On Polishing Tortoiseshell

I have long held that tortoiseshell is one of the most fascinating non-shellac materials available to decorative artists. This South African silver and tortoiseshell writing box from the 1700s I saw in a Dutch museum some years ago is nothing short of captivating. Over the past decades I have developed an appreciation for not only the material but its use as veneer in historic furniture and decorative objects like pill boxes and tea caddies.

My interest is such that I even invented an imitation tortoiseshell that I use in my ongoing restoration of numerous artifacts. Here is a small gallery of some of my “tordonshell” examples. Attendees for my upcoming course “Introduction to Boullework” will get a chance to make some tordonshell for themselves (tentatively August 2014 — stay tuned).

Over the past few years I have been treating a collection of exquisite tortoiseshell objects belonging to a long-term client, mostly cleaning and polishing them along with the occasional in-depth repair of substantial deterioration. Recently while working on some beautiful little boxes I had time to consider the way in which many “restorers” and certainly dealers abuse tortoiseshell objects in their care.

The occasion of my contemplation was the hand-polishing of several small boxes, and the recollection of a conversation I had once with a dealer at an antique show. The artifacts for sale in his booth were nearly devoid of the surface character that should grace most tortoiseshell. In conversation he revealed with glee that he used power buffers to bring his pieces up to a kitschy glaring shine (my description, not his) turning gloriously fabricated items into something more akin to extruded or molded plastic from Target.

I would have gladly instructed this dealer on how I polish tortoiseshell (the right way), but after seeing what I have seen in numerous antiques shows, it would have no doubt been a wasted effort. But you gentle reader might be more fertile territory.

Here’s how I do it.

First, I gently clean the surface with lint free cotton cosmetics pads dampened with a few drops of naphtha to remove any greasy accretions from furniture polish concoctions. If the surface is especially grimy, I might mix up a water-in-oil emulsion, but that is a rare requirement. I avoid using other water based cleaners most of the time as the proteins comprising tortoiseshell are water sensitive. Probably not sensitive enough to be damaged by a quick and careful swabbing, but I avoid this virtually all of the time.

Next I move on to the actual polishing, which in this case requires the gentle application of powdered abrasives, the kinds used for preparing metallography specimens for analytical microscopy. I have long used 1 micron agglomerated micro-alumina abrasive from Beuhler, but there are no doubt other sources. I find that a thimble full would almost last for a life time. Not really, but I am still on the original stash of powdered polishes I have been using for decades (I have several grades for different kinds of polishing processes).

In some instances I place a little mineral spirits in the watch glass holding the powder and dip a piece of worn cotton flannel or felt block into the slurry to charge the pad, and gently but vigorously rub the tortoiseshell surface. Other times I drip some of the solvent onto the felt block and dip the moistened block into a container of the abrasive. Just as often once the pad or block is charged I simply use the pad or block dry.

In most cases the results are evident in a couple minutes of careful work on a very small area, and a small object takes an hour to carefully hand polish, more or less. It is important to avoid rubbing hard enough to heat the surface or erase the character of the tortoiseshell. This is where the power-polishers take a wrong turn. By buffing on a power wheel, they heat the shell and often deform it (the chemistry and properties of tortoiseshell are very similar to your fingernails, and are thus very sensitive to heat and moisture) and damage the shell, and polish away all the magnificent character of the material leaving it like gaudy synthetic plastic.

The ideal for cleaning and polishing tortoiseshell is to both recover the appropriate glossy aesthetic but retain the “water mark” moiré pattern inherent in the material.

Since tortoiseshell scutes, or plates, are formed in laminar depositions on the carapace of the sea turtle, when the material is processed in creating art, the layers of the deposition are cut through leaving a “Tide-line” pattern. When the shell has been very well preserved this pattern is nearly invisible to the untrained eye, but on appropriately aged shell it is well evident.

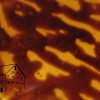

Thjis image demonstrates perfectly to progress of moving from a heavily oxidized and cloudy surface (bottom) to the glistening, beautifully nuanced texture of the finished surface (top).

The transformation of a properly polished object is dramatic.

My final step is the application of an archival maintenance surface, in this case a light coat of Mel’s Wax, a ultra-high performance easy-to-use maintenance coating invented in our labs during my previous employment (going into production and coming soon from the store at donsbarn.com) did the trick.

My process allows for the pleasing aesthetic result while preserving the appealing texture of the shell surface.

For more information about tortoiseshell artistry and technology check out my new book, to Make As Perfectly As Possible: Roubo On Marquetry, where Roubo expounds on the subject of Boullework and I add my own two cents. Also on my plate for the future is to write The Technology and Preservation of Ivory and Tortoiseshell, probably some time around 2015 or 2016.

I’ve read your comments on the cleaning of tortoiseshell and I’m wondering if you can offer me some guidance when it comes to cleaning the shell of an old tortoise from Madagascar. She was given to me by an uncle who was a captain on a Norwegian oil tanker during the early 1950s, was cared for by my grandparents until she died, and the shell was brought back by me to the US about twenty years ago (and almost landed me in prison for smuggling contraband). She appears to have been what is called a radiated tortoise. I have not touched it with any cleaners and am wondering how to best preserve it. She measured ca. 8×6 inches and has a little damage on one side. Any help you can offer would be very much apprciated. Thank you so much for your time.