My reticence (inability) to discard wood even when others might see it as decrepit has once again come back to reward me.

The hefty vertical timber adjacent to the chimney had degraded to the point where it needed addressing and most likely replacement. Tim the restoration contractor really wanted to use a large hunk of vintage chestnut for the replacement, and low and behold I had exactly the piece he needed.

I had salvaged the chestnut posts from the lean-to of the lower log barn on the homestead when my brother and I replaced the aged and failing wasll structure with a new, built-in-place laminated post and beam wall two summers ago. The posts from the degraded wall were approximately ten inches in diameter and seven or eight feet in length. They weighed a ton.

I transported one of them up to the barn and started whacking on it with my 10-inch circular saw followed by a Japanese timber saw. In about an hour I had a piece useable to the restoration crew.

Tim said it was perfect, and after some additional fitting the new piece was inserted into the void left by the rotted old one.

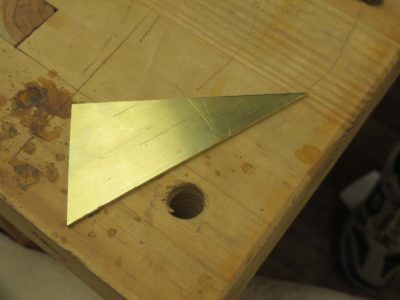

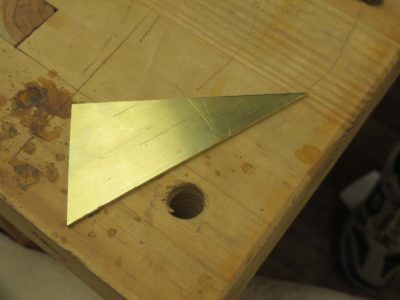

One of the tools emerging from the recent Making Roubo Squares workshop was a diminutive 30-60-90 triangle. This tool is integral to much of my/our shop life for areas ranging from cubic/pinwheel parquetry to laying out the dovetailed tenons of a Roubo bench leg-and-slab double mortise-and-tenon construction.

With the surplus rectangle of brass plate left over from the making of our nested set of cabinetmaker’s squares during the workshop there was plenty of brass plate left over for making other, smaller layout tools. Included in these were some small triangles that were roughly laid out with a plastic drafting triangle and rough cut on the bandsaw.

I took the opportunity to demonstrate the truing of the triangle to the workshop students, reminding them of the simple truths they learned decades ago in seventh grade Geometry class. Instead of using a micrometer or something similar to establish the tringle side lengths, a much easier, simpler, faster, and frankly more accurate method is only a compass or divider away.

After establishing the perfect square corner between the two shorter legs of the triangle it was possible to achieve a perfect set of 30-60 degree angles by using just a scrap piece of plywood, a pencil, and a set of dividers. For work like this I almost always revert to a pair of dividers from an antique navigational drafting set that I bought for practically nothing many years ago. These German Silver (alloy of brass plus nickel) tools are simply lovely and a pleasure to the eye and the hand.

First I traced the rough triangle onto a piece of scrap plywood, and set my dividers to the exact length of the shorter side adjacent to the right angle.

Then swinging the dividers to the hypotenuse I stepped off two of those lengths. If you will recall, for a perfect 30-60-90 triangle the hypotenuse is exactly two time longer than the shorter side of the right angle.

Once I determined that two-times-longer distance along the hypotenuse I re-set my dividers to this exact distance then transferred it to the longer side of the right angle, redrew the hypotenuse on the plywood, then transferred it to the brass.

Five minutes later I had cut and filed the new hypotenuse and had a perfect 30-60-90 triangle ready to braze on the foot and put to use in a multitude of applications.

All with zero measuring, although to be honest I did grab my dial caliper afterwards to check. I wound up being off by almost 0.002″ which probably amounts to a couple seconds or so of angle degree (or, about 1/1800th of a degree). I can live with that.

To quote my mentor in the pattern shop, John Kuzma (cleaned up considerably for a family-friendly venue), “Measuring is the enemy. Layout and transfer are your friends.”

I cannot recall my 7th grade Geometry teacher’s name but I do remember Mr. Fiske, who taught me Trigonometry in 11th grade almost fifty years ago. Together these men impressed on me the importance of triangles in every-day life. Thank you, gentlemen.

During the process of removing the ancient chinking and other fills on the log cabin, a disturbing find was a fist-sized hole on the north side wall. The hole was not necessarily a surprise as the north side was the most weather beaten with considerable surface lichens and some localized fungal rot, including some pretty substantial damage to some of the structure around the chimney (more about that next time). But the hole was concerning since it went all the way through the log!

After consulting with Tim, the owner of the log cabin restoration company, I decided to have him attempt the localized repair rather than cut out the whole log section or fill it with an epoxy-based composite. Tim thought he had just the right piece of weathered chestnut to make the fill, and the results confirmed his confidence in his skills and my confidence in him.

He had to excavate several inches on either side of the hole to get back to sound wood, and seeing the size of the pocket was a bit unnerving. But, the final results were indeed impressive.

A couple months of weathering and the fill will be invisible. Like I said, impressive.

By the start of the second day everyone’s trains were barreling down the tracks and all we had to do was keep on keeping on. Even as I entered the barn the sounds of sawing, filing, and sanding filled the air.

I had given each of the students one of these DARPA funded, MIT developed tools to work on the ogee tips at either end of the squares. One side was flat and the other was round, and when wrapped with sandpaper the tool was perfect for the task of finishing the shape. The uninitiated might think these were simply a 3/8″ dowel split in half on the bandsaw, but they would be properly ignorant of the national security dark technology pedigree of the tool.

Pretty soon the tips were more-or-less derived.

One procedure that was replicated perhaps a hundred times that day was returning to the abrasive covered granite blocks to bring the squares closer to “true,” a process that would be continued until after the torch work and the “square-ness” was perfected versus the Vesper final word square.

Len was the first to get the brilliant idea of creating a 30-60-90 triangle from the remaining scrap of rectangular brass plate left over from the four nested squares. Using my older version of the Knew Concepts Mark III saw he set to work and soon had the inside design cut out.

Meanwhile Dave, John and Pete got their tips shaped and polished.

Len finished the interior of the piercing of the triangle.

All the while the pile of brass filings and shavings built up at every work station. This continued until the very end and we compiled an impressive pile of scraps and waste filings, I’d estimate somewhere around five pounds worth.

All of this was prelude for the tasks presented after lunch as the shoes for the beams were brazed in place with silver containing solder. Once the mating surfaces were perfected it was time to move to the torch work stations.

The set-up was designed for efficient and safe torch work. I will blog about making a perfect set-up for bench top brazing in the next couple of weeks.

Fortunately I had all the things I needed on hand; fire bricks, kiln shelves to use as brazing platforms, and inexpensive lazy susan bearings so each place could turn. I placed three work stations on top of cement backer board from a home improvement center. For this project it was important to isolate the workpieces from the shelf and the bricks as much as possible to reduce the amount of heat loss from direct contact during the brazing. That is why the work pieces are raised up from the shelf by two small pieces of scrap brass.

After slathering on the flux to the contact edge of the square it was placed on the horizontally situated shoe, in the center. Then the torch was lit and the heat turned up. We were using both propane and MAPP torches, the first was fine and the second faster.

Once the assemblage was heated up and the brass began to get a coppery tone it was time to simply flow the coiled solder into the back side of the joint and let the heat draw it underneath the joint toward the flame.

Dave gave the quenched joint a fierce testing, and was impressed at the strength of it.

Then everyone set to brazing on the bases of their respective squares, then began the cleaning up process.

And that’s how we spent the rest of Day 2.

Just the sight of this brutal work made me all the more delighted that I passed the task on to other folks. With hammer and chisel and prybar the several hundred linear feet of concrete chinking was removed, along with the mesh lath and fiberglass insulation underneath. There was a mountain of debris at the end of every day, carefully collected and hauled off.

We had them start the project with this side of the cabin because this is where Mrs. Barn plants her pole beans, and we needed to get that done first.

After the joint void was cleaned and any decrepit wood was removed to leave a clean and sound substrate (there was a fair bit of this as the original chinking had not been relieved and the top of each course of chinking acted like a gutter, drawing in rain. Good thing the logs were old growth chestnut. It’s probably the only thing that saved them), the joint surfaces were saturated with borate solution to increase the rot resistance of the structure.

Though this description is brief I can attest to the scope of the work that took several days to accomplish.

Last week I hosted a workshop that reflected my peculiarities as a craftsman, a woodworker who loves metal work. Four skilled craftsmen, Dave, John, Len, and Pete joined me for three terrific days of fellowship and making. In this case making a nested set of Roubo-esque solid brass squares a la Plate 308, Figure 2.

The starting point for the three days was a 9″x12″x1/8″ brass plate.

Using my puny table saw and sled with a waste block to reduce the shrapnel, everyone cut a series of descending size squares.

After the table saw cuts, stopped to avoid over-cutting at the intersection of the inner edges, the cuts were finished with deep-throat fret saws and #6 jeweler’s blades which I provided. Pete had his wondrous Knew Concepts coping saw that worked like a charm.

And then the filing began. To protect the inner corner of the squares we ground off one edge of the mill files that everyone brought, starting with the disc sander followed by a diamond stone. This allowed for pretty aggressive work in the corners.

The filing was done on both inside corners of the cut squares and the outside corners of the remaining rectangles in preparation for cutting out the next smaller square, followed by truing on sandpaper over a granite block. (You can see the sublime Vesper square that was our “final word” truing reference for the workshop.)

This scene pretty much sums up the whole day. I was working right alongside the students making another set of the squares. I find this approach works best for the students to see me working on the same exact project, several times they came to look over my shoulder at some point in the day.

Before long everyone had their four rough squares ready for the next step, which was to trace and cut the offset/stepped ogees on each end. The small rectangle of brass remaining from the first four squares could be used later for a petite pair of squares and a couple of 30-60-90 triangles.

These were roughed out on the bandsaw, ready for filing the rest of the way.

That’s where we were at the end of the first day.

Stay tuned for Day 2.

During last week’s workshop Make A Set of Roubo Squares (more about that soon) one of the tools I used fairly regularly was this Roubo-esque and very stout exquisite palm-sized square. I vaguely recall it being in a box lot of stuff I bought at a Donnelly auction several years ago but that could be a false memory.

I have not been able to identify the tool maker but I do not consider myself to be well-versed in that world. The blade is stamped “Anderson” in script. It is a fine tool with a lot of heft, sitting in the apron pocket like a brick.

Anyone have an idea?

This year in addition to insulating the foundation walls of the cabin crawl space we decided to replace the ancient chinking between the massive chestnut logs of the cabin itself in order to make it more weather tight. We live in a fairly windy place and with the decrepit chinking in place there was often a brisk airflow through the cabin.

The first process was pressure cleaning the entire structure in order to identify the conditions underneath all the surface crud.

The size of that project was such that we contracted it out to a local log cabin restorer. If I had tried to do it myself it would have probably taken two years and eaten all of my free time. And made me grumpy since it would have kept me out of the shop most of that time.

Top to bottom all the stuff between the logs had to be removed with hammers and chisels. The crew cleaned the job site every evening, but the pile grew as each day went on.

It was fascinating to see between and behind the logs to the sub-wall of vertical boards on the inside. We found newspapers in there indicating that the inner sub-wall had been there since before WWI.

The scale of the project was indeed daunting. The old chinking and lath has to be chipped out, the underlying insulation and debris and, as Mrs. Barn called it, “the biosphere of the logs” (snakes, rodents, and a bazillion lady bug carcasses), cleaned out completely, followed by a multitude of steps following. All of this for the better part of a thousand linear feet of joint lines. That scale alone precluded me from undertaking the project, especially once you add to the equation the necessary scaffolding and equipment needed to execute the job efficiently and the few places of rotted or damaged wood that needed attention.

The north wall was in pretty tough shape and would need the most work. You can see a void from the rot big enough to put my entire fist through to the inner sub-wall.

Over the three weeks of the project there was a crew of stout lads here doing all the work. That made me smile. All I had to do was watch and sign the check.

Stay tuned.

For several months my broom maker has been up to his eyeballs in alligators as 1) his brooms have been selling like hotcakes and 2) he’s been finishing building their dream house on the family farm. As a result my inventory was low at first then gone altogether. Last week I got an infusion of polissoirs so I can now fill my back-orders, which will ship out tomorrow.

Some time way back I had my Browning shotgun leaning against the bench and much to my dismay it fell over, whacking into a stool in the way down and inducing a pretty severe bend one section of the gallery(?) running o top of the barrel (I am not 100% sure of this part’s name, I am not really a shotgun guy). The gauge of the metal that was bent is about 1.8″ x 1/4″ and the section about 3″ long. Although the shotgun still worked fine it looked pretty sketch with this damage. At the time I tried to un-bend the damage with opposing carpenter’s shims but the metal was too strong to budge.

Recently I tried a different tactic, instead using a half of a hardwood clothespin for the tapered wedge to drive between the barrel and the bent element and it worked like a charm. I first laid a piece of felt against the barrel to keep from scratching it, and gently drove in the tapered clothespin. It actually took some fairly robust whacks but eventually the gallery went back into place just fine with almost no noticeable permanent damage. If you look closely there is still a tiny bit of distortion but it does not shout at you from across the room like before.

Just another day at the barn. You can’t get much more low-tech than this.

Recent Comments