Pursuit of the Ultimate Decorative Surface 2.2a

One of the great potentials about the interactions between human cultures is the transmission of aesthetic tastes. I cannot think of any such instance more important to historic furniture than the explorations of The Orient by adventurers from The Occident. All manner of images, arts, and decorations filtered into European tastes via journals and artifacts.

Among these artifacts were lacquered objects, sumptuously decorated with astonishing surfaces crafted from a varnish (and paint) refined from the sap of the poison sumac tree. Notwithstanding the dermatological implications of such a material, early attempts to import raw lacquer (urushi) were foiled by the drying mechanism of urushi, that being an enzyme induced chemical reaction that occurs in a warm, moist environment. Can you say, “A year in the cargo hold of a ship in the tropics?”

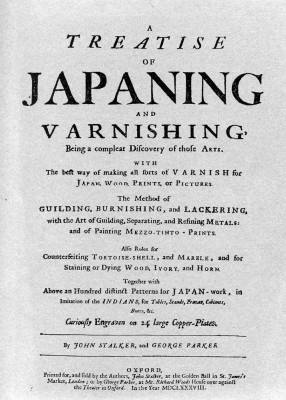

Oriental impact on Western decorative surfaces were codified as early as the late 17th century with Stalker and Parker’s Treatise on Japaning [sic] in 1688. Though a somewhat overheated booklet, whose two-fold purposes were, in my view, to state 1) how great Stalker and Parker’s products were, and 2) make the craft of japanning overly complicated thus scaring off potential competitors.

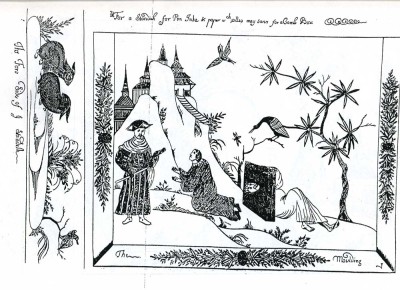

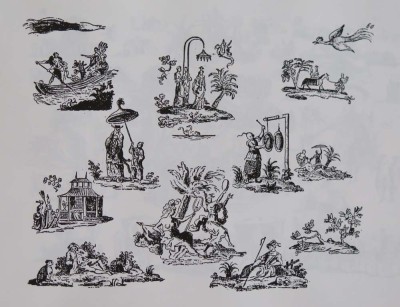

Nevertheless this slim volume, with its dozens of patterns to be copied by the decorative painters (remember what I said previously about the scarcity of artistic talent? Well, here’s how they dealt with it.) is an irreplaceable asset for anyone wishing to understand furniture decoration and artistry of centuries past.

Vast numbers of japanned pieces can trace their lineage to works like S&P, and decorations can often be seen on its pages. Given the passionate “sophistication” of cultural enthusiasms it is no surprise that multitudes of japanned artifacts were created during the era. The surprising thing might be that the era of japanning lasted well into the 19th century.

Japanning to me has all the hallmarks of greatness: aesthetically rewarding, with an orthodoxy but enough room for iconoclasm; technical complexity and wonderfully exploitative of material technology; and artistically challenging such that high skill was required even if artistic talent was not.

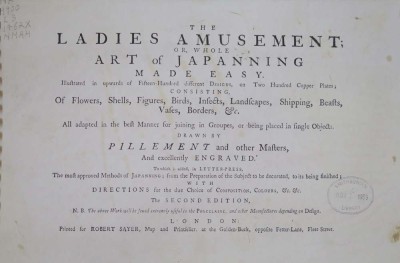

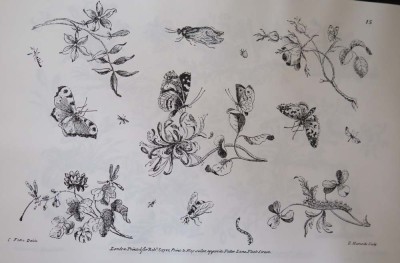

Stalker and Parker were only the first published popularizers of the art form. Another important volume was Robert Sayers’ oversized The Ladies Amusement c.1760, while dramatically lacking in any technical or craft information, was chock full of hundreds of patterns and images to be copied by japanners.

To be sure the dominant visual paradigm was Oriental, albeit often filtered through the lens of European sensibilities, much like much early porcelain portrayals of European iconography was filtered though the lens of Oriental eyes.

Whichever way you cut it, the resulting art is exquisite. My bucket list includes these two pieces, although I will opt for the much more stable plywood carcass rather than the solid lumber planking.

Join the Conversation!