When building a Roubo Plate 11 workbench nothing is more important than getting the complex joinery of the leg top protruding through the slab bench top. I’m not 100% certain, but it might be the only important thing. As such, the layout and execution of the double tenon and mortise joint consumes more time and energy than all the other parts of the bench fabrication combined.

Jeff and Walter consult on the layout and execution of the joints in Walter’s bench.

I’m demonstrating on Joe’s bench one way to finish off the inside corners of the dovetailed mortise.

Not too surprisingly the hours of initiating this process brought about the most intense interactions between the “enthusiasts” and the students. At the beginning, Chris briefed the assembled throng on the assembly of the legs and stretchers, then inverted onto the underside of the bench top slab to provide for precise layout of the joinery for which there is no room for error.

Once again Francis charged in with only hand tools.

Steve’s concentration was entirely typical for the work of the week.

The following hours featured innumerable moments illustrating the intense concentration of the makers imposing the joinery on the slabs.

Karl is using the superb jig and tool combo brought by Devon. I think pretty much everyone in attendance made note of the combination and will try to replicate it.

I cannot recall who fabricated this particular drilling guide that Steve is setting up, but it certainly got a solid workout on our end of the room.

Joe took the effort to the max, working from on top of the bench top slab.

Once the dovetail mortises were done the energies turned to the inner rectangular mortises, where accurate drilling for waste removal was paramount.

Once the holes were drilled and the waste removed, the most serious hand-work of the week was underway.

Being the most experienced maker in the crowd, it came as no surprise that Chris got done first.

The second day began with a room full of roughed glued-up bench tops and the energies first turned toward the preparation of the legs.

Jeff and Ted making little timbers out of bigger timbers.

Leg stock was roughed from the timbers on hand, having been cut from remaining inventory that had been used for the tops.

68 legs needed to be readied, so once again the assembly-line teamwork jumped to the fore.

Jeff then manned the monster sliding table saw to establish the ends of the legs, which were pretty much custom fit for each participant’s preference.

Once the legs were cut the mortises for the stretchers were punched into the legs using Chris’ favorite machine at Wyatt Childs, Inc. This pneumatic power mortiser made quick work of the rectangular holes.

As soon as that was concluded the focus returned to the bench tops themselves.

The gobs of excess epoxy needed to be scraped off, and then the glued up slabs went through the planer one last time to clean them up.

Many of the slabs needed for the edges to be trued up so the leg joinery could be laid out precisely, and several hearty souls formed another Jointing Conga Line dance company.

As we had come to expected, Francis took a different approach. After scraping off the excess epoxy, he once again broke out the #8 and got to work.

The results were impressive.

Once the tops were flat and the edges trued it was time for the lengths to be cut. I had never experienced Festool World before, but it seems as though the tool line was the favorite of the gathered crowd. Joe was one of the fellows who brought their Festool Collection and set to work. I was impressed by the performance of the tool setup, but doubt I will be taking the plunge as I get by with my 7″ and 10″ Milwaukee circular saws and some aluminum angle bars just fine.

Joe cut his top precisely from both faces, but still a sliver remained for his handwork.

A somewhat simpler and scarier option was to use “Barbie,” the monster 16″ Makita timber saw that could almost effortlessly crosscut the slabs in a single stroke.

The end result for the day was the upside-down top with the legs sitting in place.

Joinery started the next day. Cutting and fitting the leg joinery into the top is by far the most difficult and fussy part of the whole project.

The first day of FORP 2015 unfolded pretty much the way the first day of FORP 2013 did, as we continued the “get acquainted” niceties — including ogling each others’ tool chests and their contents — and got down to the bidnez of hossing around tons of vintage oak timbers.

At least one tool chest held a secret surprise.

Jameel and Chris reminded everyone about safety (other than a minor chisel-to-thumb incident the week was wonderfully uneventful) and restated the strategy of the week. Monday and Tuesday were essentially team work in prepping all the stock, and the remaining time was solitary work on individual benches. My goal along with Jeff and Raney and Will, was to simply be as helpful whenever and wherever needed.

As the participants gathered in the Straitoplaner room to accomplish the first step of flattening the two faces of the timbers, the enthusiasm ran high as you might expect. I am sure that in the minds of oh, say, two dozen men in the room, the thought “I gotta get me one of these!” flitted ever so briefly in the cranium. While the machine is magnificent in its capacity for work, and surprisingly quiet at that, finding a place for a machine with the working footprint the size of a cattle trailer and probably the weight of a small dump truck presents insurmountable hurdles for a crowd of whom all work in smallish home-style workshops and studios.

Once the bench top faces were established the pieces were carted into the main workshop. Most of the bench tops were made from two pieces as required by the timbers themselves; only a handful were single slabs. But everyone pitched in, and after some fussing with the 12-inch Northfield jointer and retrofitting it with the grandest fence known to mankind, the edge dressing began.

The choreography was a delight to behold and most of the slabs required a complete team of Rouboistas to handle and feed the 150-200 pound workpieces over the jointer bed.

While this was going on Jeff and I reprised our roles as “jig makers” for the sled on the bandsaw that was used to cut the massive dovetail tenons at the end of the legs. When there are 136 dovetail tenon cuts to be made, such a commitment of time makes sense. For a single bench, it does not. The sled we made for FORP 2013 was nowhere to be found, so another version was called for. This time we made sure to mark the finished sled so it will be around for any future FORPs.

As the work on the Northfield jointer was wrapping up for the day, we got the first notion that Francis, our witty Montrealer, was dancing to a slightly different beat. He was committed to doing the maximum amount of work by hand, and the result of his hands was impressive. As he hand planed the gluing edges with his #8, the pile of full-width full-length gossamer ribbons was noted by everyone in the room.

Once the edges were ready, the gluing began. Since the water content in the wood slabs was variable the adhesive of choice was marine epoxy, a messy but effective material. Once again “teamwork” was the clarion call, as each gluing was attended to by six or eight of the crew.

Happily all the bench tops were glued up by the end of the day.

Thus endeth the first day.

We finally broke down and lit a fire last weekend as the days were still fairly pleasant but the nights getting brisk.

When working with a wood stove the emphasis for the fire is the three basics; ignition, oxygen, fuel. Matches dealt with the first issue and a dozen tons of firewood the third. Regarding the second point, the vintage hand pump bellows that came with the cabin finally ruptured the leather membrane that allows a bellows to blow, rendering the tool useless. And without a bellows to get the fire going properly first thing in the morning from the residual embers, somebody needs to get down on the floor next to the woodstove and blow. Getting down and up for that is not something I am especially adept at.

So today I carried the old bellows up to the shop, and in between working on conservation projects spent an hour stripping the old leather off and installing a new piece of deer hide I had in my stash of eccentricities. It now works perfectly, hanging in the ready next to the stove.

As for the long lasting effects of the tool, I will be able to better judge that come January or February, some morning when it is about zero degrees outside and the fire needs to get back to work. Pronto.

A fortnight ago I was en route to Barnesville, Georgia, to participate in the French Oak Roubo Project 2015. My contribution was somewhat unknown given my limitations regarding heavy lifting and moving, especially in regard to the fact that we would be fabricating and assembling classical workbenches weighing in somewhere in the 400-500 pound neighborhood. Still I was determined to contribute as best I could.

Driving through the Atlanta morass seems to be no different regardless of the time and circumstances of the effort. On this trip I was heading through at mid-day on Sunday, concurrent with a cold front moving through the area. Add water, stir, and traffic chaos results.

On my arrival at Wyatt Childs, Inc, I noted immediately (and was silently thankful that I was not a party to the activities) that the sawmill was hard at work in the driving rain, and the advance team of Jameel, Raney, John, Ted, and Chris who had joined Bo’s crew in prepping the gargantuan oak timbers was shivering. I was delighted to greet them and get inside ASAP.

There I saw the behemoth bench that Jameel’s posse built for Bo during the 2013 iteration of the event. This bench has been used hard in the intervening years, often by four craftsmen at the same time, and seems to be holding up exceedingly well.

And a new friend was there to greet me. The cat was omnipresent for most of the week following. I’m a cat guy (dogs are just too darned happy and friendly) but I find myself cat-free for the first time in approximately 55 years.

As Sunday unfolded the stack of sawn timbers kept growing until it included the rough stock for seventeen benches. While that task was wrapping up the rest of the participants began trickling in. For most of them the reaction to the location, the facility, and the materials was wide-eyed astonishment.

An afternoon-concluding highlight was firing up the grill as Chris and Narayan prepared supper for the crowd. Chris brought a cooler full of hand made Cincinnati brats and we worked mightily to make them disappear.

After the meal Jameel made a few opening remarks then turned the stage over to Chris who presented his current state of research on the lineage of the Roubo bench.

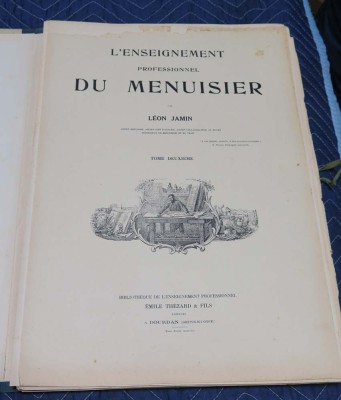

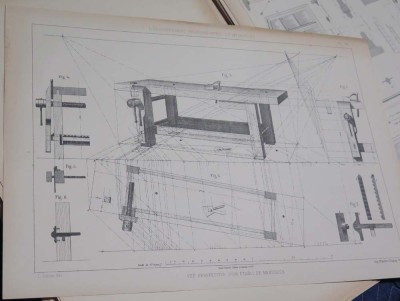

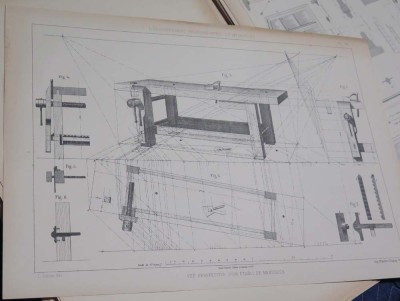

Afterward the fellowship continued as the participants acquainted themselves, I amused myself by perusing Bo’s French furnituremaking manuscripts including an eerily familiar technical drawing. Then it was off to bed for the first of several days of exhausting and exhilarating work.

I have mentioned in the past my affinity for my beefy 8×10 southern yellow pine planing beam. It is in fact the place I find myself more than any other in the shop when actually doing woodworking, especially fabrication. A recent addition to the accouterents of the work station only enhanced my gravitation to it.

Unlike many purists I feel nearly equally at home with western and eastern woodworking techniques. I am not sure if I am equally facile, but I enjoy them pretty much the same. After watching a youtube video on Japanese woodworking I came up with the “ambidextrous” bench hook, one that cne be used pushing with Western tools or pulling with Eastern tools, both right handed and left handed.

The fixture itself is a simple adaptation of the traditional bench hook/shooting board. I made two identical plates of 1/2″ baltic birch plywood and affixed them together offset by about an inch or so on either side. I then attached the top and bottom front and rear cleats as normal.

The arrangement works in the following manner (but its full utility is dependent on the fact that the planing beam is 10 inches deep): set on the beam in the “normal configuration it works as a typical right-handed push-tool bench hook/shooting board. Flipped over front-to-back it yields a second orientation that is a left-handed push-tool bench hook/shooting plane.

Starting from the original position and flipping side-to-side provides a right-handed pull-tool sawing and shooting board function, while starting from the original position and rotating it 180 degrees flat results in a left-handed pull-tool set-up.

If there is interest I will make and post a drawing of the fisture so you can make one to fit your exact needs.

Yesterday I had my final check up with the orthopedic surgeon who bolted my femur back together three months ago. He was pleased with my progress (the fracture is no longer visible in the newest x-ray; this picture is from several weeks ago) and released me to whatever level of activity I wanted to undertake. He did posit — scolding would be too strong of a word — that I was unrealistic in already abandoning my cane and I should keep it in use for several more weeks, especially when hiking the 150 yards of 15% incline to and from the shop. And, the leg strength is at about 75%, with the remaining coming in the next few weeks.

The hip has been a little cranky lately, almost certainly due to the 11-hour drive to and from southern Georgia, punctuated by a week of standing on a concrete floor during the Roubo Bench Build (more about that in coming blogs). But it felt much better today after a couple nights in my own bed and a day on the much gentler floors of The Barn.

I recently ventured upstream to check on the status on my microhydropower penstock (the pipeline) to see why it had ceased flowing. I expected to find some kind of rupture or dislocation in a planned spot following torrential rains, but I was delighted to find the line intact. What had happened was that the beta version of the new line filter, installed just before peak leaf season, had finally become encased in leaves from the stream and had clogged.

This is no small deal as the water not only flows passively into the penstock, but once the penstock is filled and the water therein pressurized, the flowing-in water and any debris it contains is literally sucked to the grill of the filter from the siphoning power of the pipeline. Given that the “siphon” contains almost 900 pounds of water falling 125 feet, that’s a lot of siphonage.

The fact that the clogging took more than three weeks during the autumn leaf deluge was extremely heartening. Literally less than two minutes of housekeeping got the system up and humming, and before I reached the bottom of the hill the turbine was cranking out electricity.

In coming weeks I will fabricate a real live “production” version of the filter which should make t a piece of cake to keep functioning. The new production version will be longer, probably three feet versus one, and may be larger than the beta’s 2-inch diameter.

Stay tuned.

Beginning round 1985 until my 2012 departure from SI I would travel once or twice a year to my home state of Minnesota to teach for and with my brother from another mother, MitchK at the Dakota County Technical College Woodfinishing Program. As much as I loved the events of the week and fellowship with Mitch and his students, I dreaded the reality that Mitch’s classroom and shop floors were concrete, and he was highly resistant to addressing the excruciating discomfort caused by my standing on concrete all day. I was wrestling with the ongoing affliction of bone spurs, which made every step feel like there was an ice pick being jammed into my heels. I guess Mitch’s years as jumping out of airplanes with full combat gear eventually numbed his feet and legs and he was unaffected by the concrete floor.

Eventually I demanded some padded mats to stand on, and that did help.

Some years later a coworker of my wife steered me to MBT shoes, which was instrumental in relieving the discomfort, and in fact probably allowed the bone spurs to disappear of their own accord. The rounded sole and heel-less configuration for MBT’s — and very high arch support — was great for walking and generally standing (the only problem was when you had to stand still with your feet at shoulder width while not holding on to anything, which would often result in losing balance when first getting used o the shoes) but they were simply not a high enough quality construction to use as work boots/shoes in the shop. They were definitely not appropriate for working the side of a rocky mountain. I’ve pretty much given up on MBT’s as a work shoe for the reason that their sole was not “grabby” enough for what I need, plus they wore out so fast. I found myself getting increasingly exasperated by a shoe that wears out in less than a year.

One option that has served me well in the shop has been Dansko’s walking oxfords, and while exceedingly well-made and very sturdy (my current pair is more than a decade old) the soles get pretty slick. Moving up and down an uneven hillside is not an option, but they are fine for the shop.

Another option that worked for me, particularly when working in the woods, was my beloved pair of Carolina lumberjack boots I bought about 12 years ago and still find them to be the most comfortable, robust boots I have ever worn. For much of the intervening period they were my “go to” boots, especially when I was traipsing up and down the mountain as their deep, knobby soles grabbed the ground and imparted great sure-footing, although they were equally comfortable in the shop. Unfortunately, they are so heavy it is like wearing a pair of cement boots. In the aftermath of getting into the ambulance for the trip to the hospital three months ago, my boots were left behind on the side of the driveway. My brother wound up bringing them into the house, and later remarked that they were the heaviest boots he had ever lifted. I do not know why they are so heavy, but they are.

After resuming my regimen of outside activities in the past few weeks, I naturally returned to wearing my old boots. I really needed the support and sure-footedness they provided, especially as my confidence on uneven ground was not what I was used to. Even so, their weight was so extreme that I could not wear them for long as my leg was still not up to full strength.

So, I needed another option.

After a ot of research I settled on a pair of knobby-soled waterproof hiking boots manufactured by Red Wing Shoes under the branding Vasque. The Red Wing brand is solid gold in the workwear world, but I wanted lightweight, hence the hiking boots. I bought a pair of Vasque boots this week and am wearing them from now on whenever I need to move around outside, and hope they work out well. So far so good, but is has only been four days thus far. Even so it has been part of the equation that has made possible a full day of hard work in the woods.

With that resolved I was motivated to finally address another issue of footing, this time in the studio. Unlike Mitch’s torture chamber my shop has wood flooring, new southern yellow pine I laid about five years ago. Much to my surprise the raw wood has become quite slick in the areas where I do most of my work. In a lot of places this is not a problem, but such was not the case in front of the planing beam. Between the slick soles of the MBT’s and the Dankso’s and the slick wood floor I could barely get anything done at the beam.

Today I solved that probel with the purchase of a large “horse mat” from the co-op. I sawed it in half lengthwise, laid it in the floor, and Presto! The problem was gone for only $30 and ten minutes.

After losing the better part of three months to forced inactivity I have been urgently addressing the heating needs for the upcoming winter with all the vigor I can muster. At first it was just an hour or two a day, but now I can manage a solid six hours of hard work at a stretch.

My last fifteen or twenty days have pretty much been the same; unless it was raining I was engaged in firewood harvesting. I’ve now managed to compile an inventory of about 10 heaping pickup truck loads. It’s about as much as we burned all of last winter, so we are somewhat sanguine about the heating situation for the cabin.

I’ll probably not be able to resume the intense processing of the firewood for a month or so until I get done with some other things. But for now we have the side shed filled, two large stacks adjacent to it left over from last winter, the side deck filled, and the front porch stuffed.

Recent Comments