With the young colt up on its not-at-all-wobbly feet I turned my attentions to completing the under-structure for the bench. This included three main elements, namely the backing board for the front apron (I knew that this bench was destined to be used against a wall and so would not need for both front and rear aprons to be used in work holding), the top batten nailer on the rear apron, and the top battens themselves.

While some folks are perfectly content with a single-thickness apron and top, I choose instead to make sure that these are double thick, or at least there are regions of double thickness, to better suffice for grabbing holdfasts which serve as the primary workholding tool on the bench. Thus the double-thick front apron and the battens-plus-planks for the top give me plenty of opportunity to locate and use holdfasts.

I ripped the front apron backer on the table saw such that the 2×12 became a 2×10 and a 2×1-1/2. I screwed these in place so that the top battens that rested on them were 1/8″ shy of the top of the front and rear aprons. This was so that I could plane off the top edges of the full aprons to remove the rounded mill-edge that they came with from the original manufacturing. I placed the battens roughly equidistant, beginning with the tops of the legs and interspersed in between.

Here you can see the front apron has been planed even with the top surface of the battens.

This portion of the project took a little more than an hour, so I was just barely past the three-hour mark on the project.

Up next – affixing the top planks and drilling the holdfast holes. Stay tuned.

The general approach to constructing a Nicholson Bench, an essentially “stick built” structure, is to assemble the legs into two end units and attach the aprons and top to them. This time I tried something a little different just to see how it worked. I assembled the legs to the aprons first, then added the end aprons to tie the four legs together. I found the approach neither more or less beneficial than the other.

As with any other project the first task is to start with a pile of lumber and make bigger pieces into smaller pieces. It was first thing in the morning so I was not up to full steam, and it took me about 45 minutes to get done. I chopped them to length with my circular saw and a framing square, and ripped the narrower pieces with the table saw. I ripped the boards in half, then ripped the factory edge to make sure everything was not only the same width but had a clean, sharp edge.

This project gave me the perfect opportunity to pull out my “butterfly sawhorse” as my assembly platform. I laid out the legs on the inner side of the aprons so that they were located such that the cross batten for the top (its location was determined by the top of the leg itself, the center picture is a close-up of the arrangement) was going to fall approx. 1/8″ below the rounded factory edge of the 2×12 apron, so that I could easily plane that edge square once the unit was up on its feet.

I used a drill driver for the decking screws that hold the unit together (the ultimate location for the bench did not mandate the use of period fastners) and with the front and back sections completed I was able to affix the end aprons for a complete outer frame of the bench in about 30 minutes. So, it went up on its feet for the first of several “up/downs” that were planned for the construction.

If you are counting, that means I went from pile of lumber to up on its feet in about an hour and fifteen minutes.

Up next – the front apron backer, rear nailer strip, and the cross battens for the top.

Recently I was contacted by Mike Podmaniczky, who I’ve know for more than three decades and who served un-knowingly as the prototype student when we designed the Furniture Conservation Training Program at the SI (Mike was in the first class of that graduated in 1990, I think) and went on to be a Furniture Conservator at Winterthur for many years. Mike and I shared many interests, not the least of which was the chairmaking of Samuel Gragg.

Fifteen years ago he curated a pretty darned wonderful exhibit on Gragg chairs and their making, and now as he is cleaning out the closets he asked me if I wanted one of the signs from the exhibit. My answer was of course, “Yes!”

It arrived recently and will be ensconced in the attic video studio alongside my Narayan Nayar portrait of the Studley Ensemble.

As we settle into the routine of life on the homestead it becomes ever more clear that it is always “firewood season.” We made it through the winter with a large amount left in the re-filled crib, having gone through the complete supply in the side crib and the front porch, refilling the former two months ago in case it was needed. It was not.

But still there are at least a half dozen large trees on the ground up in the woods, trees we felled last summer and simply awaiting my further ministrations. Now on nice days, and by that I mean “dry” days with good enough traction to get the truck up the mountain, I section and split a ton or two of firewood. I discovered a useful implement for the task, a ramp. I found that rolling the bolts of wood into the truck was dramatically preferable to hoisting them.

D’oh.

I enjoy reflecting on the fact that my goal of having two years’ worth of firewood ready to go at the beginning of winter might be fulfilled by autumn of this year. Plus, I am noting that late winter is the time to forage for firewood as the naturally fallen trees are so readily visible, as are ailing trees to be harvested this summer. I look forward to growing the pile to the size of a truck in the coming days.

Now, it only I could persuade Mrs. Barn of the need for a John Deere Gator or something similar. For the firewood. For the children.

Recently I was organizing/reorganizing my Japanese tools.

Apparently I am almost out of room for any more. But somehow I will find the space if I every get a Japanese marking gauge or a spear plane.

Last Sunday night we had torrential rains overnight, and this was the sight greeting me the next morning. The roar of the water was almost deafening, and we were hoping for a warm sunny day to help dry things out. It was not to be, as the day remained cold with snow flurries in the air all day long. There was no damage to the homestead, and the flow over the spillway ceased late in the afternoon.

The flurries kept up all night and in the morning there was a total of almost two inches on the cars.

Doggone winter is hanging on tenaciously.

Recently while en route to the SAPFM Tidewater Chapter meeting I stopped into a Michael’s store in search of one ingredient I wanted for my demonstration. They did not have what I wanted but as is my habit I took a stroll through the art supplies to see what might be on sale. My mouth probably fell open as I saw a deep discount on all their inventory of Robert Simmons Sapphire brushes, the sable/nylon blend bristles that for me are the standard by which all others were measured.

They did not have any 1″ brushes, but I bought all the 3/4″ flat wash and filbert mops they had. In doing so I added another half-dozen to my inventory (since I do so much teaching of finishing, I can never have enough good brushes), saving myself a ton of money. If I recall correctly these brushes are listed at about $70 apiece at retail, and I got these for about $10-12 each.

I do not know if this is a discount at Michael’s nationwide or if this was restricted to the one store I was at, but it would be worth your checking it out.

UPDATE: I’ve been to several Michael’s stores and found each of them to have the same discounted offer. They didn’t all have any inventory, but they all had the same discount.

With the writing box and drawer addressed and set aside it was time to move on to the fanciest work awaiting me. The veneering of the “legs” of the desk provided the showiest detailing for the entire project, and frankly consumed the most time and energy. Since I hope to continue building copies of this desk into the future it was worth spending the time to really get the process nailed. I got pretty close with this one after a considerable amount of prototyping.

As a recap, all of the materials for this project, including the veneers, were hand sawn and prepped. The highly figured veneers for the faces of the legs came from several crotch mahogany slabs I had obtained several years ago. In the meantime they had warped enough to make sawing them a challenge, and the exuberance of the grain made planing and prepping them a hassle. In the end I decided to leave the veneers ultra-thick and thin them once they were attached to the substrate.

As with all decorative pattern veneerwork the layout was the crucial thing. And, since the patterning for this project was almost exclusively circles and arcs my tool of choice would be based on a compass/divider, or in this particular case, a trammel set. Given the thickness of the veneers being cut for the pattern a stout cutting edge of the end of the trammel was called for. I first tried a utility/scalpel blade but it was not beefy enough. Ditto my LNT Latta cutter. After a fair bit of trial-and-error I settled on one of my striking knives and concocted a way to mount it to a trammel bar. This tool served to provide 99% of the work moving forward.

I mortised the trammel beam through the vertical block that would hold the striking knife/dovetail chisel and excavated the block such that the knife fit snugly, and attached it with hose clamps. Worked like a charm.

My first task was to true the outlines of the arcs on the legs. With my layout lines firmly established I taped a 1/8″ plywood square over the center point a struck the arc. This was a technique I used throughout the process.

I then cut the individual veneer elements themselves (sorry for the dearth on pictures, I was too busy working to take more). These were glued in place with hot animal hide glue.

Starting first with the central crotch veneer elements then wrapping up with the outer straight grain pieces cut to fit, the composition was completed. I have no idea why I left this camera in the center of the image.

This post does not fully convey the time consumed in this aspect for both the testing and execution, but it was many days worth of work (almost two months if the camera codes are to be believed) to get it to where I was not unhappy with the end result. After the veneers were all cut, applied, and trimmed, the full surface was toothed and scraped to a uniform thickness of approx. 1/16″. .

PS I have no idea why the final picture is rotated. It stubbornly resisted my efforts to present it otherwise.

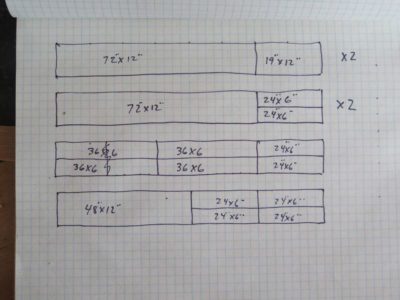

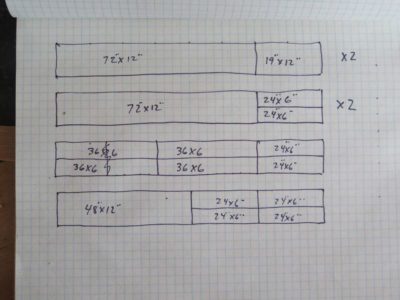

Since one of the goals for my Traditional Woodworking workshop in Arkansas this summer is to efficiently build a workbench for and by each participant, I actually did something I rarely do — make a cut list. Each workbench will consume six 8-foot 2x12s, and be accomplished in less than a day working in concert.

In case you are inclined to follow along and make one for yourself, here is a diagram of the cut list. Ideally the edge of each piece would have a crisp square edge, but since my big table saw is not yet set up I wound up planing them square ex poste and in situ part way through the construction. Each of the pieces ripped to “six-inches” is in reality simply the maximum width of a pair of boards you could render from the 2×12, so they turned out to be more like 5-5/8″ wide. Also, the 48″ x 12″ piece in the lower left corner should be ripped to approx 1-1/2″ and 10″, providing for a backing board for the front apron and a shelf nailer for the rear single-thickness apron, on which the top’s battens can be affixed.

After getting everything cut, the next step is to assemble the front and back halves, affix the ends, and incorporate the two 48″-long elements I just mentioned.

Stay tuned.

One of the exercises I incorporate into the syllabus for the Historic Finishing workshop is finishing a baluster spindle or two, to get the feel for brushing finish onto an undulating surface. Rather than spend a lot of time finding new ones for student use I just got a trash can full of them and recycle them as necessary. I found a very efficient way to strip them in preparing for the next round of use, a solution that I think would work for anyone who has a similar task.

I had our local welding shop to fabricate two vertical stripping tanks (for about $80), comprised of a piece of steel pipe welded to a steel plate base. One of my standing tanks uses a 2″ pipe, the other 2-1/2″. This allows me to use (and lose) a minimal amount of whatever solvent I am using, whether paint remover for the initial treatment of painted spindles or denatured alcohol for recycling the shellacked ones.

The system works like a charm, I just put the spindle in the pipe and fill it with solvent, then place a piece of metal plate on top to hold the spindle down and cap the cylinder, and in a few minutes I extract the stripped spindle, allow excess solvent to drip off, and wipe it down with paper towels It literally takes only 15-30 seconds of my time to get one done. Over a few days’ of doing this I lose only about a half-pint of solvent to evaporation, and whatever additional solvent is absorbed into the film.

Recent Comments