue-up.

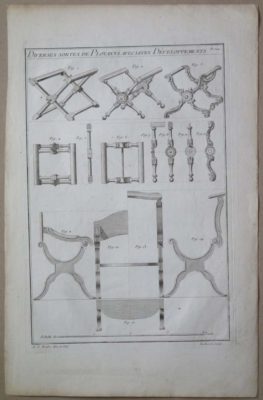

Today’s offering in the l’Art du Menuisier First Edition inventory I will have at Handworks 2017 is Plate 234, “The Manner of Determining the Desired Centers for All Kinds of Seats.”

In the days prior to CAD/CAM computer programs, i.e. 7th Grade Drafting Class with Mr. Teft for me, the ability to use geometric constructions to lay out your projects was integral to their fulfillment. Back in Roubo’s day this included intricate and sometimes arcane exercises of which Plate 234 is one. A cursory browse through the Book of Plates reveals that this was to Roubo what Price Theory is to me; something that keeps us awake at night and our brains perilously close to hyperdrive in contemplation; he included around five dozen of these exercises in l’Art du Menuisier.

The print has a crisp plate mark and is in excellent condition, notwithstanding a bit of a jagged left edge from the original assault of barbarism when extracting the page from the First Edition bound volume. It was both drawn and engraved by Roubo.

If you have ever wanted to own a genuine piece of Rouboiana, this is your chance. I will be selling this print at Handworks on a first-come basis, with terms being cash, check, or Paypal if you have a smart phone and can do that at the time of the transaction.

$250

Through my explorations of all things Henry O. Studley many mysteries have made themselves known, like details of his personal, financial, and craft life. Another one that I have made known as far and wide as I can has to do with the art form of piano-maker’s vises, which based on my observations are uniform in concept and performance but individual and slightly idiosyncratic in their construction details.

I am truly delighted to have contributed t the growing interest in the question and have been contacted many times over the past few years with folks regaling me with their own speculations and discoveries themselves. (Such contacts, if serious, are always welcome).

Here is one such communique from last week, which I present to you as completely as I can while respecting the privacy of the correspondent.

You may recall that a) we spoke briefly during your trip to New

England when you were researching vises, and b) that about a year and a

half ago, I found & acquired a piano maker’s bench in Worcester.

I have been rebuilding the bench, and writing about it on OWWM.org

I am aware, both through your work (book) and conversations with **** ******, that to date, none of the vises found have had any maker’s mark

on them. As I cleaned and repainted my vises, I did not find any such

marks either; only some numbers stamped on some of the parts. I had not

yet removed or cleaned the back plates, though, until this week.

The other day, while cleaning & measuring the plate for the front vise,

I found a number stamped on one long edge, & gave it little thought.

Yesterday, though, I was working with the tail vise plate, and out of

curiosity looked to see whether I’d find a number on that as well – and

instead, what I found was a maker’s mark! This was stamped along what

was the bottom edge of the plate, which was covered in rust, grime and

paint drips. I then checked the other edge of the other plate, and sure

enough, there it was, though this time it was on the top edge, and more

obscured by dents & dings, as well as the rust, etc.

The maker is J.S. Wheeler of Worcester, MA. Wheeler was a maker of

machinery, mostly for metal working, and was known for it’s metal

planers – which makes some sense, as we both have noted that these vises

were machined on planers.

Anyway, thought you’d like to know, and would love to hear your thoughts.

Tim

This is indeed exciting news to me, and revives my hope that more Studley-type information will continue to flow my way. On a related subject I got another recent email from a friend who was discussing the possibility of acquiring a reciprocal metal planer himself.

Finally I will note with a bit of irony that this growing body of information and an enthusiastic cadre of acquisition probably means the only way I will round out my set is to get off my kiester and get underway with making them with Jameel.

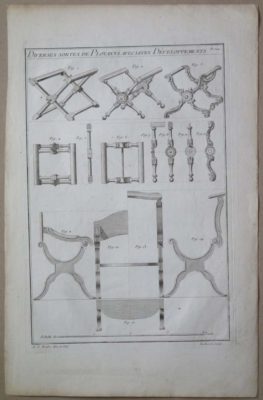

The next print in the l’Art du Menuisier First Edition inventory I will have at Handworks 2017 is Plate 224, “Many Types of Folding Stools and Their Development/Variations.” I find prints of this type to be particularly charming as the copper intaglio plate and the page were not aligned when they went through the roller press, resulting in an image that is askew. This phenomenon is not uncommon and gives further proof that this was a hand printed image on hand-made paper.

The print is in excellent condition. It was drawn by Roubo and engraved by artist Pierre-Gabriel Berthault, whose name appears frequently underneath the images of l’Art du Menuisier.

$300.

Recent Comments