It’s been quite a while since I 1) did any Boullework and 2) made a public presentation.

The last week or two I’ve been going through the exercises I’m demonstrating this coming Saturday to the SAPFM Blue Ridge Chapter, everything from making tordonshell to cutting some new Boullework panels.

When I assembled the metal and tordonshell packet and set about to sawing, the magic just wasn’t there. On a normal day once I get in the rhythm I can go for an hour or longer per saw bade, sometimes even half a day. But not this particular day. Sigh.

I was snapping blades like I was trying to break pasta. It took me four hours to saw a 1/2″ circle (and a pretty raggedy one at that) and I broke more than two dozen blades in the process. When I swept up the pile was truly impressive, but my camera was not handy.

Bad posture? Bad lot of blades? (it really does happen some time) Packet too thick? Rusty antiquated shoulder? Vision problems? (well, that is a given)

Some days are just like that. I’ll aim to get the bear tomorrow.

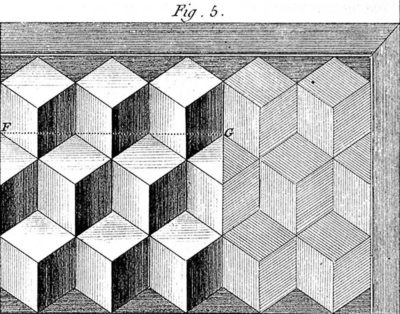

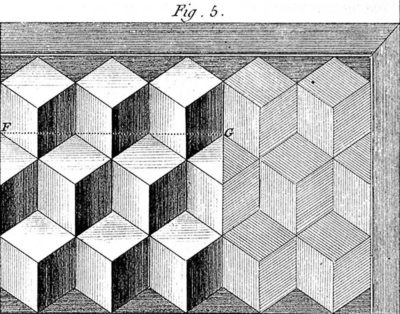

When discussing the layout of parquetry patterns, Roubo is adamant that the primary pattern must be either whole or half units of the geometric composition, that having a partial sequence of random width was low rent. With that in mind I began to layout the parquetry pattern I wanted for the shell of the tool cabinet.

Using the literal dimensions of the cabinet width I began the process by shooting some guide lines then stepping off the fragments of the design using my 30-60-90 triangle and a set of dividers.

A la Roubo, my exact measurement was unimportant. What was important was that a primary east-west composition turned out to be exactly X number of full units wide, with the adjacent rows above and below that main row would comprise of X-1 units terminated with two half units.

Once this was accomplished I was able to lay out the sub-units of the of each parallelogram in the Roentgenesque fashion I was shooting for.

Now it was time to begin sawing the requisite veneers from the blocks of Roubo-era oak scraps, and from them to create the diamond patterns to see if the composition worked as well in reality as it was looking inside my imagination.

Stay tuned.

I am delighted that in the aftermath of being disinvited from the Winterthur conference on marquetry, the Blue Ridge Chapter of SAPFM immediately extended the invitation for me to make my presentation to their group on May 21 in Fredericksburg VA, at Woodworkers Workshop, 1104 Summit Street. I will be the afternoon speaker/demonstrator. It’s my first traveling presentation in more than two years and I am looking forward to it.

You can get any particular information you need through the SAPFM.org website if you are interested in attending, or you can let me know and I will forward your interest to our Chapter Coordinator. I think there is a $10 fee to cover coffee and lunch.

In related news, I will be one of the presenters (Historic Finishing) at the SAPFM Mid-Year Conference, coincidentally also in Fredericksburg, June 26.

Over many years due to some fortuitous opportunities, including the generosity (?) of fellow woodworkers cleaning out their stashes of stuff, I have managed to acquire an awful lot of veneers. Those that are unusual or rare go one place in the barn, but the large majority is mundane and gets stacked on a pair of cot bases on the floor directly overhead of my studio space. There is nothing special about this pile of veneers other than the fact that for the most part this is vintage, heavier weight material than you would routinely find today. Most of it is in the range of 1/20″ to 1/30″, in poplar, walnut, maple, ash, cherry, and birch.

Even If I was manufacturing furniture, I would never use all this up.

So, what to do?

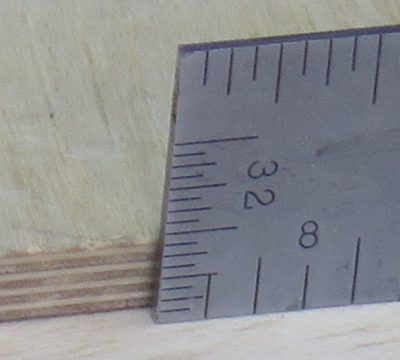

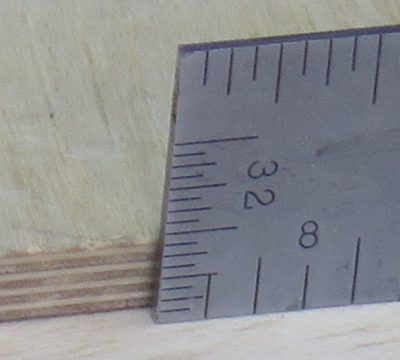

I’ve been contemplating making small, elegant boxes, mostly with either parquetry/marquetry or fuaxrushi presentation surfaces. Some of the boxes would be straightforward cubic shapes, others bombe’. What better foundation for these decorative techniques than ultra-high-quality veneer-core plywood? I have long believed that a static substrate of high-quality plywood is superior to a dynamic solid wood substrate with its inexorable rheological response to environmental moisture change. I could spend the big bucks to get marine or aircraft plywood, or I could just make my own.

So, I will. I have had excellent success in the past making small epoxy/veneer plywood panels for little projects and will now make that my SOP for fancy little jewel boxes. For larger pieces, say 12″ x 18″ or maybe a little larger, I will need to make a veneer press. For bombe’ panels I will need to construct forms and devise a vacuum press.

In the end, it is all just more fascinating stuff to do in the adventure that is life at the barn.

When it comes to large scale furniture making, or at least when there are large expanses of flat elements such as sides, doors and backs of larger cabinetry, one of the constant challenges to makers is adapting to the movement of wood through the seasons by means of various assemblages. Long ago I developed the attitude it would be more efficient and more successful to use wood re-formatted to simply not move in response to environmental moisture. In other words, to use good quality plywood. That might make me a heretic in the fine woodworking world, and I will give that accusation all the consideration it deserves.

Okay, I am done with that consideration. As pundit Mollie Hemingway once remarked, “My spiritual gift is not caring what you think about anything.” That pretty much summarizes my attitude towards plywood as a legitimate fine construction material.

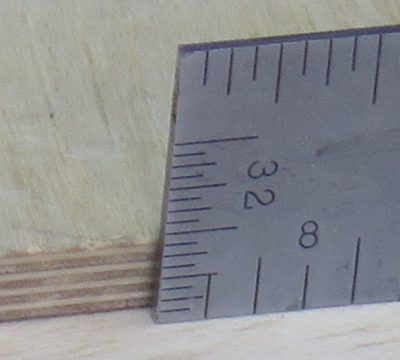

Frankly it is not a concern for most of my projects given the scale of my work. That said I have begun experimenting with home-made plywood even for some of my smaller work, consuming my copious inventory of veneers and marine epoxy to make nearly indestructible plywood like this. I will be blogging about this undertaking in the near future.

Sure, I know how to make frame-and-panel furniture and use it when it is stylistically appropriate, but otherwise I move on using good plywood for the panels of my projects. This becomes even more imperative for me when the ultimate purpose of the project is to express the decorative surface, either marquetry or japanning/fauxrushi. I just want the seasons to unfold with the carcass substrate not even noticing.

Over my 50 years of restoring and conserving ancient furniture I have seen far too many instances of a solid wood carcasses tearing apart the decorative surface to go down that road in my own work, as in this 19th Century French desk. Given the prominence of decorative veneerwork on my cabinet this phenomenon was one I did not seek to replicate.

This brings me to the construction choices for my tool cabinet, in some ways to be the culmination of my “making” undertakings. In point of fact this will be a huge (for me) simple box measuring roughly 48″ high x 42″ wide x 15″ deep. The cabinet has two purposes; 1) to hold as many woodworking tools as I can possibly cram in there on 12 (!) swinging panels, and 2) express the aesthetic of traditional Roubo/Roentgen parquetry (outside) combined with HO Studley’s inspirational aesthetic (inside). For this reason, I need a structure that is both robust and exceedingly stable if I want the cabinet to redound to my descendants. This pretty much means that I build the box and its doors out of Baltic birch plywood, for the most part 3/4″.

When you merge that preference with the additional facts that I am not set up to do large scale millwork combined with the ready availability of 24″ x 48″ “project panels” at the Big Blue Box store, my path forward was pretty self-evident.

Now the only real question is, “How many months with this adventure consume?”

Stay tuned to find out.

For many years I was/am a friend of Knew Concepts founder Lee Marshall and his collaborator and successor, Brian Meek. When we met at their first Woodworking in America conference they were just beginning to explore branching out from their world of jewelry-making tools into our world of coping and marquetry saws. I think those first interactions occurred around 2010 or thereabouts and I recall vividly an evening of dining and sketching on napkins as I proposed they undertake the design and manufacture of a vertical marquetry chevalet. Sure, this concept was revolutionary and heretical and might raise the hackles of horizontal-chevalet-traditionalists but that did not concern me nor apparently did it do anything but enhance Lee’s curiosity.

I had already made my first foray into the chevalet machine form with my c.2002 benchtop horizontal unit, but to be truthful I already had too much muscle memory dedicated to vertical sawing to ever feel fully comfortable with it. I always kept returning to my tried-and-true bird’s mouth and jeweler’s saw.

So my intersection with Knew Concepts crew was underway. Our ongoing collaborations led me to hold virtually all of Knew Concepts products in my workshop, trying out what they already were making along with many protypes in development.

I was very excited when they brought their first complete proof-of-concept prototype to WIA 2016 and gave it a good long test drive. There was much left to noodle out in the details but the overall concept was in place. Before those details were resolved Lee’s health declined to the point where he died, and Brian succeeded him at the helm of Knew Concepts. The transfer of the company was long and complicated, but eventually the new regime was in place.

Some time in 2019/2020(?) I dropped an email to Brian asking about the progress of the machine. He called me to say that one of the terms of the company transition was that at least one unit of the machine be manufactured and that unit would be sold to me. A few months later it arrived and I set it up just enough to give it a look-see. It is a spectacular machine and as of last month is now permanently ensconced at the end of the third daughter, ready to make marquetry at a moment’s notice.

While I was at it, I made a major improvement to my Knew Concepts Mark I jeweler’s bench saw by adding an oversized working platform, making it all the more amenable to marquetry than it was before, not surprising since it was designed for jewelry-scale work.

This post might be a long-winded way to say that I have loved marquetry since I first encountered it almost fifty years ago and now have the time and tools to make it an integral part of projects. I suspect my main emphasis will be parquetry, not curvilinear marquetry, but I am now outfitted for either or both. My tool cabinet will be my first big foray into monumental scale work as the outside will be vaguely inspired by the works of Abraham and David Roentgen.

I’m thinking this might be the conclusion of this Winter Projects series and it is time to return to our irregularly scheduled programming.

Stay tuned.

No, I have not forgotten the Ultimate Portable Workbench and will return to it very soon, but last week I spent a day resolving one of my frustrations with the massive oak Roubo bench. Until now I have just had open storge underneath it, and even though I put contents in boxes and milk crates it was not a particularly useful setup. Given my intention to reorient priorities in the shop and gather all my marquetry tools into one place, now was the time to make a change.

Way back in time I acquired a large number of drawers from surplused (read: thrown away) museum collection storage cabinets and have used them variously as cabinets themselves with a piano hinge, parts trays, etc. In this instance I tossed together a cabinet box into which I could place five 24″ deep x 36″ wide drawers to hold marquetry and parquetry tools and jigs. It was nothing special, just Baltic birch sheet stock and aluminum angle drawer supports.

I am pleased with the new accessory for the bench and shop and await my own decision on drawer pulls to complete the project. Sometimes I am a fussy client.

My friend Tom standing in front of Walt’s tool cabinet when we were visiting him in Staunton. I very much like this style of standing tool storage.

For a variety of reasons – desire to consolidate my core tools into a compact-ish volume in preparation for the “some day” time when I do not have a 7,000 s.f. barn, organizational order (my friends are laughing out loud right about now); work flow; parquetarian/channeling-Studley indulgence; antipathy for floor level tool chests — I plan to spend a good part of the next two (?) years constructing, decorating and outfitting a large standing tool cabinet in my studio. It will reside in the space currently dedicated to my saw rack and whatever is on the floor underneath it. I was really impressed by my acquaintance Walt’s cabinet and plan to use his as an inspiration for mine.

Rather than making it out of solid lumber with dovetailed corners my plan is to construct the box/doors entirely from 3/4″ & 1/2″ Baltic-birch plywood and sheathed in a yet-undetermined parquetry pattern (a la Roentgen?) using veneers sawn from leftover FORP workbench scraps. This project has been gestating long enough that I scrounged scrap 18th century French oak from the original Roubo bench-building workshop in Georgia.

The cabinet box will be roughly 48″ high x 42″ wide x 16″ deep with an open space between the base structure large enough to fit my Japanese tool chest.

Leave it to me to attempt a masterpiece project that almost nobody will ever see.

So, I’ve got this ancient 1930s era scroll/jigsaw, a Boice Crane Model 900. It is to my mind the tool form against which all others are measured. Acquiring it was my introduction to Tall Tom, my woodworking pal of lo these many years. He was at a community yard sale selling tools and carved walking sticks and had a small vintage Delta scroll saw at his booth. I checked it out and decided to pick it up on my return trip after browsing the yard.

It was, of course, gone when I did return. I engaged the seller (Tom) in conversation. He mentioned that he had another one back at the shop but it was too heavy to haul to a flea market, so we arranged for me to come see it at his shop. In the end we agreed to a trade; I would give him some turning lessons and he would give me the scroll saw. Little did I know that for many years I would be found in his shop on Wednesday evenings, and that he would make several trips with me to the barn (the picture is from 2011).

I am determined to get this saw rejuvenated and outfitted for marquetry work. Since I have a large wooden wheel I made for a treadle lathe, why not combine the two and make the Boice Crane something akin to a Barnes Velocipede Saw on steroids? If it works out it would be a superb marquetry saw.

So that is what I will try to do.

… to prepare for.

This week I was formally disinvited from presenting at the Winterthur marquetry conference this upcoming April, so those scores of hours over winter I had budgeted for creating my Boullework demonstration and writing the subsequent book chapter has now been cleared from my schedule.

As I was chatting recently with a woodworking friend about my presentation at the conference, he asked, “Do they know about your attitude regarding Covid protocols?” Gobsmacked, it had never occurred to me. Given our daily lives in the least populous county east of The Mississippi, it is simply not a common part of the conversation for people with whom I associate. Yes, Covid is a real pathogen and yes it has impacted our community (many, if not most, of the people I know here have had it), but we live our lives normally without disruption and do not obsess about it. I realized I should extend the courtesy of informing the conference organizers explicitly of my position, which I did in unambiguous terms.

Our county has been de facto mask-free for 18 months with numerous public gatherings like concerts, civic commemorations, seminars, etc., aside from some of the “larger” businesses like our local banks, the courthouse, school, and the medical center (the only entity for which masking makes a lick of sense). We talk face-to-face, we shake hands and hug, we dine together in homes and restaurants, we conduct business with each other as normal.

Our church suspended worship for a month in early 2020 then resumed worship and encouraged masking for another few weeks, but has met continuously since last Spring with all protocols being voluntary. Has there been Covid in our congregation? Certainly there has but everyone has recovered nicely, even our pastor who became the most gravely ill of the cases in the county to that point. Ditto every other church in the county (the Mennonite Church has exactly two adults who have not had Covid). Even the banks do not require masks for customers, only the staff are wearing them, which creates an exceedingly off-putting atmosphere. We have had hundreds of cases in our county of 2100 people, but only two “Covid deaths,” both of whom for which the pathogen was merely the final straw for exceedingly compromised personal health.

In short, I informed the Winterthur marquetry conference organizers that I have not and would not be getting any of the experimental gene therapy injections, nor would I wear a mask while in attendance at the conference. If they were fine with that, great. If not, well, “Houston, we have a problem.”

Houston had a problem.

The host institution would not allow me to attend under those terms, so I will not. I have my views and they have their rules, and apparently never the twain shall meet. I certainly bear no ill will and hope the conference is a resounding success! If it is live-streamed I will probably check into the proceedings.

An unexpected batch of time cleared? Check.

Recent Comments