En route to my recent presentation in Franklin TN I stopped to visit my long time friend DaveR in Knoxville. He arranged for us to visit renowned local marquetuer RobertL at Robert’s house about an hour away, and we spent an enchanting morning and lunch with him. Beginning with the nonpareil view from the deck of Robert’s house the entire visit was an unmitigated pleasure.

Dave have given me forewarning about Robert’s stash of old veneers, but still I was not fully prepared for the racks and piles of old, thick veneers. Robert indicated that his passion for marquetry and collecting veneers began back in the 1950s, and he’d had the opportunity to acquire several much older inventories of veneer from furniture makers and other craftsmen of generations previous.

As we toured the delightfully used warren of spaces in the basement, racks of veneers, portfolios of patterns, and the inventory of artworks completed and in-progress had my head spinning. Robert carefully explained and demonstrated his techniques, and it is impossible not to appreciate the result.

I have no doubt that we are living in a Golden Age of furniture-related craftsmanship. If you do not share my view, it might be because you are distracted by the nagging suspicion that civilizationally we are not living in a Golden Age, but rather we are living in, no, locked inside of, a fetid portable toilet of culture teetering precariously on the precipice of disaster, knowing that sooner or later, probably comparatively sooner, the cliff will give way and the septic tank we are locked inside will go over the edge and we will be doused with excremental effluvium as the box tumbles down, hurtling towards the chasm that is the coming Dark Age. (Hillary Clinton vs. Donald Trump? For the President of the United States? Seriously? Give me another blue pill.) Hmm, that might be a topic for a conversation at another time.

Back to this Golden Age of furniture craftsmanship. For most of my adult life I have been studying the historical furniture-making trades in on manner or another. While I was/am usually trying to gather more information to assist my decision-making in the restoration and preservation of historic furniture, I have learned enough that I have come to the conclusion that right now more fine furniture is being made than at any point in the past. The numbers of excellent furniture makers is huge and increasing, as reflected in the burgeoning growth of organizations like the Society of American Period Furniture Makers, vibrant networks of furniture making and woodworking guilds and clubs, thriving literatosphere including magazines, blog sites, and enterprises like Lost Art Press, complimented by a legion of passionate researchers and innovators rediscovering the special knowledge of the past and creating new knowledge all the time.

While I was at the Smithsonian a couple times a year I would get a call, usually from an interior decorator, about which line of antique replicas was the best for her current project. My reply was to exhort the inquisitor to do a little searching as the proximity to a fine custom furniture maker was certain, and that these makers would produce instant heirlooms rather than mere manufactured replicas.

The same quest for excellence, in both quality and quantity, has become abundantly manifest in the tool world. When I started in the trade more than forty years ago I knew of no source for new, high quality precision woodworking tools. Those that were available and known to me were inferior.

Now there are literally dozens of tool-makers providing superb tools. Some are larger scale broad spectrum providers while many are single craftsmen working to exacting standards. A brief, cursory search can find them. Others are concentrating on specific tool forms; for example there are probably a dozen hand-plane makers and at least a half-dozen saw makers. When I chat with them at woodworking events they all seem busy and booked, with horizons expanding before them.

As with other human ventures, some of these tool-makers are out at the edge, squeezing out every last iota of quality from their efforts. In this context I think of former saw maker Andrew Lunn and current plane maker Konrad Sauer, both friendly acquaintances of mine. Their work is so refined in quality that it is almost different in kind. I’ll offer two personal anecdotes to reflect on this.

Three years ago Jameel Abraham held the first French Oak Roubo Project (and don’t get me started on the renaissance of interest in historic work benches, of which I am fully guilty) and we were gathered for a barbecue at Ron Brese’s home, Ron himself being a plane maker of the very first rank. Ron had been assiduous in collecting tools of his fellow contemporary tool makers, and for the occasion he set out several magnificent dovetail saws on the bench and invited us to try them at our leisure. The first person stepped up to the bench and began cutting, and the rest if us just clustered and chattered in the shop. A few minutes later came the sound of a saw that was so magnificent that literally every head in the room snapped around to focus on the sawyer and the saw. Each of the saws in the sample set were great, but this one was of a completely higher level and you could tell just by the sound. It was Andrew’s. Sadly for me he has withdrawn from the world of saw making and the prices of his saws, when they do change hands which is not often, places them outside my realm. But all is not lost as there are a host of sawmakers pursuing this level of quality, and the gap is getting smaller all the time.

The second story is from this past spring’s Lee-Nielsen tool event in Covington, Kentucky, concurrent with the grand opening of the Lost Art Press World Headquarters. I’ve blogged about this event before. Konrad was set up with a few of his planes, including a new one (new to me at least). I don’t play with tools much at these events as I know 1) they are all magnificent, 2) I don’t really need them, and 3) even if I did want one I might not be able to justify their expense. Any, my friend and fellow Studleyista Sean Thomas asked me, “Did you try that new plane Konrad brought?” It was in the general form of a jack plane. I had not, and at Sean’s encouragement I picked it up and took a few strokes. Sean can confirm that I literally gasped at the performance and feel of the tool. It was that good.

I am not trying to kiss up to Konrad but merely indicating the place of the toolmaking craft at the moment. Yes his tools are setting the standard, but there are a posse of plane makers hot on his heels.

Who benefits from this? We do! We may never be able to afford one of Andrew’s saws or Konrad’s planes, but we will be able to consume the products cascading down from a whole cohort of makers producing tools that were simply not available before, each of them inspired by and in competition with these standard-setters.

In an upcoming blog “My Dovetail Saw Gets A Baby Brother” I will recount how this cascade washed over me recently to a wondrous effect.

In addition to next month’s workshop on traditional woodfinishing (June 20-22) I will be hosting a week-long workbench building class at The Barn July 25-29. The event was to have taken place in late September, but since I was still not up-to-speed by then I needed to postpone.

The goal is for each participant to go home on Friday afternoon with a finished workbench that will serve their needs and those of their descendents for centuries to come. It may not be all tricked out the way everyone wants, that will be up to each person to do ex poste, but I am absolutely committed to creating a process by which every bench goes home finished on Friday night. If you are interested in participating in this adventure, drop me a note here.

Each participant will select which bench they want to build, an English/Nicholson workbench or a French/Roubo bench. In order for them to make a well-reasoned choice, and for me to work out any bugs in the system, I made one of each bench. Either in advance or on Monday morning we can together choose which bench each participant will build as that will determine our stock preps.

The benches will all be made from mostly-clear 2×12 southern yellow pine that I purchase over in the valley, and each requires almost exactly the same quantity of materials. I will obtain all the materials for the benches, no deviations or substitutions will be allowed. Not because I am being a stinker or am making bucks off the materials (I am not) but because the only way to get this done is to standardize as much of the process and materials as possible. And, the construction methods will be machine and power tool intensive, with very little finicky hand work required.

I built the Nicholson bench first, and the next several blogs on this topic will unfold the manner we will be working in July. My initial task was to establish the dimensions, in this case 96″ long x 24″ deep x 36″ high. Based on that I started cutting up the lumber.

The legs were made such that each leg is two lamina of the 2x stock half the width of the original 2×12. The only measuring was on the longer piece, which I made 36″; the shorter piece was simply cut according the the width of the 2×12 against the end of the 36″ piece.

Assembly employed one of my favorite rough stock methods, namely deck screws with washers as the clamp holding the two pieces together while the glue sets. In this case I used white PVA adhesive.

Once the glue was set, the screws were removed and the edges planed flat and square. With that, the legs were done.

I finished mixing up a variety of paste waxes to demonstrate at the upcoming Professional Refinishers Group meeting. Since canning jars come in flats of a dozen, I made a dozen varieties, actually nine varieties but added coloration to three of those. They range from easy to use soft beeswax to harder to use but much higher performance blends of beeswax, shellac wax and carnauba wax with a trace mount of acrylic resin additive. The latter is a very impressive formulation that I might start producing if I can be convinced of its efficacy through testing by craftsmen at the bench. Producing wax and resin finishing products has always been part of my plan. Since The Anarchist’s Daughter has spurred a renewed interest in small scale paste wax production, this might be the time.

I also prepped about 45 shellacked panels to use as substrates for waxing and polishing so that we can evaluate the blends on an even playing field. Who knows, while at Group we may come up with something new.

I found this exercise to be so much fun that I will include it in the upcoming Traditional Finishing Workshop at the Barn June 20-22 if there is any interest by the participants. If you are interested in coming, drop me a note here.

DOVETAIL-SLIDE PIANO MAKER’S “STUDLEY-ESQUE” VISE

================================================

Note: I’m reposting this from Brian Rytel’s blog http://zengrain.com/piano-makers-studley-esque-vise/ — DCW

================================================

Reflecting, I realize that I’ve found a lot of amazing tools in Northern California. I’ve hauled enough iron ~400 miles south to the LA area that compass readings might be affected. Luckily my latest trip up was no different.

As they often are, my trip was a bit last minute. I stealthily slipped up and visited the Alameda flea. It yielded a few gems but not enough to even take the iconic tailgate shot. The short version is that I now have a Stanley No. 10, something I’ve been hoping to find for awhile. The big arn from Alameda was a rare model sewing machine, so ’nuff ’bout that.

My long-awaited No. 10

Later, I was hunting through antique shops in the Sierra foothills. I was hitting closing time but was still empty-handed. One planer gauge tempted me but was overpriced. I walked into the last open shop. This one was new since my last visit. Initially I had low hopes with all the dreck (to me) but curiosity paid off with a cabinet of Plomb, Proto and Snap-on to look through. Perhaps I was a hard sell (or cheap?) but nothing tickled my fancy in the wrench department. I wandered further and saw a coal forge & blower on wheels and on the other side of the display: a vise.

What I definitely don’t need is another vise. Right?

Well, I needed this vise. 13″ wide jaw, at least 14″ of clamping depth, a screw that spins freely enough to make you too speechless to utter “quick release”, and a handwheel.

I asked the gent at the front about a price on it. He got up and said “have a couple back there, have to see which one”. After a few steps on he remarked “Oh, you mean that one. It almost killed me getting it off the bench”. Apparently, he was just as surprised by it’s heft as I was, except I wasn’t beneath it when I made the discovery. We worked out a deal and he even loaded it for me (to my great relief).

The general pattern is often called a piano maker’s vise. With all of the hullabaloo about Studley lately, these are often referred to as “Studley-esque”. Don Williams did a substantive amount of research into the Studley vises as well as all other elements of the toolbox for his book. In the rounds ofpublicity preparation for the book he posted several updates about piano maker’s vises that he sourced and eventually included in the exhibit. I think he located a dozen or so, and several are the same design of mine. He notes on the “Ben” vise that it’s numbered 15 on both castings, which leads him to the conjecture that there must be fourteen others of that pattern. Well, I am happy to report that we can boost that count to eighteen total. My vise is marked with 18 in the same location.

Initially, I was temped to refer to this design with the last name of one of the other owners. Given the quantity available, I think they should just be called the dovetail-slide pattern.

Here is documentation of the family:

and of course mine:

- Brian Rytel (#18): http://zengrain.com/?p=1240

- photo gallery:

That accounts for four of at least eighteen. Not bad for tracking down trivial industrial artifacts over a century old. If anyone can find additional examples, photos, documentation or serial numbers for this pattern of vise, please let me know.

photo courtesy of Narayan Nayar

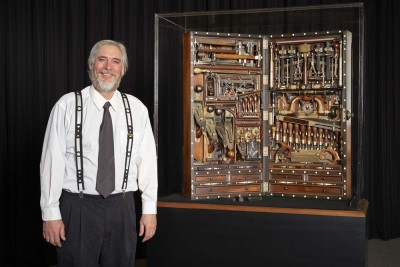

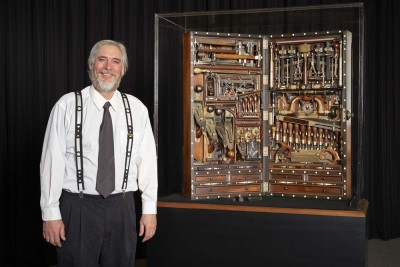

To tell you the truth I don’t really care what you were doing this time last year. I only wanted to spark my own reminiscences of being in the midst of three weeks of 14-hours days as I was fulfilling the dream going back almost thirty years — creating the definitive exhibit and book addressing the Tool Cabinet and Workbench of Henry O. Studley, piano maker of Quincy, Mass.

The exhibit was the culmination of several years of diligent work, and looking back on it I can honestly say that there was nothing about the physical manifestation of the experience that I would change. Not a single thing. It looked exactly as I envisioned it from the beginning.

I got to greet and chat with more than a thousand fellow Studley enthusiasts, even if I did not recall precisely all of our conversations.

Some time after the exhibit I was corresponding with one of the Handworks exhibitors about the special reception I held for them the evening before the exhibit opened. In our exchange I apologized for not greeting him at that event. He replied that we actually talked for quite a while. Oh well.

I guess that is one thing I might change if I could. Make time slow down so I could savor the moment even more than I did. By the end I was, in the words on my pal MikeM, “Pond scum.”

I didn’t “close the books” on the project until we did our taxes last winter. When Mrs. Barn learned the numbers, she just grimaced and said, “Well, you were going to do it anyway, weren’t you?”

“Yes, I was,” I replied. “I couldn’t not do it.” Not for anything short of personal tragedy.

There is another set of books for The Studley Exhibit and the accompanying Virtuoso that will never close as long as I have breath. That set of books is the one from my heart, as I reflect with quiet joy on the contacts and friendships that flourished in the maelstrom.

Of working with Chris and John at Lost Art Press, whose support never wavered.

Of my collaborator Narayan Nayar, whom I am honored to count as a treasured friend. (I remember Chris’ comment when I told him I wanted to approach Narayan to execute the primary photography for the book. “There’s nobody better,” he said, “but you will probably want to kill him before it is all done!” I didn’t.)

Of getting to befriend Studley Collection owner Mister Stewart, a delightful, brilliant, and humble fellow who is among the most creative and successful men I have ever met, yet still comes to work almost every day in blue jeans and a t-shirt and still plays hockey as he approaches his eighth decade. We remain in contact to this day, as we’ll call or write each other about a variety of subjects. He recently called me to ask something about shellac. How cool is that?

Of our gracious and accommodating host Mr. Heath, steward of the Cedar Rapids Scottish Rite Temple, whose company and excitement for the project was a constant source of encouragement.

Of friends like WilliamD who valiantly defended my vision for the exhibit in the woodworking blogosphere against the angry postings railing against what I was trying to do with the exhibit experience, often stating with absolute certainty that I was simply a profiteer gouging the audience. I did not know about these on-line exchanges until after the fact, I was to busy being productive, but thank you William for standing up to the ignoranti of the woodworking forums. It did confirm my reticence about participating in them. I simply do not have enough IQ to risk losing any of it. (It’s sorta like eating breakfast in the motel lobby where the Today Show or Good Morning America or Oprah or Maury or some other abomination is on the television — I can feel myself getting more stupid and ignorant by the minute.)

The docent group picture just before the opening reception. Photo courtesy of Narayan Nayar.

Of friends old and new, one friendship of more than thirty years, a couple newly minted and the rest in between, who came as volunteer docents and hands for the installation, interpretation, and deinstallation of the exhibit.

Think about that, almost a dozen people came on their own time at their own expense simply to support me personally and be part of a memorable and historic event. Now that is a treasure you hide in your heart.

Perhaps my oldest friend Rick Parker, who drove eight hours each way in order to spend eight hours working with us.

Rick Bean, Jan Bohn, Randy Bohn, John Hurn, Mike Mavodones, Mike Mascelli, Derek Olsen, Rick Parker, Sharon Que, Bill Robillard, Sean Thomas. These are the names to remember, and I do. I correspond or speak to each of them regularly even now.

Of cherishing the presence of my wife and daughters at experiencing the pinnacle of a career.

It does not get much better than that!

That’s what I was doing this time last year, having the time of my life. I just wish I could recall the details a bit better… Some year it will be time to let those memories recede into the vapors.

But not this year. After all, it was unforgettable!

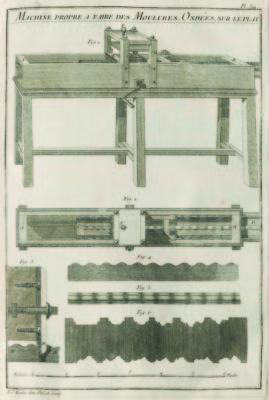

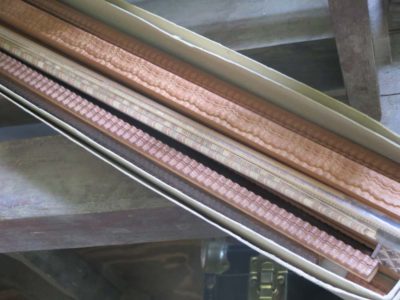

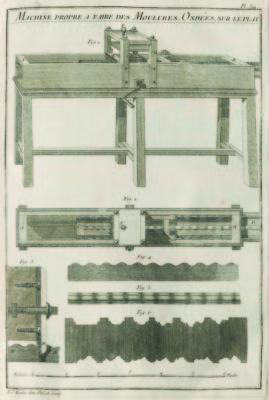

Given my recent acquisition of four dozen prints barbarically cut out of a First Edition of Roubo’s L’Art du Menuisier (c. 1771), among which were the fanciful machines on making ripple moldings, I was immediately overcome with the idea that I had to make some frames for these prints. And of course those frames must feature prominently some ripple moldings.

My memory was drawn back to some correspondence with RichardB, an architectural conservator whom I have known for more than three decades. Much like me, Richard is a collector of knowledge, the older and more esoteric the better. Anyhow, Richard knew a nearby fellow Jerry who had a ripple molding cutter his father (or grandfather?) had built.

I arranged to meet with Richard and have him take us to visit Jerry’s shop, which turned out to be a remarkable and inspiring day.

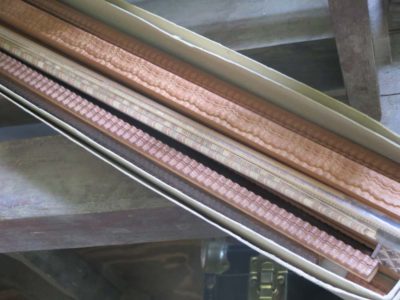

Yes indeed, Jerry had a motorized ripple molding cutter that performed astonishing feats, producing unspeakably elegant molding stock.

I am pretty sure the master pattern rails on which the cutter head rides are made from Delrin or HDPE, I somehow forgot to ask, and the cutters are all hand made from various tool steel stock.

I stood and watched it for a long time, it is hypnotic watching the cutter head moving back and forth, scraping out the profile and the ripple pattern.

Jerry’s passion is replicating historic clock forms and he uses all manner of ripple molding on them. I think Jerry is too busy to make any moldings for me, but seeing his in person sure lit a fire under me to make one.

Maybe next winter, or the one after that.

That’ll be worth a blog entry or ten.

I’m doing some prep for an upcoming presentation/demo for the Professional Refinisher’s Group on the topic of blending and producing your own custom paste waxes. The topic emerged at last year’s meeting when my friend MartinO talked about the properties and performance of commercial paste waxes from his considerable studio inventory. It was clear from the question session that there was a lot of interest in having tailor-made products at your finger tips, hence this presentation.

So I’ve been making like a mad scientist in the shop, creating everything from the elegant and ancient formulation being now produced by The Anarchist’s Daughter to some fairly exotic blends that emerged from our work at the Smithsonian.

The processes are pretty straightforward and at the personal shop scale about all you need is a hot plate (my favorite one is one from a fondue crock as I don’t have to think about it — if it is hot enough to melt but not burn cheese it is perfect for making paste waxes), a sauce pan, digital scale, and the supplies themselves. For this process I use beeswax, carnauba wax, shellac wax, and high-temp micro-crystalline wax, along with turpentine, naphtha, and some additives like pigments, rottenstone, and acrylic resins which I use in trace amounts for some of the formulations.

It’s both a delightful and melancholy time as it forces me to remember my years of friendship and collaboration at the Smithsonian with the late Mel Wachowiak, with whom many of these discoveries were made in the lab.

I’ll make sure to post the recipe handouts and any event notes when I’m all done.

A couple weekends ago I spent a delightful time with the Cumberland Furniture Guild in the Franklin, Tennessee shop of our host Len Reinhardt. On Saturday afternoon I gave two lectures, one on The H.O. Studley Tool Cabinet and Workbench, and the other introducing the topic of pre-industrial finishing materials and techniques.

The real fun began on Sunday morning as we conducted a hands-on workshop on the topic with lots of, well, hands on work on raw mahogany plywood panels. I provided the brushes and shellac, with information (hectoring) about the quality of materials and tools.

Each participant was able to execute a completed panel of brushed-and-burnished lemon shellac, and one with a molten wax finish applied over a polissoir-burnished surface. Even these two very basic finishes are pushing the time envelope for what can be accomplished in a one-day workshop. Normally I make this a three-day event but we did what we could in that one day.

Brushing began in earnest as I was trying to stay one step head of them.

Once the brushing was done we moved on to molten beeswax finishes.

The first step is to get the beeswax deposited onto the surface,

Then to distribute it evenly throughout. Once that is done the panel is set aside for the wax to cool and harden.

I was delighted to welcome my friend Dave Reeves from Knoxville to provide instruction on using asphalt as a toning material (it is one of the basic historical methods for darkening the surface) and padding on shellac spirit varnish.

There was intense interest in watching him do this simple but elegant finish. I used to do a lot of padded finishes, but in recent years my projects have taken me more into the burnished brushed finish world.

But there is no doubt that a well padded surface is eye popping.

We then returned to burnishing the brushed shellac finish with 0000 Liberon steel wool and paste wax, continuing until they just got tired of rubbing.

With the molten beeswax cooled all that was left was to gently scrape it smooth then polish it out with a soft cloth.

Like I said this is a topic I normally cover in three days to explore it more fully, and it happens I will be doing just that June 20-22 here at The Barn. Normally I give shorter workshops over the weekend but am trying this Monday-Wednesday schedule by request, so we will see how that goes. If you are interested in joining in, drop me a note here.

Recent Comments