Very often in the midst of a lengthy undertaking I need a brief diversion to recharge my batteries. Given my current work on building Gragg chairs and recording the process for video and the seemingly endless work on A Period Finishers Manual I’ve been finding myself sitting at the finishing bench for an hour here or there to continue my exploration of the Asian lacquerwork aesthetic by other means. The particular projects are inspired by the Accidental Woodworker’s frequent exercises building small boxes for his tools, combined with my need to keep better track of the multiple small spokeshaves and spoon-shaves I use when sculpting a Gragg chair’s edges and shape. I’ve also got my sandpaper box that has been primed for years and awaiting its final decorative surface.

I am particular taken by the lacquerwork aesthetic of the negoru finish, or “rubbed through” surfaces, almost always executed in red and black. Rather than building boxes from scratch I used some of the paulownia or pine boxes from Michael’s that I have acquired over the years as teaching projects for japanning classes. In this case I was working black-over-red, but also had some red-over-black boxes that were never finished.

For the sandpaper box I used oil paint, for the others I used shellac. I have yet to complete a box with polyester but will soon. Some day I’ll post a blog series on these decorative options.

In one sense the learning velocity for Day 3 is the same as Day 1 and Day 2, but the psychological impact of everything coming together in a beautiful outcome is almost incalculable. One thing I am mindful of is that most Day 3s of workshops are structured to make sure any meaningful instruction occurs by mid-day, as the typical impetus is for folks to start heading back home sometime in the afternoon. Sometimes students will stay until evening, but in this case all three had lengthy drives home (two to central NC and one to CT) and headed out mid-afternoon to get home before dark.

If I had to summarize the events of the third day it would be encapsulated in the word “rubbing.” The central focus of that action was the very large panels that had been varnished with brushed shellac the previous days. These panels were divided into four sections to be finished off with different rubbing protocols, including making and using abrasive pads for pumice and Tripoli/rottenstone, both with and without paste wax. Another section was burnished/abraded with Liberon 0000 steel wool and paste wax.

Though I knew the results in advance the students did not, and their excitement at seeing the results of their own hand work was most gratifying.

One student even brought a sample panel from his previous finish work and compared it to the panels we completed during the workshop. Needless to say the smile could not be wiped from his face. I didn’t quite get the camera angle perfect but you get the point between the almist gritty, brassy smaller panel and his new lustrous, almost glowing surface.

Our final chapter of the workshop was shellac spirit varnish pad polishing, a/k/a “French polishing.” As with the other pad-based processes, rubbing out with tripoli or pumice, they each made their own spirit varnishing pad. All these pads were made with vintage linen outer cloths and new cotton wadding inner cores, and all these were theirs to take home in a small sealed glass jar. These pads should serve them well for many years to come.

Spirit varnish pad polishing is very definitely a technique requiring an informed “feel” about how it is supposed to progress. Even though this was an introductory effort for all three students, they really took to it with enthusiasm and excellent outcomes being the result. It was delightful to see the smiles and satisfaction of accomplishment.

Though I failed to get a final photo of us all, along with their sample boards going home with them, I believe it was a woodworking-life-changing experience for them. As I told them at the outset, my primary goal was to give them confidence at the finishing bench and dispel any intimidation they might have in that regard. If their notes to me afterward were any indication, it was a success.

I want to thank for your “Historic Finishing Course” at the Barn last week. It was over the top in how it exceeded my expectations; by the end of the workshop I was seeing the process you taught working to a superb result under my own hand. A really cool result–and well worth three days of my time to learn it.

And,

I want to thank you for an awesome class! The fellowship was really great and I came away much more confident applying a lovely shellac finish.

[Yup, my compewder power cord arrived from South Carolina and I am back in bidnez. — DCW]

Day 2 included the continuation of previous exercises begun on Day 1 and the addition of some new ones to fill out the syllabus.

With the large panels having already been built with two innings of brushed finishing the preparation for the final application of brushed shellac was underway with the surface being scraped. I find scraping to be a “lost art” among contemporary finishers for the most part, although it was a very common weapon in the quiver of an 18th century craftsman. For convenience sake I/we used disposable single edged razors from the hardware store that I buy by the hundreds.

For the final application of the shellac varnish I had them switch from a 21st century nylon/sable blend watercolor brush to an oval bristle brush, much closer in style to that of 250 years ago. This gives the students a variety of experiences for similar tasks.

I presented a very brief demonstration of using a pumice block to prepare the raw wood, which yielded a surface that was surprisingly (to them) smooth.

Then on to the molten wax portion of the program, wherein they prepared two sample boards for different purposes. The first was to create a “wax only” finish which I think is the most difficult finish to do well, and secondly to fill the grain for a panel to be pad polished tomorrow on Day3.

While the wax was cooling the students moved on to a pair of exercises designed to give them facility at complex surfaces. The first was to varnish a carved and turned spindle and the second a frame-and-panel door.

While they were doing that I was playing some more with molten wax finishes. Like I said, it is difficult to get perfect.

Late in the afternoon we saw this “meal on wheels” right outside the shop. Clearly they are terrified of human proximity.

Thus endeth Day 2.

Last week was my almost-annual workshop in Historic Finishing, three days spent introducing the notions of systematic work with shellac and beeswax. This year I had three students which allowed for a lot of great fellowship and one-on-one instruction and problem solving.

It began with a discussion of the strategy of finishing I developed many years past, emphasizing the Six Simple Rules for Perfect Finishing. As always my goal is to not only teach and inform, but to change attitudes. Usually woodworkers are indifferent at best and terrified at worst to finishing, and again this year I saw the students leave with a whole new level of confidence. I cannot say they departed with my own mindset of looking forward to any finishing task, but at least they were no longer fearful of it.

After the opening lecture they got to working on the first of a dozen exercises I had devised for them. This one was brushing shellac on a large panel, building up about a dozen coats in three application sessions, or “innings.” Using only a one-inch brush this exercise develops excellent hand skills at applying a finish evenly over a very large area, and lays the foundation for some Day 3 exercises.

We then moved on to the means of preparing surfaces in general (the initial large panel exercise has to fall a bit out of order since it required three sessions to complete the applications; the start of Day 1, the end of Day 1, and the start of Day 2). Thus much of the day was spent building up Popeye-like forearms, a/k/a using a polissoir.

I also demonstrated the use of a pumice block for smoothing wood. This was a very common procedure in ancient days, an analog to our own use of sandpaper.

Preparing panels with the polissoirs and then a polissoirs-plus-cold-beeswax occupied much of that afternoon, followed by a light sanding of the large panel and re-application of the 2-pound shellac from the morning.

And thus endeth Day 1.

Being a long time shellacophile in the Age of Ebay I browse that site’s holdings periodically for shellac-related items of interest. As a result I own a Zinsser money clip, several generations of sales and technical brochures, a book or two, and several old timey shellac bottles and cans. Recently my visits to ebay for this purpose have dropped off considerably, coming now only to once every month or two instead of a couple times a week. I’m just too busy to spend that time, and frankly have not found anything worth buying in a few years.

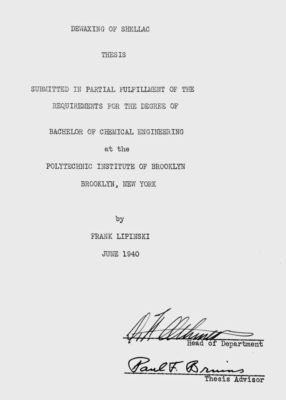

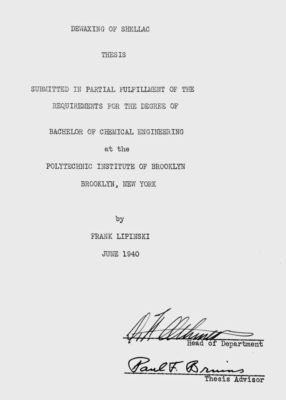

That all changed a couple weeks ago my pal TimP sent me a note indicating the availability of these three treasure troves, bound compilations of research monographs and related materials from the three gravitational centers of the Shellaciverse: The Indian Lac Research Institute; The London Shellac Research Bureau; and the Shellac Research Bureau, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

There was a “Buy it now” option so of course, I bought it now. It was my moral duty. Earlier this week the hefty package arrived here in the wilderness and I eagerly opened it to see if it was solid gold or simply dross. Each volume is several hundred pages of documents comprising dozens of monographs, technical notes, and other publications. A quick glance indicates that almost half of this is new to me so it constitutes a substantial amazing addition to the archive.

Thanks TimP!

It will take some time, perhaps even needing to wait until the winter reading season, but I will get through the books and digitize them for inclusion into my electronic version of the archive.

Note to self: resume posting publications to The Shellac Archive!

PS With the arrival of Spring like a freight train, some recent eye surgery (my 21st), a little travel, and a heavy video production schedule I simply haven’t had much time nor energy to blog lately.

Many years ago I contacted the archivist of the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institution to glean their holdings of a renowned body of research conducted there before and during WW II under the auspices of the famed coatings chemist William Howlett Gardner. In the precedent to that war much of the shellac research internationally was moved to Brooklyn to continue in safety. (Imagine a time when shellac was considered such a vital strategic material that research into it needed to be protected!)

The archivist, a gracious and knowledgeable woman nearing the end of her long and distinguished career of shepherding the scholarship records of the university, told me a fascinating and heartbreaking story.

At some point in the not-too-distant past a new university official of some sort had determined that the study of natural materials was a waste of time and that 100% of the future research would be about synthetic materials. As a result, there would be no need to keep records from past research into naturally derived materials by the chemists and chemical engineers. So, he ordered the library and archives to purge their holdings of all the records pertaining to some of the most insightful historic shellac research.

Thus my phone conversations with the archivist were bittersweet as it turned out I possessed more of their original research than they did. At her request I sent her a box of photocopies of the university’s own research. And with that, our interactions were completed.

Or so I thought.

A year or so later I got a phone call from the excited archivist with a great discovery. In reconstructing the events of the past, she had this tale to tell.

When the order was given to purge the library/archives holdings of the shellac research, the task was probably given to some of the university’s students working during the summer or some such arrangement. Apparently, at least one of that cohort figured that hand-carrying all that material up the basement stairs and navigating the warren of the archives was too much bother, so he/she simply moved them from one place in the basement to another place where it would not be noticed. Completely by caprice while searching for something unrelated, the archivist stumbled across a small pile of the original research from three generations ago.

Immediately I scheduled a trip to Gotham to peruse the findings, after first arranging for a friend’s sister (coincidentally also an archivist) to escort me through the terrifying (to me) jungle of humanity and subways that is New York City.

Sure enough, the archivist presented me with a small stack of original theses and research reports by the students of the sainted Professor Gardner. Part of the exercise was disorienting in a way as I could hardly imagine an institution of higher learning actually having dozens of students engaged in original or confirmational research on shellac. The archivist arranged for me to browse and photograph all the documents she had, and I have re-discovered these digital images in my own compewder as a result of migrating them from the old laptop to the new one.

Once I get these files edited and formatted they will become part of the Shellac Archive, whose presence should begin growing again now that I have the older, actually working template for WordPress on this laptop.

Stay tuned.

Those were the words of the manager of our locally owned bank as she held her finger poised over the compewder keyboard. “Once it goes, you can’t call it back.” I nodded, and she did it.

Turn the clock back several months prior as I was searching for a direct source for shellac wax in bulk. It was a Goldilocks sorta thing, most of the bulk suppliers in India wanted to sell hundreds of metric tons, and already-processed and packaged quantities here in The States were simply too expensive. One quote I got for an intermediate amount of 50 pounds was $3000 plus shipping! Earnestly I continued my search, even attempting to work through Alibaba. Finally I received a response from a small-ish (by industry yardsticks) supplier whose web site included a “Contact Us” function. What was intriguing about this response as opposed to the many others I received from similar information requests was that this came from a real person, not a bot. In every other case, I got a bot response.

As a result of that initial correspondence I requested a sample of their product, which they promised to send. Fully expecting disappointment, much to my delight a week later a sample with an analytical report arrived here in the hinterlands. It was splendid.

I melted it, cooled it, formulated some blends and products with it. It was perfect.

Further rounds of correspondence led me to the point of visiting my bank. We had negotiated the price for several hundred pounds of shellac wax, but the supplier was not plugged in to the world of credit cards nor Paypal. They dealt only in bank-to-bank direct transfers. My bank manager did some research and found out that such a transfer required going through two intermediate banks between my bank and the supplier’s bank. Since our bank was a locally owned enterprise it needed an American bank with international transaction capability, and the terminal bank at the other end was similar. Their bank needed a domestic (to them) bank to import the money and send it to them. It turned out that their funds transfer portal was a British bank based in Mumbai.

Finally those details were all ironed out and the paperwork was prepared and signed. That’s when the bank manager asked me what she did. “Are you sure?” she asked. “You can’t get it back if something goes wrong at the other end.” Given that the funds transfer involved several thousand of dollars flowing out of my account she was correct in making sure.

I took a deep breath and reflected on the risk. With the experience of the supplier complying with everything I had asked and everything they promised, I nodded my assent. She pressed the key.

Ten days later the UPS truck arrived with 500 pounds of shellac wax. I was not even home at the time, so the driver unloaded the cases into the barn himself.

In a series of interactions that eventually rested on risk and trust and eventually having to put my faith in the person at the other end of the interwebz that they would keep their word, the reward was heartening.

Thus the Age of Shellac Wax at the barn was born.

Periodically my contact in India drops me a note just asking, and one of these days I’ll respond with, “Yes, please send me another five hundred pounds.”

So now you know the rest of the story.

Recently I have been spending some time trying to impose order and completion to the Barn library, which might be a fancy way of saying I have been throwing away boxes full of paperwork from my career at the Smithsonian. My departure was six years ago, and at this point I am pretty certain I no longer need any organizational files from that era. As a result I have about a dozen cubic feet of fire-starting material.

An unexpected(?) result of all this commotion has been that I’ve (re)discovered a number of things I have written over the years. Not Schwarzian by any measure, but a fair pile nonetheless. Articles in magazines, chapters of books, handouts for presentations, and monographs for newsletters, etc. While the Writings page of donsbarn.com already has a goodly number of these missives, there are even more that have not arrived there yet. So I have set up my ancient laptop and scanner to capture these electronically and make them ready to post both on the blog and in the “Writings” section.

I should have the first one ready to go in a couple days, and hope to post a new one each week.

Oh, and I am working on readying some more material for the Shellac Archive as well. I still have a full “banker’s box” of material to scan. All tolled I have about 8,000 pages of shellac stuff.

The final day of my finishing workshop is all about the final appearance, including rubbing out and adjusting color the shellacked big panel, which had more than a dozen coats and looked like this at the start of the day.

Beginning with the 24×48 panel subdivided into quadrants, each received a different treatment. One quadrant was left untouched as a reference point, then work began on the second one. It was rubbed with Liberon 0000 steel wool, then rubbed with more Liberon 0000 infused with paste wax. The result is wondrous, and this is one of my very favorite finishes. It glows visually and is irresistible for just rubbing your fingers over its surface.

The third quadrant was polished with tripoli/rottenstone and mineral spirits, using a fine linen polishing pad nearly identical to that used for spirit varnish pad polishing. Any residue was wiped off and the surface received a light coat of paste wax. The resulting surface is absolutely spectacular.

The fourth section was rubbed with dry Liberon 0000 to give it a tiny bit of tooth for the addition of colorant glazing. Two gazes were tried, the first being asphaltum thinned with naphtha and the second being waterborne shellac with goauche colorant. They work very differently but both students had excellent results of a gentle color shift. The final step was to seal the glazing with a brush coat which both saturates the color and provides an even gloss.

The final project completed was rubbing out and waxing the raised panel doors and the table legs.

We took pictures of their gallery of work, and they headed for home. Both had very long drives, one to Louisville and the other to Syracuse.

The primary work of Day 2 was building up the finishes in preparation for the rubbing-out and toning of the final day.

The first task was to scrape the large shellacked panels with disposable razor blades to get them smooth as silk for the final application session to follow. True enough, disposable razor blades are not historically precise but scraping is, and using the disposable blades is the best way I can get the process integrated into the workshop. If done carefully the resulting surface is pretty much a flawless ground for the final layers of varnish.

We then moved on to some tables legs to get a little time in on working with “in the round” components. These are often a challenge for inexperienced and old-time finishers alike, but one key to success in this regard is a light touch and the right brush. I’ve found that a rounded-tip brush, sometimes called a “Filbert mop” with good bristle drape results in a near-perfect application every time.

The fellows worked so fast we had time to insert a couple of exercises, one being the use of molten wax on tables legs. We let a hair dryer substitute for a red-hot poker, but the results were acceptable.

Raised panel doors are also a sometime headache, but once you get the hang of the routine it works out pretty well.

Finally it was time to start on the spirit varnish pad polishing, a/k/a “French” polishing. Each of the students constructed their own pad from cotton wadding, then charged it with the spirit varnish. (This led to a fairly involved discussion about the fabrics that are best suited for which tasks in the finishing room. I asked my long time friend and Roubo colleague Michele Pagan, a textilian for as long as I have been a woodfinisher, to write a blog post on the topic. I will post it probably next week.)

By tapping it on their palm they knew when it was ready to go. And, it gives a lovely sheen to the palm.

The boards they had prepared on Day 1 were partially wax-filled and partially raw-but-burnished wood. Since so much of spirit varnish polishing is “feel” there was not much to do but turn them loose.

Before long there was a-glist’nin’ all over the place.

Another exercise that frankly I have never been able to get perfect was to fill the grain with beeswax and powdered colorant, pressed in to the wood grain with a polissoir. I need to work on this concept a little more, although Roubo promises success.

And with that we were done with Day 2.

Recent Comments