In the finishing trade we often quip that our job is to make wood, “Brown and shiney.” Historically one of the main methods employed for the “brown” part was asphaltum, or tar. I knew of using tar as a toning glaze in gilding, where the tar would be diluted with white spirits and used to accentuate the gilded surfaces. I had not used it for wood until about fifteen years ago, responding to the evangelism of Alan Noel, a/k/a “The Czar of Tar,” and famed Atlanta based finisher and restorer and long time friend

For the workshop I’d asked Knoxville Dave to provide instruction on both pad polishing and asphaltum glazing, since he does so much more of that than I do. Yes indeed, that is a can of fiberless parging asphalt that he is mixing and diluting to glaze consistency.

We both using glazing as our “go to” technique for coloring, since it is so much more controllable than any penetrating colorant, and can be controlled to perfection. Sometimes staining works perfectly, but is is “just off a little bit” enough to take that technique off the table for me.

The exercise that really showcases the asphalt glazing technique was toning the turnings. They were first shellacked then burnished, leaving a magnificent foundation on to which you lay the color. The dilute asphalt was spread on the surface, then manipulated with cloth pads and fine bristle brushes to provided subtle shading to the presentation surface.

One of the beauties of asphaltum is that it performs almost like a dye, yet can be manipulated to provide both understated and exuberant change.

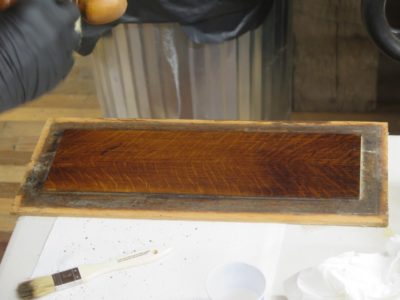

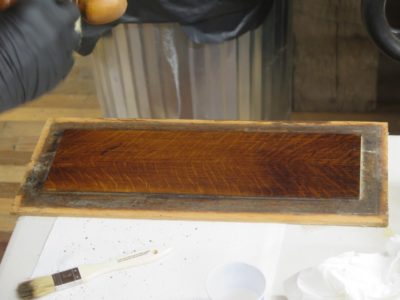

Dave also demonstrated using the glaze on a flat panel to great effect, mimicking the “ammonia fuming” so prized in Craftsman furniture finishes.

With that, the students were turned loose on the workpieces.

One of the fellows did some asphalt glazing to his new carved Bible box to great effect.

After the asphalt dried the surfaces were sealed with another coat of the shellac varnish.

The only thing left for the workshop was final detailing for the mega panel. Stay tuned.

One area of great frustration, fear and failure for many woodworkers is the challenge of applying a hand-finish to voluptuous surfaces, including carved and turned objects. While I could not provide a syllabus with examples of every possible option in this exercise I was able to introduce the principles, practices and tools requisite for the task. The key to success in varnishing the curvey parts is to use the correct tool, in this case an oval wash or Filbert Mop brush for watercolor paintings.

There are many excellent brands of watercolor brushes for artists that work brilliantly for wood finishing, but I have sorta settled on Simmons brushes in part because they were widely available at Michael’s. Even their cheapest brush, the “Simply Simmons” line, can provide an exquisite brushed surface. I have a few of the middle-quality brushes, the Simmons Sienna line, and they are even better. Of the premier line, the Simmons Sapphire, I have about a half dozen, and they are sublime, a blend of nylon fibers and sable bristles.

Regardless of which one you choose, and the price range is around $10-15 for the Simply Simmons to $75-100 for the Sapphire, you will have excellent results on undulating surfaces because the Oval Wash/Filbert Mop configuration does not have the square corner typical for most brushes. Those corners are the source of nothing but headaches on the carved or turned surface as it is the corners that “squeegee” off excess varnish, leading to the runs, drips, and errors that are the curse from finishing with the wrong tool.

In this workshop I had a pile of turned spindles and frame-and-panel cabinet doors to provide the battleground for the exercises. As almost always the starting point is to burnish the entire surface with a polissoir, and I have designed a “Carver’s Model” polissoir with 3/4″ bristles for just this instance.

One of the real delights for the workshop was that one of the students had just made a carved Bible box the week before, and brought it along for the class.

The transformation of the raw carved surface by the application of a few minutes’ worth of burnishing was truly astounding.

Then it was time to get to brushing the shellac varnish, and the draping character of the oval brushes – almost literally clinging to the irregular surface – was life-changing to the students as they were able to lay down multiple flawless applications of varnish.

Suddenly, what had been an aspect of wood finishing imparting fear and loathing became something to anticipate with celebration.

The third inning for the big board exercise was perhaps the simplest and certainly is receiving the sparsest treatment on the blog.

The preparation for the third application set was to scrape the entire surface briefly with disposable razor blades. Scraping finishes is a long standing tradition going back probably three centuries, but rather than go through the practice of preparing and using burr-edge scrapers it was just easier to use razor blades for such a limited time.

Following the scraping to the point where the surface was uniformly matte, the final application set was accomplished with another 4-6 complete coats of the ~2-pound shellac varnish.

The board was then set aside for the rest of the second day, to be used for the rub-out exercises on the afternoon of the final day.

In the realm of wood finishing there is probably no technique more revered than that of the mirror-like French Polish. The catechism, liturgy and mysticism of this top-of-the-food-chain practice form the transcendent popular doctrine of the art form. In roughly 100% of the finishing workshops I’ve taught over the past four decades my exhortations on the strategy and structure of finishing success are politely entertained, but the student response tells me that what they really want to know is “how to French Polish.”

Such was once again the case in the recent workshop. Inasmuch as “French Polishing” is not a direct manifestation of The Divine I am not particularly seduced by this mindset. Pad polished spirit varnish surfaces are indeed spectacular and lovely in the right setting, but I see the world of wood finishes as being so much larger and richer than that. Nevertheless a spirit varnish pad polish is one important component of the art, a practice I undertake on occasion and with pretty solid competence. Given that my pal Knoxville Dave does more of it these days than I do, I asked him to come to the barn for the weekend and lead the students through this series of exercises.

Spirit varnish pad polishing is unusually dependent on the “feel” feedback loop running through the brain, down the arm, into the hand holding the pad, the nature of the interaction of the varnish laden pad with the surface being polished, and the resultant information signal being sent back up the hand and arm to the brain. With practice this OODA loop becomes habituated like almost every other aspect of creativity, but at the beginning it is critical to decode the process. Dave is really excellent at that decoding tutorial.

This workpiece is purposely bland so that the visual information will be derived solely from the varnish being laid down. Dave charged his pad and began sweeping his pad across the surface in a landing-and-takeoff motion, developing both the motion and rhythm for the equation of pad + varnish charge + temp + humidity + character of the workpiece, feeding into the OODA loop instructing the process.

In short order the sheen began to build such that the evidence was clear of the proceedings. After a few minutes of the pad polishing there was enough build-up that Dave moved on to a more visually appealing workpiece.

The mahogany veneered panel was just the thing to emphasize the possibilities of this most simple finishing technique. Given the wax filled grain of the surface the build-up went very fast; the time codes on the images indicate a total work time two minutes between the previous picture and the following picture.

With this encouraging demo completed the students began working on their own workpeices. They took it it like a fish to water.

One of the issues we struggled with for the weekend was the cool, damp weather. As the spirit varnish was applied the solvent evaporation brought the surface temperature of the workpiece down to the dew point, and we wrestled with cloudy films. Once they began to become manifest it was time to set the workpiece aside and after an hour or so the film clarified.

It is worth reiterating the purposes of the Big Board exercise, which in many ways is the foundation for the whole workshop curriculum. When I present a 2-foot by 4-foot piece of unremarkable luan or birch plywood to the students and tell them they will be finishing this entire board with a 1-inch watercolor brush, their quizzical expressions are met with my exhortation to hang in there as the outcome will be workshop-life-changing. Once this exercise is completed, actually it is an entire series of exercises embedded into a single plywood board, the student will have become fearless Finishing Ninjas. Everything else in the workshop is frosting on the cake.

I have come to refer to each finish application session as an “inning”, and the big board exercise for the workshop entailed three innings. First thing on Day 1 it was a light abrading with a pumice block followed by four or five consecutive brushed applications of the shellac varnish, then set aside for several hours. Inning 1 was my opportunity to preach about the selection of the correct brush and proper use of that brush. Even by the end of Inning 1 it was readily apparent that a near-perfect film could be built with that 1-inch watercolor brush, with no resulting overlap margins due to good brush technique.

Inning 2 commenced with a light sandpaper smoothing of the material deposited during Inning 1, followed by another four or five consecutive applications of the brushed spirit varnish. Again, this was set aside, this time until the following morning.

By this point we were well on the way to constructing an excellent foundation for the final elements of the exercise as almost a dozen layers of spirit varnish were flowed on skillfully.

As with many woodworkers the students for the recent workshop were enamored with the mystique of shellac spirit varnish pad polishing, also known in the trade vernacular as “French polishing” although I am unpersuaded by the accuracy of that moniker (I have listened to impassioned recitations by French craftsmen referring to the practice as “English polishing” because true historic French Polishing is a wax spit-polish technique). To that end I asked my long time pal Knoxville Dave to stop by for the weekend and he was a great addition to the fellowship and learning experience.

Dave provided the hands-on instruction for the exercises of pad polishing through the weekend, beginning with constructing the pad itself.

As is my (and his) preference the starting point is a roll of surgical gauze, cut into long strips then folded and rolled into the ball that is the core of the polishing pad.

Once the ball is formed to fit into the palm of the user, it is wrapped with a piece of fine linen to serve as the disposable contact surface for delivering the dilute shellac varnish onto the surface of the workpiece. (I am always on the lookout for fine linen rags at antique shops, and with great success in recent years. If I have to use new linen I rely on an ultra fine weave known as either “handkerchief linen” or “Portrait linen,” the latter being used by fine art painters. Still, I prefer well-worn tablecloths or napkins and have a good stash.) At that point the entire tool is “conditioned” with the introduction of the spirit varnish to saturate both the ball core and the outer sheath, not enough to be dripping wet but enough to leave a trace of the spirit varnish when pressed into the opposite palm. At this point the pad is ready for work.

It went into a dedicated sealed jar awaiting the combat to come. Dave and I showed our own polisher jar containers, mine has served me with the same pad for almost two decades.

Now it was time to prep the panels to be polished out. By the time we finished I think there were five separate pad polishing exercises to be completed.

NOTE: Every aspect of this workshop is dealt with, sometimes with ridiculous detail, in my completed upcoming book A Period Finisher’s Manual; certainly much more detail than the blog. In fact, the workshop has re-lit the fires of getting that beast finished and off my neck.

The first of the class exercises, which in fact became the foundation of a half-dozen exercises, was to take a 24″ x 48″ panel of cheap (not inexpensive, this is 2021!) luan plywood panel and get started building the finish on it using a 1″ flat watercolor brush. Trust me, the proof of the pudding is in the tasting and in the end this leads to a tasty treat.

Even before we started applying the finish was the surface prep. That alone was a paradigm threat as the prep work was accomplished by rubbing the wood surface with the tool most prominent two centuries ago – a pumice block. Sandpaper was expensive and to residents of a time where surface prep is done with a power sander, the performance of a pumice block is truly surprising.

With the surface abraded and smoothed, and the detritus cleaned, it was time to mix up and apply some varnish. Since I have hundreds of pounds of lemon shellac flour, that is what we used. We each mixed a jar of approximately 3-pound shellac varnish with the shellac flour and 190-proof liquor. (Approximately a lean 1/4-jar, then filled to the brim with alky.)

Soon enough we were applying the first of dozen coats of spirit varnish on the panels. I gave impassioned instructions about how to apply brushed spirit varnish so that there are no overlapping marks, and I must say that the participants each accomplished that task perfectly.

The first coat was immediately followed by a second, and a third, and a fourth. Then it was set aside until the end of the day.

In keeping with my current “marketing” (non-) strategy for workshops, a while ago I was approached by a group of fellows commissioning a Historic Wood Finishing weekend workshop at The Barn. Once we set the schedule it turned out that there would be two slots open for anyone else who wanted to take the open places. If this interests you let me know. As always, the emphases will be on shellac and wax finishing for three days. The schedule for the workshop is October 9-11, 2021, and the tuition is $375.

With the two halves of the Kindle case ready, I glued on band of leather to bring the two of them together. The gluing was only to the faces of the case with the back edges unglued so that the case could be folded open with the two halves face-to-face.

Once the two halves were put together I took some scrap felt from my rag bin and glued that into the cavity holding the Kindle. That was a nice effect, except for where I slipped with the razor blade while trimming the felt and cut off some of the cypress veneer. I hate when that happens, and will repair it when I get a chance.

With everything together and complete I spent a little time padding on some more shellac. I will probably repeat this periodically to build it up a bit more, but I wanted the case to get to work. I stuck on some velcro dots at the two corners to hold it together when not in use and called it “finished.”

Today I wrapped up (mostly) three of the “rubbed through” boxes and have put two to work to hold some of my smaller Gragg sculpting tools.

This one is black-over-red.

This one is red-over-black.

I did both of these with pigmented shellac with lemon shellac as the film forming component. I added Bone Black and Vermillion Red powders to taste, then three or four clear coats over the top after composing the pattern with wet sanding. Since these will get jostled at least if not outright “beat up” I have no plans to bring them to a mirror surface. I might rub them out with some Liberon steel wool and Mel’s Wax once the surfaces get really hard in a few weeks.

It is nice to have most of my smallest brass spokeshaves in the same box. I bought four sets of the ones offered by many tool merchants 35(?) years ago and am delighted to have them on hand. With duplicate sets I have total freedom to modify them as needed. These tiny tools are amazingly productive but it takes strong finger tips and a good “feel” for using them. Fortunately Mrs. Barn lets me massage her feet for a couple hours most evenings so my hands are up to the challenge.

Recent Comments