photo courtesy of Narayan Nayar

Friday morning May 15, 2015, saw the fulfillment of a dream in such concrete and veristic terms that it was breathtaking. On that day and through the weekend, I was joined by about a thousand enthusiastic aficionados to share my interest (obsession?) with this over-the-top tool cabinet and its companion workbench.

The plan for the exhibit was for each visitor to have about 50 minutes in the gallery, along with a maximum of 49 other patrons. There were some pleasant surprises along the way, along with the need for constant reminders (mostly to me to keep on track as I could get too wrapped up in the story of Studley; throughout the weekend various docents had the task of pulling the plug on me).

photo courtesy of Naryan Nayar

photo courtesy of Bartee Lamar, I think

The visitors checked in at the ticket table, then waited in the elegant Library of the Scottish Rite Temple until their time to enter came to pass.

In the Library was a Lost Art Press station for the purchase of Virtuoso, although that was rendered inactive by the start of the second day as all the books available were sold. You can get a peek of MeganF right behind one of the delightful Bagby sisters (sorry, I simply cannot recall her name) near the center of the image as we are in the Library.

Also present was Narayan with his remarkable hand-processed print of the collection, which he printed himself on his large-format printer.

I met each hour’s group with some words of introduction and instruction (more of this function was inside the gallery as the weekend progressed) and then I made a point of attempting to greet and thank every single person at the door. I was and remain humbled and grateful for the enthusiastic validation they provided. In the picture above of the check-in table you can see me at the very back of the image shaking the hand of every person I could as they walked through the door into the gallery.

photo courtesy of Bartee Lamar

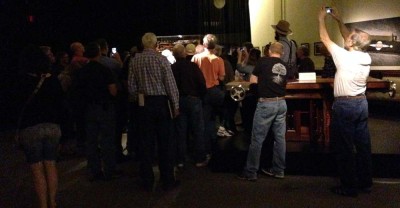

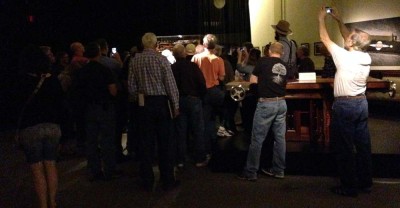

The visual of people engrossed and captivated by the three stations of the exhibit and the accompanying documentary video repeated itself every hour on the hour over the three days. I was especially delighted by the fellow who showed up ready to party with a head mounted digital camera to record the event. He sent me the video file and it was a gas!

One of my very favorite images was this one, with the ghostly pair of hands with a camera hovering above the case.

The hands-on replica bench top with its outfitting of period piano-maker’s vises and decorative elements from the tool cabinet was a big hit.

photo courtesy of Narayan Nayar

At the bottom of every hour we opened the vitrine and I spoke at some length about Studley and the tool cabinet and contents, and either opened or closed the compartments that lent themselves to that. This was the first time the guts of the cabinet were ever seen by the public.

After that we raised the house lights to provide the maximum lumens into the room for folks to take their final photos, including a lot of portraits and selfies with the case. The fellowship during these sessions was truly heartwarming, I only wish I could remember each interaction.

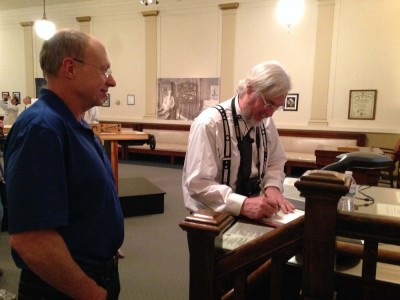

While that was going on, I moved to the back of the room where there was a line of folks waiting to get their books signed. I don’t know how many I signed, but it was a lot.

Friday was a bit different from the rest of the days as after hours Chris Schwarz and I were filmed by Charles Brock of the Highland Woodworker for an upcoming episode. I think the footage will be incorporated into the documentary film that Lost Art Press will be releasing in the fall.

One of the most surprising events of the weekend was one that did not happen. As I laid out the schedule for the weekend, I set aside a brief period at the end of every session to clean the plexiglass vitrine, wiping all the drool and nose prints off. It was unnecessary to plan in that manner. The audience was so respectful to the exhibit that the ongoing cleaning of it was essentially not needed. We wiped it off from a little dust and the occasional fingerprint, but y’all did great in the exhibit etiquette department.

The final afternoon of the exhibit was such a special time for me that it deserves its own post. Ditto the tale of The Heroes And Hired Guns. Stay tuned.

PS A number of these new friends sent me photos they took. I did not have access to all the emails when I wrote this and could not identify the photographer for each image, but you know who you are and I thank you sincerely for letting me use your pictures.

Since the vendors from Handworks were going to be, well, vending during the times the exhibit was open, the only way they could experience it for themselves was for me to arrange with Jameel for a “private” viewing outside normal business hours.

So I did.

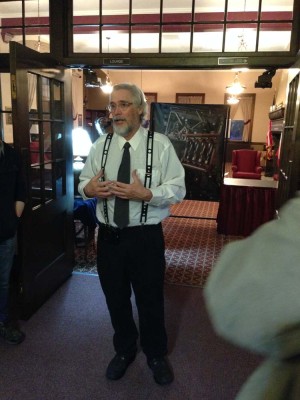

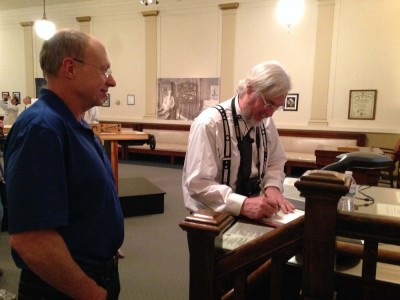

After the installation was complete we all hustled down to Amana for a quick bite to eat in the Festhalle Barn, then back to Cedar Rapids to get changed into the dress code for the weekend. Our attire was that worn by Henry in the only known image of him. Dark shoes, black pants, white shirts, and necktie, set off by a cotton shop apron.

In my case I dispensed with the apron and instead wore some of my self-made studelyesque suspenders I created especially for the event. Here I am with our delightful host, Douglas Heath, who was in charge of the Scottish Rite Temple facility. I think he had as much fun looking at the exhibit as any of the patrons.

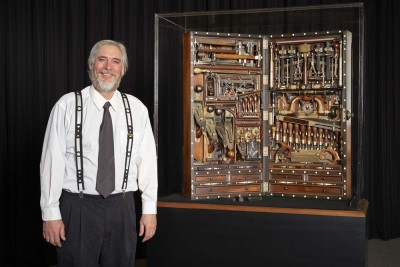

Narayan Nayar, the gifted photographer for the book, was on hand to take pictures of us with the exhibit before the hordes arrived.

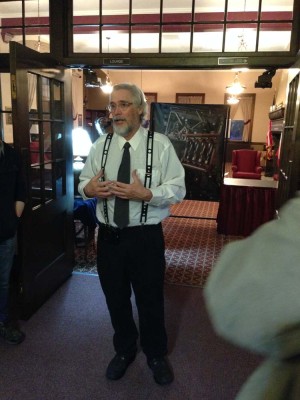

At the appointed time I went out to greet them, and my what a crowd it was! The entire lobby of the Scottish Rite Temple was packed.

After a few words from me we directed the folks into the hall. Unfortunately (?) I was kept pretty busy mingling and chatting, so all the pictures here are from the people who were there and took them, and are allowing me to share them with you. Thank you all.

The audience was rapt and enthusiastic. I actually did not stand near the case on purpose, I have seen it and would just take up space for those who wanted to get close. And yes, these tool makers wanted to get close!

One of my many enjoyable moments was crossing paths with Vic Tes0lin from the Lee Valley Tools Posse. About two months earlier, just as I was making my own suspenders, Vic wrote me a fan letter about the earlier iteration of the suspenders I had worn at Handworks in 2013. As a possessor of a mature physique, Vic said that he wore suspenders routinely and though the Studley version was great. Since I was already making three pairs of suspenders for myself, it was easy to just make it four pairs. Vic was near speechless when I gave him a pair, and he wore them proudly for the weekend and apparently ever since.

Many more pictures are bound to come my way, and if all goes well we will be building a gallery of photos over at the exhibit site.

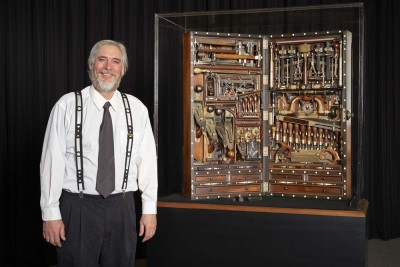

photo by Narayan Nayar

Just prior to the Thursday evening reception for the Handworks exhibitors, project photographer and my Virtuoso partner in crime Narayan Nayar set up to take portraits of each of the exhibit staff with the tool cabinet. I will post the images of the docents next week when I blog about their participation, but here is the one Narayan took of me of me.

This exhibit was the first time probably ever that I wore a dress shirt and necktie for four days in a row. My wife said it was the biggest smile she had seen on me for many, many moons.

As for the exhibit itself, the physical manifestation was exactly as I had envisioned it almost two years earlier. How many times does a person get to experience such a concrete realization of a dream?

It was not possible with my camera to get a true panorama of the gallery without it looking bug-eyed, so here are a group of images from which I hope you can derive the complete picture.

Last Thursday was spent setting up the show, or in the lexicon of museology, “installing the exhibit.” Several of the volunteer team for the exhibit had arrived the previous day and helped to unload both the dedicated fine arts transport truck and the cargo van I drove from The Barn. The remaining volunteers arrived through the morning and pitched in seamlessly. I will blog about these heroic volunteers next week.

The raucous good nature of the day was genuinely infectious and invigorating. There I was, watching the different continents of my life collide: friends from the museum world, an on-line restorer’s forum I have been with for many, many years, and the newer World of Schwarz. Not to fear, rather than volcanic activity as the tectonic plates collided, jocularity ensued. In a lot of respects it was just like our sessions in Studleyville where despite the grueling work there, Chris and Narayan and I spent just as much time laughing intensely, with sometimes ribald humor.

So while we started out that day with all the pieces of the puzzle I brought with me, the composition of the picture goes back a few days. The week prior I had spent several days in Cedar Rapids making sure everything was on track for the installation. Dedicated transport arrangements? Check. Host site? Check. Graphics? Check. Cabinetry? Check. Vitrine? Check. Lighting? Oh oh.

The lighting company was the last stop before departing for Studleyville, and it was clear immediately that there was trouble. Despite months of correspondence, in-person discussions, and repeated promises that, “Yes, 1) we know what you want and 2) we have what you need,” it was abundantly clear that 1) no they didn’t, and 2) no they didn’t. So I fired them and welked out the door with no lighting arrangements in hand. Frantically I called Jameel, who in short order found exactly the vendor for me. So, with less than a week before the exhibit opens — in other words, about two years behind schedule — the entire lighting scheme needed to be redesigned from a blank piece of paper. I did not sleep much that night, but by noon of the following day we had all the details worked out. I hit the road for Studleyville with a great sense of relief.

Six days later I returned with the exhibit in a box.

The first step in the installation was the receipt of the platforms and vitrine case. They were waiting for us when we arrived at the Scottish Rite Temple before 9AM. Those got hustled inside in short order. While a team of folks measured and laid out the room, the remaining volunteers carefully placed the exhibit furniture where I asked them. The layout resonated visually exactly as I had hoped.

At the same time the fellows from the graphics company arrived with the panels and banners for the exhibit.

Next came the unpacking of the Studley Collection. The packed tools were set on a work table for me to fill the tool cabinet later in the day. Each crate was re-closed exactly as they came apart. Losing pieces of the customized packing is not beneficial.

At the same time was the assembly of the base for the replica workbench top. Simultaneous with that was the placing and assembly of the vitrine case for the tool cabinet (see below).

The really heavy work came next, as around 500 pounds of cast iron was affixed to the approx. 250 pound replica top.

The photo of moving, flipping, and placing the elements of this ensemble was not taken as almost everyone in the room was doing lifting, flipping, moving, and exact placing of the multiple pieces.

First big piece down, two to go.

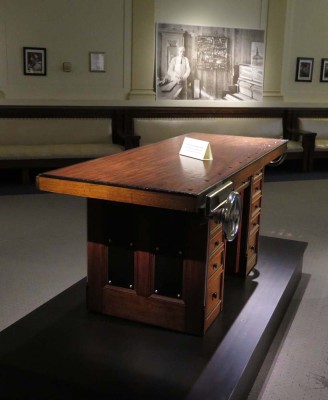

Next came placing the replica bench base for the original Studley bench top. This was not easy as the base was very heavy and the handholds few, but with care and muscle we got it done.

Yup, things were shaping up spatial composition-wise.

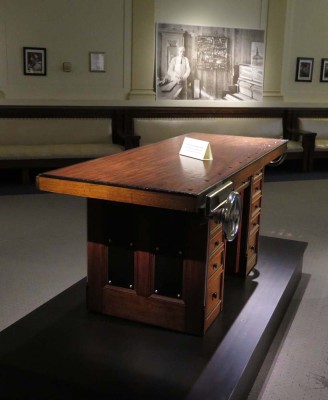

Up went Studley’s original bench top, on top of the replica base. O-o-o-oh yeah. We took a minute to stand back and admire our work.

At the other end of the room was the team joining the case and the vitrine. I had asked for a very snug fit, and boy did we get one.

It took almost everyone on the vitrine team to hang on to the top and press it down into the rabet of the base.

With a notable “thunk” it popped into place. Beeeyoooteeeful.

We were under some time pressure as we had to get the major elements of the exhibit in place before the lighting guys arrived, because they had to know where to point the lights. Makes sense, huh?

The bottom panel for the vitrine was cut, then lined with black felt for the plane underneath the tool cabinet. The fit had to be exact, and presented in such a way as to become completely unnoticeable once the exhibit was being viewed.

The lighting guys showed up exactly when they promised, with all the exact equipment they needed. What’s up with that? Just kidding. They were fabulous.

We killed the house lights and turned the guys loose.

The lighting units they had were slightly warm (2700K color temp) lithium battery light fixtures with magnetic bases, which the stuck on the ceiling fans!

Soon it was looking like an exhibit should.

Once the lighting was done, up went the black theatrical backdrop, setting off the entire space and establishing the respectful tone for the entire event.

I took a couple hours to load the tools in the cabinet, with the entire crew of volunteers watching with the same looks on their faces I would see throughout the weekend.

With several minutes to spare, were we done.

After almost a week of silence, due to my consuming activities with the life-changing dream-come-true HO Studley Tool Cabinet Exhibit, I am back on the, er, air? Over the next couple of weeks I will be reminiscing about the exhibit, but there is something you can help with.

I was sorta busy all the time since mid-week last, and actually managed to not photographically document my activities very well. Especially the public hours of the exhibit when I made over two dozen presentations to the roughly one thousand friends I was able to share it with. So, if you were there and have a *few* pictures you could share with me, please drop me a line here. Pictures of demonstrating the guts of the tool cabinet or of the docents interacting with with visitors or visitors studying the collection intently would be especially appreciated. Also pics of the LAP booth/tables where the book was sold, or where Jason was selling tickets and polissoirs at Handworks.

Your selfies? Not so much.

Stay tuned.

The materiel logistics for even a boutique exhibit (the term of art for the Studley Exhibit) is pretty staggering , when you consider moving supplies and collections from different places to a third place for the exhibit itself.

When you toss in the things needed for sales at Handworks, the piles of boxes get pretty intimidating.

First were the mounds of material for the exhibit and Handworks to be loaded and hauled from The Barn.

Then there was the Studley Collection itself, which was packed in subsets according to the location within the tool cabinet.

Each box was carefully loaded and bumpered into a larger crate.

The cabinet had a dedicated custom built case.

Then the crates were closed, and the work bench mounted and bound to its custom made cart, and the base was placed and secured on its custom made dolly.

Then loaded on the special truck, dedicated to the one-way transport to Cedar Rapids.

Double locked with a seal that would not be moved until I gave my permission at the end of the trip.

Rollin’ down the road, feelin’ fine.

Unloaded and safely ensconced in the exhibit hall, awaiting tomorrow’s installation.

With the exhibit of the Studley Tool Chest and Workbench only days away (May 15-17, 2015, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa), I find myself fielding a lot of similar questions (especially about tickets – if this is your inquiry READ THE LAST QUESTION) in email and conversations. So I took the time to create a Frequently Asked Questions compilation for the LAP blog, from which this was adapted..

How did the exhibit for the Studley Tool Chest come about?

Three years ago while studying the chest in person for the forthcoming book “Virtuoso,” I interviewed the owner for background material for the manuscript. At one point I asked, “Do you ever think about exhibiting the chest?” He smiled and just said, “I probably should, shouldn’t I?” A year later we spoke again and he agreed for me to do it.

Why is the exhibit in Cedar Rapids, Iowa?

For starters, one of the requirements by the owner was that the exhibit, “Be nowhere close to where I live.” Cedar Rapids fits that description pretty well. Plus, when I visited Jameel and Father John Abraham after Handworks in May 2013, we were just brainstorming and agreed that they needed to organize Handworks II, and having a Studley Exhibit in Cedar Rapids concurrent with Handworks II (only 20 miles away in the Amana Colonies) would be a great idea.

Did you consider any other site for the exhibit? I mean, I’d never even heard of Cedar Rapids before.

Originally I scouted out the Rural Masonic Lodge in Quincy, Mass., because it was the home Lodge to Henry O. Studley. I even visited there to explore the possibility. Four days later a catastrophic fire gutted the building, so that option was no longer on the table. The Scottish Rite Temple in Cedar Rapids is a spectacular site, and it will be the perfect venue. It was important to my vision to place the exhibit in an elegant Masonic building and one where the exhibit could be featured, not simply lost into a maze of a mega-programming institution. In the end I did not consider a huge city because I dislike cities. Well, I did think about Cincinnati, but is it really a city? Isn’t it more like a big town?

Why is the exhibit only three days long?

Much of that is simple practicality. My agreement with the chest’s owner requires me to be on-site with the exhibit all the time it is open to the public. Three days of the exhibit (plus at least three days of packing, shipping and installation on either side) was about all I think I could take. Besides, the host site is a busy place and I did not want to take a chance on not being able to have the exhibit there.

Are there any plans to extend the exhibit, or put it someplace closer to civilization if I can’t make it to Cedar Rapids for those three days?

No.

Why are tickets so expensive?

The answer is fairly straightforward. First, if you think the ticket price ($25) is high I guess you have never been to a good play or the ballet, or a ballgame (even minor league games cost more, once you factor in everything). Second, the ticket price is in fact a bare-bones reflection of the project’s budget. Feel free to price out the cost of a secured transport service to move around a collection like this, or the cost of insuring The Studley Tool Chest, or the fabrication of exhibit cases and platforms, or the rental and security of a prominent public building, or the theatrical lighting necessary… Best outcome? Every single ticket sells, and I will only be out almost a thousand hours donated for this labor of love. I would do this again in a heartbeat. Third, I wanted to make sure the visitor’s experience was amazing. Hence, the very few number of visitor slots.

What do you mean, “visitor experience” and “low visitor slots?”

My concept for this was to allow each visitor to get an in-depth exposure to the chest. So the exhibit will be quite spare, only four or five artifact stations, and each visitor will be in a 50-person group and spend 50 uninterrupted minutes with the exhibit. The docents and I will make sure everyone gets their turn to get as close as possible to the cabinet (about 4” to 6”). At the end of the 50 minutes each group will be ushered out and the Plexiglas vitrine housing the tool cabinet will be cleaned to remove any fingerprints, nose imprints and drool, so everything will be perfect for the next group.

Couldn’t you get some corporate sponsors to help cut the costs?

I did check into that, but the initial inquiries and responses led me to believe it was not a fruitful path. So I decided to take personal financial risk and pay for it entirely out of my own pocket.

So nobody is helping you?

A great many people have volunteered to help in ways large and small, serving as docents, packing and setup/take-down crews, etc. All tolled there are more than two dozen people involved, and are donating their time and (for the most part) their out-of-pocket expenses.

Will you be mailing me my tickets?

No. The ticket purchases are recorded electronically. I will print the entire list out, then check you off the list and hand you your timed ticket when you check in at the Scottish Rite Temple. You will show it at the door of the exhibit hall and be ushered in. Just to make sure, it would be a good idea to bring your PayPal receipt with you just in case we miss something.

I think my tracking down of literary shellac treasures is just like Indiana Jones’ quests for ancient artifactual treasures. Except without the alien and dangerous locales. Or the mega villains and the life threatening predicaments they inflict on the heroes. Or the femmes fatale.

Okay, it’s nothing like Indiana Jones. Well…, maybe a little like Indy’s adventures as this episode did involve traveling to a terrifying place, Hades-On-The-Hudson (cities absolutely creep me out, my temperament is much more suited to life in the boonies where my nearest permanent neighbor is a thousand yards away) and two lovely ladies instrumental in the discoveries. And there wasn’t really a mega villain, just a knuckleheaded academic, but then I repeat myself.

As my Shellac Archive grew into the thousands of pages it is now, it became clear that one of the brightest lights in the historic shellac research firmament was the Shellac Research Bureau of the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, New York. In the 1930s, as the winds of war for the survival of civilization began blowing, much of the research function of the venerable London Shellac Research Bureau migrated across the pond to our shores, to Brooklyn Poly. As a result, perhaps the golden-est epoch of subject research emerged as the research output of the SRB-PIB soon overshadowed the breadth and quality of almost anything ever produced by the LSRB or their Indian counterpart. As both of these enterprises were part and parcel of an imperial, ossified mercantilist/socialist system, when SRB relocated to a new culture – albeit struggling mostly due to the collectivist FDR regime in Washington – of innovation, risk, and accomplishment, perhaps the outcome was predictable.

At its peak just before and during the war, SRB’s group consisted of several faculty and several dozen students, all working on original basic and applied research under the direction of the renowned William Howlett Garner (let us pause for a moment of respectful silence. Okay, we can move on.)

Over the years I had acquired a number of the literary products from the group, mostly research monographs, but I knew from the few Annual Reports I had that my holdings that these monographs were but the tip of the iceberg. I could not help but wonder how much more there was, and began to follow up on this speculation. About 15 years ago I contacted Brooklyn Poly to see how much of the shellac research archive remained. It took many, many phone calls before I finally spoke with Heather, the research archive librarian for the university. And what an enriching experience our interactions were!

Heather was one of these classic cataloguers and retrievers of knowledge, and my inquiries into scholarship from three generations ago simply raised her estimation of me. Enthusiastically she embarked on her own journey of exploration with a promise to call me back.

And she did.

I knew immediately from the tone of her voice that the news was not promising. Deeply apologetic, she informed me the Shellac Research Bureau’s records were gone. All of them.

All of them.

Assembling the pieces of the story in retrospect revealed the utter shortsightedness of even institutions of scholarship in a culture with the attention span of a fruit fly. In the third and final installment of this tale of woe and reclamation, of knowledge lost, found, and shared, I reflect on the sentiments of the university’s Chemistry Department Chair (or perhaps it was Chemical Engineering) from the 1970s as the Institute was forming its new strategic vision, “Shellac? Who cares about that? The future is all about polymer synthesis! Throw all that old stuff away.”

Once the wax model is refined to an acceptable point the time has come to make the rubber mold for casting the replica. I simply lay the wax model down on a bed of sulfur-free plasticine clay, which is necessary to seal the back side of the model and prevent the rubber from seeping underneath when the rubber is poured in to make the mold. If it does seep in that is not the end of the world, it just makes more work in extracting the model and refining the rubber mold. What IS the end of the world for this process is to use any sulfur-containing modeling clay instead of the sulfur-free plasticine. The sulfur in the modeling clay inhibits the chemical reaction in vulcanizing the rubber mold, and in the end all you have is a gooey mess that never makes the transition from liquid to solid. Believe me, you do not want to enter this territory.

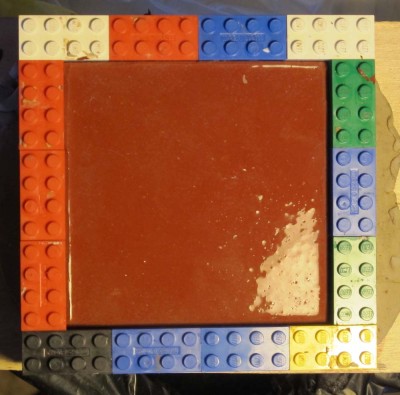

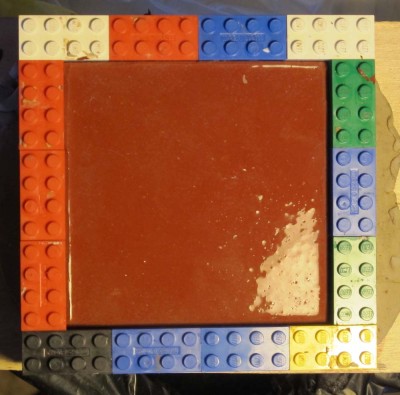

With the wax maquette set down on the plasticine, I build a dam around the space with Logo blocks or some analog. It is a simple and cheap way to enable a near infinite multitude of sizes and shapes for making molds.

Once everything is ready to go, I mix the silicone rubber and pour it in. For many years I have used products from Polytek; their prices are good, the product is good, but their customer service and technical help are stupendously great. Colleagues of mine are partial to Smooth-On products, and I have seen excellent results with their products but do not have personal experience with them.

I like to pour the liquid RTV silicone in a fairly thin stream from a foot or more in height. This breaks up almost all of the little bubbles that become included in the cup when stirring up the mixture, and bubbles are the enemy. By pouring in this manner, starting in one corner of the mold form and letting it flow over the model of its own accord, I find virtually all bubble problems disappear.

Once I have a rubber mold I find acceptable, and this often takes several generations of models and subsequent molds, I’m ready to cast a replica.

For these arches, I found that using West System epoxy worked just fine, and I mixed a paper cup with the resin and hardener, along with a dollup of black powder pigment to replicate the ebony of the original. I also dusted the surfaces of the mold with the same powdered pigment, to assure a “not glossy” final surface and to help reduce any surface bubbles, always an issue when casting heavy bodied resins.

For these arches I had the added element of including a pearl button in the element where Studley marked the center of the arch. I had the best luck with this in putting a drop of the resin in the recess then placing the button, using the liquid resin to hold the button in the correct place.

Having the button move while pouring the resin is a constant problem, I can only conclude that the specific gravity of the pearl button and the casting resin are similar, causing the button to “float” a bit after the resin is poured. Waiting a bit on the full pour after the button is placed and the resin begins to increase in viscosity helped but I am still wrestling with perfection on this one.

I take the raw casting out the following day, and smooth the back side on a flat plate with sandpaper, and the replica is done.

I prepared a panel with several of the decorative element replicas from the Studley Tool Cabinet (this picture is just a mock-up, the best castings were not yet ready when I took it), and if you make it to the exhibit next week you will get to handle that panel.

There are still plenty of tickets for Sunday afternoon especially, I think the remaining time slots are getting full or nearly so. If you are willing to hang around until Sunday afternoon, you might have a darned near private viewing.

See you next week.

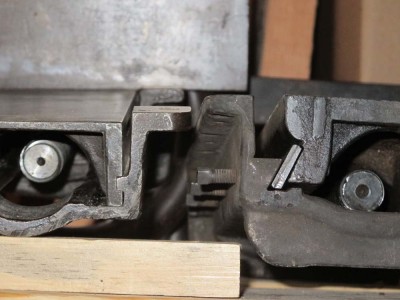

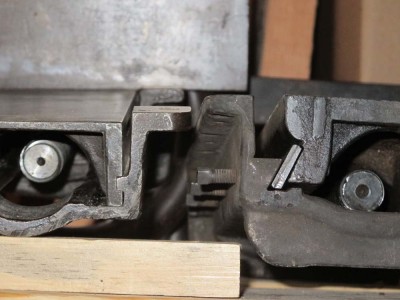

In preparing and packing the truck load of material traveling with me for the upcoming HO Studley exhibit, I was once again struck by the similarities and idiosyncrasies of the eight piano makers vices that will be on display there. What prompted my devolution into this indulgence of my vise vice was the adjacent proximity of Dan’s vise and Tim’s vise sitting on a wooden slab.

At first glance you might be forgiven for thinking these were two identical units, notwithstanding the dimensional differences. When they are turned over you begin to see some differences, but they still look like they are from the same lineage.

If you work up the strength to turn them around to look at more of the business end (Tim’s vise is about 60 pounds, Dan’s is almost 90), it is clearly apparent that there are some profound differences in the morphology of the frame-and-platen configurations.

On Tim’s vise, the ways are square-bottom channels with matching shapes on the platen. There is no adjusting these. Studley’s vises are of this configuration.

Dan’s ways are considerably different, again while providing the same tool functionality. In his case the ways are machined dovetails with on spaced to allow for the insertion of a pressure bar, which through the adjustment of square head gib screws determine the “tightness” of the unit.

And when you toss Mike’s vise into the mix, head scratching is the result, as the movable carriage is outside the frame that is fixed to the underside of the workbench. Where did that design come from?

Only one of the multitude of mysteries about these magnificent tools. I look forward to showing them to you at the end of next week.

Recent Comments