Yesterday brought the close of the Workshop Era at the Barn on White Run, due to my previously recounted business insurance cancellation. We had a grand time working in the world of historic finishing.

The students undertook my now pretty-much-locked-in-stone curriculum for the three-day class, a syllabus I settled on many years ago. It involved lots of surface preparation with pumice blocks and polissoirs, brushing shellac varnish, melting beeswax, scraping, pad polishing, rubbing out, and making some hand-made sandpaper.

I believe a good time was had by all, with much learning, fears overcome, and confidence instilled. The results are a feast for the senses.

I will be teaching the same workshop in a few weeks over in the Charlottesville area at Wood and Shop.

Here’s a quick reminder about the two upcoming workshops focusing on shellac and wax finishing.

The workshop at the barn (my final one here due to my already recounted business insurance termination) will be June 19-21. For that workshop contact me directly.

The identical workshop will be held at Joshua Farnsworth’s school/shop in Earlysville VA, July 17-19. Contact Joshua for registration and other information.

I hope to see you there.

It’s been a while so I thought I’d take a minute to catch up on the doings at donsbarn.com/shop, the product page of the undertaking (all of this — blog, writings, and store — are an amusement/ hobby).

I have enacted a slight increase on some of the pricing to reflect my increased costs for both the polissoirs but mostly for postage. Those changes are already now in place or will be very shortly. If these modest increases make my products un-sellable, that information feedback loop will be instructive to me to discontinue the enterprise. I hope that is not the case but the future will tell.

The product line itself will remain unchanged for the moment until I can get some new things finished (see below). NB: for those of you who care about and base your purchases on such things, my products are provided by hetero-normative cis-gendered folks of European ancestry and hillbilly inclinations; we use brown polyester or tan linen bindings on the polissoirs based on my original work with the Roubo translation project (I do not deal in the books themselves, you can get them directly from Lost Art Press), non-recycled paper and standard printer ink for the labels. I am resolutely idiosyncratic/redneckian in every aspect of my life, and if that disturbs you, well, I cannot fix that issue.

The beeswax is commercially obtained as raw wax (I’ve been told the slang term of art for what I buy is “slum gum”) which is then hand process purified. All the bees involved in the production are now dead; the bodies for a great many of them are part of the contaminant that must be removed. The shellac wax is obtained directly from a purifier in India. Mrs. Barn and I (42 years this summer!) do 100% of the wax product purifying, formulating and packaging. I have received several requests to create some paste waxes of differing formulations and I am doing some explorations of that.

I think I have solved the problem I was having with Mel’s Wax, the archival furniture care polish we invented at the Smithsonian (Mel was my friend and co-worker who is the patent holder), and that may be available for purchase in the immediate future. Stay tuned on that one. I still won’t ship it to California. At one time I thought it would be the cornerstone for my post-retirement activities, but it never caught on.

Until now the videos have been purchased wholesale from the folks who made them at Popular Woodworking, but they no longer produce physical DVDs. They are strictly a streaming platform from whom you can obtain the video directly. However, with their permission we will begin the production of the physical DVDs for sale and mailing. That endeavor is imminent, I just have to forward a couple of graphics files to Webmeister Tim who will be doing the actual DVD burning and packaging. Good thing on that as at the moment I am out of the Wood Finishing video.

Another video undertaking is to finally wrap up the editing of the “Make A Gragg Chair” video (I now know why there is an Academy Award for movie editing), and to finally get some videos up on a Youtube page. I have several, from presentations I have made over the years, and hope to begin shooting some less formal shop videos once I get a handle on the whole process with the help of videographer Chris, who is so busy I may have to execute the filming and production process without him. I am also working on a set of full-scale drawings of the chair for sale on the site.

If you come to Handworks please stop by to visit. The booth will have lots of stuff.

My compewder is working after a manner. But I am definitely in the market for a new one.

I’ve spent much of the past few weeks readying for tomorrow’s presentation at the SAPFM Mid-Year Annual Meeting in Fredericksburg VA. I’m now packing up everything and will hit the road shortly.

It’s all been about making sample boards based on the likely finishing resources available to colonial craftsmen, which by definition means it has been non-stop fun. The variety of finishes possible with a small menu of materials is astounding. Colophony, beeswax (shellac (of course), turpentine, whisky, naphtha, linseed oil, walnut oil, are all it takes for a party to break out.

How could anyone not love finishing?

One added benefit of the exercise is that I am getting re-enthused to knock out the book. It has been hanging over my head for far too long!

For the home stretch of the jam-packed three-day workshop the final set of exercises involved the giant panel. It had already served its first purpose, getting the students comfortable with laying down an exquisite brushed shellac surface over a large area. Since the panels were roughly half the size of a dining table, I’m thinking any hurdles of intimidation have been overcome.

At this point the panel was subdivided into four quadrants, each of them to be treated in a unique manner. The first quarter was easy — just leave it alone as an example of laying down an excellent base of three-inning shellac.

A second quarter was spirit varnish pad polished to a high sheen, demonstrating the option of creating a not-grain-filled padded surface.

The third quarter was hand polished with abrasive powders, first 4F pumice then rottenstone in mineral oil, using a polishing pad identical to the spirit varnishing pad. This was followed by a light application of paste wax and buffed when the wax was firm.

The final quarter was burnished with Liberon 0000 steel wool saturated with paste wax, and as with the rottenstone polishing, rubbed until you just get tired. When the paste wax was firm ex poste it was buffed with flannel to a brilliant glow.

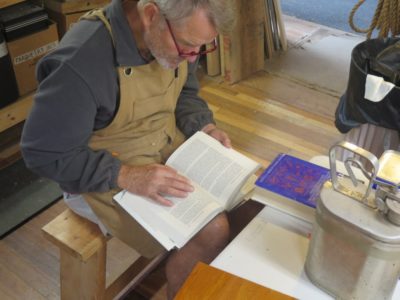

As always there is at least one somebody who gets seduced by my library.

When we wrapped up the event it was clear that they had all mastered the techniques wonderfully, and departed with confidence and a set of sample boards to guide and inspire them for decades to come.

If scheduling a workshop identical to the one these fellows completed, drop me a note. I will no longer “schedule” any workshops but only host them on request.

It was, in the unforgettable words of actor Pat Morita in The Karate Kid, “Wax on, wax off.” This time, however, the “wax on” was molten and the “wax off” was accomplished with Roubo-esque scrapers I made from brass bar stock and scraps of tropical hardwood flooring. By melting wax into the surface, the wood would be prepared perfectly for a grain-filled spirit-varnish finish in the traditional fashion, wax being the dominant grain filler until mineral deposits like plaster or gesso became more popular with industrial manufacturing of furniture. Although, when hammer veneering was the fabrication technique, the grain was well-filled with hot hide glue.

Three sample boards were readied for the exercise with pumice block and razor blade scraping, especially the crotch mahogany veneer panels that had a lot of residue from their original manufacture (I picked up a stack of these panels somewhere along the way and cannot say exactly how they were made except to say that the trace evidence suggests the use of phenolic adhesive and a mighty powerful press, but there was a lot of smoothing to be done). The mahogany panels were being prepped for primo pad polishing as was one of the nondescript sample boards, the third board was going to be waxed, buffed and nothing else.

With small tacking irons wax from the solid blocks was drizzled onto the wood surface, then the drips were re-melted and spread around the surface until there was a good deposition of the molten wax over the entire sample board.

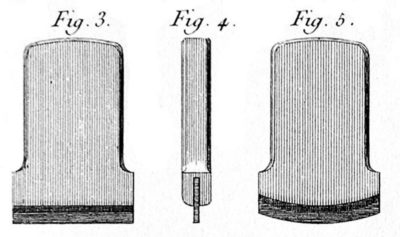

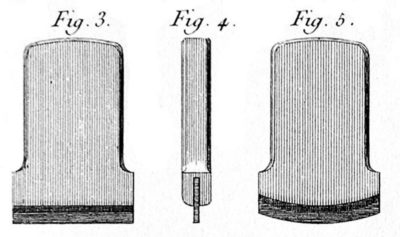

Once cooled, any excess wax was scraped off with a burr-less scraper fashioned after those described and illustrated by Roubo. When finished, it was time to move on to the process everyone had been waiting for.

The next world changer to emerge from the mists of the far distant past was to equip each student with a 1-inch polissoir and turn them loose burnishing the surface of smaller sample panels. The instructions were to press as hard as they could and rub with the grain until the entire board had an even sheen.

They did this to two panels; they set the first aside then scrubbed the second one with cold beeswax before wailing away on it with the polissoir, rubbing hard enough to turn the wax buttery and press it down into the grain interstices.

This was followed by second round of polissoir rubbing, followed by scraping off the excess and buffing out the final surface. Though this technique was often used simply for filling the grain, in this case I just had them remove the excess with a Roubo-esque scraper and then buff it out with a piece of linen.

Even this simple exercise resulted in the first of many sumptuous surfaces for the weekend.

It was lovely.

NB – This is not only my 1,500th(!) blog post over the past 8+ years, it is the longest one I’ve ever written. By far. Normally a post takes me from 30-90 minutes to create, occasionally longer or shorter. For this one, depending on your timekeeping system it took me a) four weeks, b) four months, c) four years, or d) four decades. So which one was it?

The correct answer is, “Yes.”

In order to tell this tale with some completeness I need to give you a tiny bit of background context. (In truth it turned out to be something more than a “tiny bit” but it is far less than a proper detailed exposition. I think that would be too much for 99.8% of you, and since I have about 300 readers that pretty much eliminates everybody — DCW)

To determine the cause of the soup-iness of the batch of Mel’s Wax, it should be the viscosity of a lotion and was instead the viscosity of heavy cream, I needed to go back to the beginning to reflect on the original concept for the formulation. This will be long and winding tale but provides the fullest possible explanation I am able to share about the reason for the batch “failure” (as I said earlier it was not really a failure, it was just not the precise outcome I had expected. In the end it turned out just fine.) I should probably break it up into three or four posts, but I decided to just put in one big steak rather than several smaller burgers. So, settle in with a snack and your preferred beverage for this ride. I don’t think you necessarily need to buckle up, but if a discussion of solvent thermodynamics gets you all worked up into a rave perhaps you need to restrain yourself as well.

BTW This post borrows heavily from the section that has been the bane for the past year of writing A Period Finisher’s Manual. And yes I have finally solved that particular puzzle and am back at work on APFM almost daily. Yup, it has taken me over a year to get a handle on one part of one chapter. Were it not so important to the craft of wood finishing I would not have bothered, but it is and I did.

From the beginning of our careers, even before we met and worked together, Mel and I formulated and mixed our own furniture maintenance polishes because we were not content with the products in the market. The commercially available products often used ingredients we knew a priori to be potentially deleterious to historic finishes, or used ingredients in proportions we thought were not optimal (for the furniture), or were simply too difficult to use.

So, the product Mel finally derived (I withdrew from direct participation fairly early for logistical reasons once we knew the development was on the right track; the easiest way for the project to move forward was for me as Mel’s Supervisor to assign him the task of taking it to fruition with me providing oversight and the occasional observation, review, or suggestion. Participating directly, as a Supervisor and programmatic manager [read: fiduciary] would have been an administrative nightmare) fulfilled splendidly our goals for “the ultimate furniture polish.” I do not believe it to overstate the case when I note that from a formulary’s perspective, it was balancing along a knife’s edge. That balance was lost minutely in mixing this batch of the polish, but that is all it took.

Here were the original goals, which Mel fulfilled brilliantly and deserves all of the credit and the Patents* that were issued.

- The end product was archivally stable.

- The product was chemically benign regarding historic finishes.

- The product was physically benign regarding historic finishes; the product was easy to apply and bring to a high sheen.

- The product was very high performance for both the presentation of the object and its ongoing maintenance.

- The product was easily removed with no damage to the surface from the removal process.

- The production of the polish did not require exotic technology

- The product was safe for the user.

These features are not independent variables per se, no component of any formulation or application is separated from the others, but they are different conceptually and thus I will provide exposition on each one.

Archivally Stable

“Archival” is at best a vague word without objective quantifiable meaning, but for the sake of this discussion simply use it to mean that some material or composition of materials does not degrade unacceptably fast and that any degradation by-products do not become manifest as pernicious actors in the realm of deterioration. That does not mean the word/concept has no utility when formulating a composition or even a practice. For Mel’s Wax the ingredients and their proportions/mixing were chosen with great care, and selected for long-term stability. This has pretty profound influence on the making and shelf-life of the product. Though the primary ingredients of Mel’s Wax (the waxes themselves) have a half-life that is near-infinite within the context of recorded human history, others were selected for the longest possible half-life, such as the exotic emulsifiers. And, the ingredients were selected with essentially zero cost consideration. Think about an old favorite like Murphy’s Oil Soap, which retails for a few dollars a quart. The emulsifiers used in Mel’s Wax, again, selected because of their stability vis-a-vie their degradation curve and chemical neutrality (see below) wholesales for *hundreds of dollars a liter.*

Chemically Benign to Historic Finishes

One of the truths of this particular cosmos is that the Law of Entropy cannot be repealed by even the most highly self-esteemed persons. “Ashes to ashes dust to dust” is not merely funereal homily, it is an inexorable reality in a cosmos governed by the laws of thermodynamics. So, as furniture finishes age they become closer to the “dirt” aspect of the verbiage just cited. As a practical matter this means that historic surfaces and finishes become more chemically imbalanced over time (usually due to UV damage or the imbibing of oxygen) and thus more susceptible to chemicals that impart damage because the chemicals deposited on the surfaces are thermodynamically similar to the surface and will thus impart undue harm to the said surface. This means that we have to maintain as close to a neutral balance or “polarity” for the chemical concoction being deposited on that surface. This, in turn, affects the choice of ingredients to be the most benign possible, which in turn influences the procedures for making Mel’s Wax. Those crazy expensive emulsifiers I mentioned earlier were selected specifically because they are less aggressive in creating the lotion-like polish, and thus less likely to inflict harm on chemically fragile surface. Further, the proportion of the emulsifiers in precisely calculated since excess emulsifier is a vector for accelerated chemical reactions, a/k/a “deterioration.” Also, the selection of the organic solvents used in creating the oil-and-water emulsion were selected for the maximum benign characteristics for aged surfaces.

Physically Benign to Historic Surfaces

There are some fine archival and chemically neutral furniture care polishes on the market in the form of paste waxes. Unfortunately many of these products require sometimes aggressive rubbing of the surface to bring their applications to a conclusion. Whenever you are faced with a physically delicate surface the last thing in the world you want to do is rub it hard to burnish the maintenance coating (paste wax). Given that reality based on what we knew it was pretty apparent that Mel’s Wax would need to be a creamy emulsion requiring very little physical impact on the surface for either application or completion.

High Performance

“High performance” is just another way of saying “It is physically robust and looks good.” It is and it does.

Easily Removable

For long term preservation and care considerations any museum artifact maintenance product must be removable with the minimal physical or chemical impact on the sometimes fragile underlying surface. Mel’s Wax was designed precisely to be removable with non-polar solvents and soft wipes like cotton swabs or lint-free felt.

Easily Produced

This was the point that precluded commercial-scale productions. It is very fussy to make, in fact my experience is that it would be difficult to make in anything larger than a five-gallon batch; I normally make Mel’s Wax just over a gallon at a time. The ingredients must be mixed precisely and with a fairly strict time frame. Further, the thermal ramping (the rate of heating up and cooling down) is a real stinker. Commercial enterprises, used to making home-care products in vats of several hundred gallons at a time, could simply not get it right. Many companies tried, including some you might recognize; they all failed. Instead the protocol Mel derived was a fussy micro-batch process that can go south with just a fraction of a percent of deviation. In that regard it failed the “easy to produce” goal.

Safe to Use

Not incidental to the formulation design is that the end product would not only be benign for the artifact, it would be (comparatively) benign for the user. Yes Mel’s Wax does contain organic solvents that are by definition deleterious to human consumption, but they are not acutely toxic compared to the overall landscape of industrial chemical engineering and formulation. Eating or drinking it would end you up in the emergency room rather than the morgue. As Dixie Lee Ray articulated in the Foreword to her brilliant book Trashing The Planet, under many situations di-hydrogen monoxide (water) is a lethal chemical. Like, for example, if you were to experience extended, intimate and excusive exposure for more than a couple minutes, e.g. unmitigated complete submersion. That would be a fatal incident.

Back to “The Cause”

This, my friends, is here the adventurous rabbit trail of solvent thermodynamics comes into play. As I mentioned earlier the formulation for Mels Wax was a razor’s-edge situation; if any component of the manufacturing was off by just a smidge, whether ingredient, proportion or process, the delicate balance of the formulation would be undone, or at least modified from where it was supposed to end up.

And that is what happened, but not in the way I was expecting. Solving the problem was an energizing exercise in synthetic thinking, combining the phenomenon (that which can be observed) with the noumenon (that which can be imagined).

When I was making this batch I was relying on my old faithful solvent, odorless mineral spirits, from the hardware store. There is nothing wrong with generic or even common ingredients like this provided they are the same thing from the manufacturer every time. I’d had great success with this particular solvent over the years. However, this time when I opened the container and decanted the necessary amount of the solvent into the weighing vessel (the formula is designed to assemble the ingredients by weight, not volume) the solvent coming out of the container was the consistency of chunky sour milk (fortunately it was odorless). Clearly some “shelf life” issue of the solvent and its plastic container was at work here. I tossed all of that and cleaned up to move on to the next gallon jug. Same thing. Repeat and rinse. Same thing. And with that I was out of my trusty tried and true odorless mineral spirits.

No big deal, I just picked up some new solvent, from the same company to (supposedly) the same manufacturing specs, and proceeded as normal. The solvent looked fine, the procedure went smoothly and I set about with other tasks until the polish gelled to the expected creamy lotion viscosity.

I came back in an hour and the polish had not gelled. No reason for hysteria, it as a very warm day and the thermal ramping was just being petulant. I came back in the morning and the gelling was still not to my satisfaction. Hmm, what was going on here? I even refrigerated one jar and it did not thicken to the desired viscosity.

At this point I stepped back from the entire episode for two weeks, just letting the stuff sit on the benchtop of the Waxerie while I cogitated. After those fourteen days I revisited the batch of the polish and noticed something peculiar — there was a stratum of pure solvent at the top of every jar. In a moment I knew what had happened.

The Crystal Set/Key-and-Lock Analogies – The Solubility Parameter

Have you ever wondered why substance A will dissolve in solvent X but not solvent Z? That question is perhaps one of the very most important questions in coatings technology and you would be wise to contemplate it. There is a real answer and I am going to tell it to you in a roundabout fashion. Hey, it’s my blog and I can tell the story any way I want. Hint -it all has to do with interatomic/intermolecular energy matching.

Stick with me now.

When I was a kid I got a crystal set radio, an earth-powered (actually it was the charge from the earth through the grounded radio chassis that made it work) primitive AM radio that allowed me to get the closest radio station to the house. I would spend many evenings listening to that local radio station, and after dark when the locals went off the air I could tune in the station from the next town over. Even though the crystal set had no power source I could listen to broadcast radio. Why? because the crystal of the crystal set allowed the unit to align, or match (receive), the frequency of the signal being broadcast with power being derived from the ground (I am not a radio engineer and did not stay in a Holiday Inn, so cut me some slack. I’m trying to explain a concept, not enter the debate about Marconi vs Tesla vs. Edison). Even with only the nearly unmeasurable electrons flowing through the crystal set it could “dissolve” the radio signals being broadcast because they were matched to each other.

Let me try another analogy.

Assume you come to visit me and my barn is locked (the punch line of my all time favorite joke is, “Assume a can opener.”). Not to worry, you’ve got the biggest honkin’ key known to man in your pocket and you go after the lock on my door. (I am assuming this action is done with my permission or you would have likely suffered a less beneficial outcome). Is this going to work, are you going to get in? Probably not. Why? Because the configuration (the energy) of the key does not match the configuration (the energy) of the tumblers in the lock.

And that my friends is why the polish was soupy. Let me explain.

The “solubility parameter” is the aggregate of (at least) three fractional components, which are in turn very specific intermolecular energy values. We use a graphical tool called the Teas Diagram to visually plot out the dissolving characteristics of both solvents and solutes, although this is an incomplete tool for selecting ingredients in a finish formulation. I discuss this at some length in A Period Finisher’s Manual.

The formula for Mel’s Wax depends on an organic solvent blend of a particular energy balance or “polarity” in order to walk the razor’s edge and fulfill all the preferences described above. To work perfectly the energy holding the solvent blend together (the key) had to match the energy holding the ingredients together (the lock) precisely — not perfectly — in order to accomplish the end point we wanted. My old dominant solvent had the exact correct energies to match the ingredients were were putting into solution in this particular operation. This phenomenon is called the “solubility parameter” as it is literally the aggregation of the interatomic and intermolecular electrical forces holding everything together, at least in the universe of solutes and solvents. Often it is reduce to the verbal shorthand of “like dissolves like.”

Yes, there are solvents for Mel’s Wax that could do the dissolving more efficiently than others. Solvent/solute compatibility is a range not a fixed point since no solute or solvent is 100% a pure single molecular content, and within one particular range we got the desired outcome. Was this solvent blend the “perfect” one to create the solution? No, because perfect solvation was not the preferred outcome since that “perfect” solvent blend would not fulfill the previously stated goals. For that we needed a milder (less polar) solvent blend. As I said the solubility parameter allows for a range of options to accomplish similar goals and characteristics.

Getting back to the original issue, why was this batch of polish soupy? Because even though the new solvent as ostensibly identical or similar to the previous solvent (it was similar but not identical) and still well within the “safe” range or creating our archival polish, it was just enough different as to perform more efficiently as a solvent. In short, each unit of solvent dissolved more of the polish ingredients than the previous solvent, so less of the new solvent was needed to accomplish the task of doing the dissolving. In a normal solvent/solute solution this is usually no big deal, the solution is just a tiny bit more diluted than would otherwise be expected. But, in a two phase system like an emulsion combining an oily fraction with a watery fraction even minute deviations can impart huge differences.

In the end, the polish was soupy because there was excess solvent that had nothing to do but sit around and be liquid adjacent to the two phase emulsion. Yes I could force it to go into the emulsion but it would not stay there. As I showed last time the performance of the polish was unaffected. It was just soupy, that’s all.

But I didn’t want soupy so stay tuned for the next episode of As The Polish Turns to see how I responded to the problem.

Normally at this point of the formulation the molten polish is an almost transparent amber liquid. It usually does not obtain this white-ish opacity until after it has been transferred into the jars and cooled for an hour or so, a little longer on a warm summer day.

With a recent batch of Mel’s Wax behaving oddly, becoming white-ish much earlier in the process than I have come to expect but nevertheless attaining the expected appearance when fully cooled. This batch remained almost fully liquid when it should have congealed into a soft lotion, and I set it aside for several days to cogitate over the cause(s).

Just to make sure I was not completely misguided I tested a bit of this liquid polish to judge its performance, and it did just just fine. So I did a contemplation deep dive to consider what might have “gone wrong.” In retrospect “gone wrong” was not the correct perspective, it had just developed differently than previous batches. But still, the question was “Why?” (A second question was, “Is this a new product?”)

When I returned to the jars after letting them sit undisturbed for a week I noticed an even more distinct stratification of the contents than had been suggested immediately after the making. In fact the top quarter inch of every jar was a near-pure fraction of solvent.

Using a disposable pipette I decanted the free solvent from the top of every jar, depositing the excess into a single large paper cup. According to my digital scale the contents in each jar included 20% excess solvent. Hmm.

Once the excess was removed the emulsion polish fraction underneath the solvent fraction was much more like the polish should be, and again performed precisely as it was supposed to. This observation made me reflect not only the original formulation from 15 years ago but also my materials used the previous week. It was a noumenological exercise, a/k/a “thought experiment,” that in the end bore great fruit.

Next time – The Cause.

Once apon a time I thought making and selling Mel’s Wax would be a foundational activity for me in “retirement.” I believed the product invented for the archival care of furniture and wooden artifacts while we were together at the Smithsonian would grow into a prominent role at The Barn (half of any proceeds go to Mel’s widow.) The custom-designed performance and formulation was unlike anything else available to furniture caretakers, and one major player in the home care products market whom we approached to manufacture it declared it to be (when cutting through the corporate-ese) “…the best product of its kind we have ever seen, but we have too much invested in our own brand to pursue it.”

Instead it has become a minor amusement for me as there seems to be little interest in the product. Admittedly this might be because I will not turn it over to some third party for production and marketing. It is a fussy product to make, and its applications may be too niche. We found that every potential producer who tried to make it cut corners and substituted more “convenient” ingredients (read: cheaper) or made other modifications to the formula and process to the disadvantage of the product concept and performance.

So, instead of working at anything near my capacity of a one-man shop, even if expanding that to a one-man-and-his-really-smart-wife, I find myself making batch (28 units) every so often. Last year while mail-order businesses boomed in general, I sold exactly 17 units. This year is better, having outsold 2020 by a factor of three already, so I was needing to make another batch last week, the third one this year! Normally I make it during the winter when things are cool in the shop (I keep it around 60) but we are now in the throes of a heat wave (low 80s).

While making the batch it seemed “off” and I set it aside for several days to settle down (sometimes it takes a while for the emulsion to fully set). When I checked back a week later it was still “off” (had not settled into the “lotion” viscosity) and I wondered if ambient heat was the issue. I’ve placed it in the basement of the barn (60 degrees) to set for a day or two and I will check it again. If I still do not like it I will make a whole new batch.

Aside from the digital analytical scales I use to get the ingredient proportions correct, the most important tool in the process is a laser thermometer. Ramping up the temperature and (as important, if not more so) ramping the temperature down is vital to making Mel’s Wax.

This episode not only made me go, “Hmmm,” but reminded me how finicky it is to make.

Recent Comments