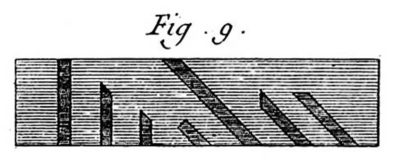

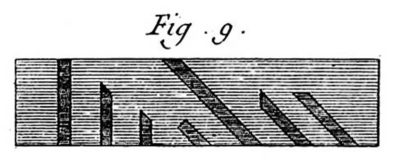

Every three or four years I teach my approach to Boullework, a branch of marquetry technically known by its original Italian title of tarsia a incastro (literally “interlocking inlay”) that was so prominent in the 17th and 18th Centuries . This identifier probably comes from the fact that all the elements of the composition — positive, negative, and sometimes additional accents — are cut simultaneously and do in fact “interlock” with each other. I always cut my marquetry vertically by free-form rather than horizontally on the chevalet, due to the fact that I have almost fifty years of muscle memory doing it the way I do it. This approach also has the advantage of allowing newcomers to begin work with only a flat board as a sawing platform, a frame saw, and some tiny saw blades, investing very little resources to begin.

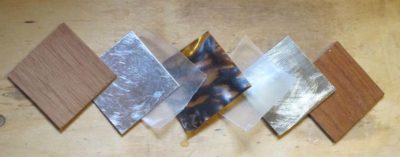

My approach also has the component of using a persuasive imitation tortoiseshell (nicknamed “tordonshell) I invented several years ago to compensate for the fact that true sea turtle shell is a proscribed material as a result of the world-wide adoption of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species adopted in 1975, essentially forbidding any commerce or other transactions involving the two species of turtle shells integral to Boullework.

That is where the three-day workshop begins, with a brief chemistry/materials science lesson on protein macro-molecules and their polymerization and the morphology of tortoiseshell.

Using materials I prepared in advance, and the addition of ingredients at the moment, the attendees begin the lengthy process of making their own to take home with them afterward (this recounting of that is condensed from work over the three days).

First they cast out a film that would become tordonshell, then created the pattern endemic to the material.

After watching me make a piece they set about to making their own. The results were gratifying.

The process took them the three days to get finished, in part because the chemistry was fighting me. In all the times I’ve made tordonshell I had not wrestled with the fundamental exothermic nature of the polymerization, but it was sure rearing its ugly head this time.

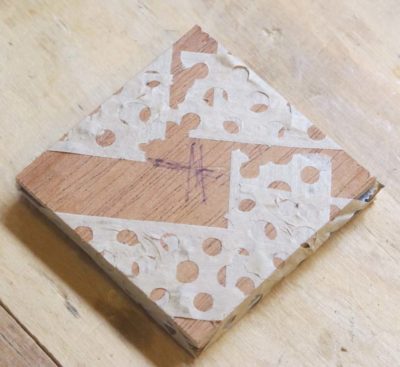

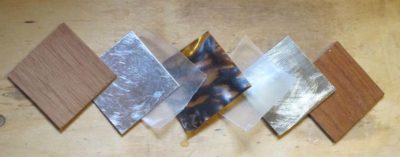

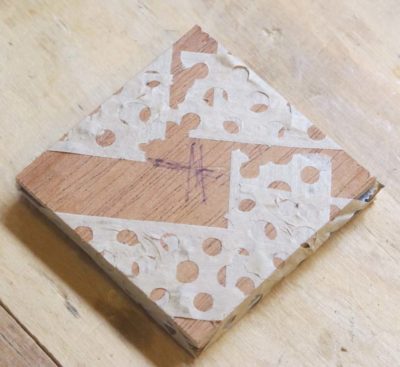

We then assembled 4″ x 4″ packets to saw (I was working alongside the attendees, I find they like me to be working on the same type project so they can peek over my should if necessary), consisting of a 1/32″ annealed brass sheet, a piece of tordonshell, and a 1/8″ plywood support. All of this was wrapped with veneer tape and the mirror-pattern of their initial was glued on to the surface with stick glue.

This approach requires beginning the sawing at the center of the composition, so a tiny hole had to be drilled with my ancient mini-eggbeater drill.

Once that was completed the saw frame was set-up and a 0000 blade was fed through the hole and the frame tightened down. this can be a frustrating task the first time, requiring four hands until you get the hang of it.. After that, no problem.

After waxing the backside of the blade the sawing (and blade breaking) began in earnest. There is a real “touch” to sawing like this, so indeed the blades were snapping right and left. Not a problem, I was expecting it. I provided the tools and blades for the most part, but John had recently purchased a new Knew Concepts saw and was giving it its first road test.

Joe had an intriguing saw from Green Lion, I only wish I’d had a chance to test drive it myself but Joe kept it busy. I think I may have to get one, just to round out my inventory. For the most part the others used Knew Concepts saws from my collection.

The sawing continued apace until Mrs. Barn called us to supper.

And that was the end of Day 1.

We recently convened our second Ripple Molding Think Tank at The Barn and great progress was made. The aggregate objectives were both vague and simple, to explore the world of making machines to fabricate ripple moldings. On an individual context I was looking to build my own version of a 17th century machine, as was Travis. Sharon wanted to start fabrication a petite version suitable for bench-top mounting and produce diminutive moldings for her own artistry.

Since last year’s confab John had already built a fully functional wave/ripple molding machine and wanted to improve its design and performance.

Starting first thing Monday morning Travis and I started cutting up some of my pile of SYP into machine structural parts, stopping to assist John in assembling his unit. By lunch time we were constructing our machine bases, both generally in tune with my First Edition Roubo prints depicting Roubo’s interpretation of a machine he had never seen.

Meanwhile John was deep into squeezing that last 10% of performance from his machine built in the aftermath of the International Ripple Molding Association first gathering. He had already nailed the ripple effect (up and down), now he was trying to dial in the wave effect (side to side).

Sharon arrived late on Day 1 just in time for dinner of Mrs. Barn’s outstanding cooking, and we were able to hit the ground running even faster on Day 2.

The first thing we did then was to record John giving us the walk through of his design ideas and manifestations.

He was effusive in extolling the outrigger arm he integrated into the cutter head, stabilizing the front-to-back flexing inherent in the cutting, and a robust drive with a drive gear and a rack mounted to the underside of the moving platen. That was an unbelievably useful exercise as we were able to get the big picture in a linear fashion as to his working and thinking about the problem, which in turn informed and directed our labors through the week.

Once everyone got back to working on their machines I began devising a system for creating the scalloped patterns that were necessary for cutting the ripple moldings. First I cut a dozen identical 8-foot strips from 1/2″ baltic birch plywood to use as the stock, then double-impregnated one edge with dilute epoxy to provide for a cleaner edge when the patterns were made.

I came up with a handy jig for making the precision patterns on the drill press.

Meanwhile machines were beginning to take shape all over the place.

The day began with the unveiling of the parquetry backgrounds glued up just before stopping yesterday. A bit of water on a sponge allowed the paper backing to be removed easily and quickly. The hot hide glue had congealed nicely but was still pretty green so we placed them in front of a fan to help dry faster.

Then it was on to trimming edges, laying out the knotwork inlay and excavating the channels for the banding.

Much of the incising as done with utility knives, but Brint in particular took a liking to my shoulder knives. He gave both of them a long test drive and had definite preferences for them. So much so that he encouraged me to have a workshop next summer to allow the participants to make one (or two). We will get together over the winter to work out any bugs for that workshop.

Meanwhile I was noodling around and found a donkey-dumb simple way to lay out the knotwork pattern with pieces of the banding itself as the measuring devices. Palm meet forehead.

For Brint and John, once the excavations were far enough along it was time to create the template block for the individual pieces of the composition.

Following the guide of Roubo they took blocks of walnut and created right-angle and 45-degree channels for the banding to be sawn and planed, then placed pieces of the banding as stop blocks in the channels. This allows for limitless production of identical elements and very fast work in creating the knotwork pattern.

And knotwork corners became manifest on the boards.

Thus endeth Day 2.

The second annual gathering of Rippleistas convenes a week from today, and I am readying the barn classroom and main room. I’ve heard back from all three of last year’s participants and they hope to be here, along with one other person who will drop by if he can. I’ve had no other confirmation of attendees wanting to join us even though the event is open-invitation and tuition-free so perhaps the charm of ripple moldings is less than I thought.

Although I no longer have the Winterthur Museum ripple molding cutter here, it having been made functional and returned, I know that one of our posse wants to experiment with a bench-top version of a ripple molding cutter, another will be perfecting his own machine built since last year, and two of us will no doubt be working on a new machine and revisiting my own machine design from last year.

I’ve ordered a pile of the nece$$ary hardware from McMa$ter-Carr so we should have everything we need to have a week of productive fellowship and undulating creativity.

Stay tuned.

Sometimes you get lemon peels, sometimes you get lemon meringue pie.

Thanks to a clearing on the calendar we’ll be convening the second Ripple Molding Soiree and Camp Out at The Barn the week of September 3. As before the agenda will be to explore the theoretical and practical aspects of making ripple moldings and their machines.

I think all of last year’s participants are coming, including at least one newly completed ripple molding machine in tow. For this year I know one of the participants is feverishly interested in making a bench top molding cutter to produce diminutive moldings and I am going to work on my prototype from last year and another Felibien-esque c.1675 model vaguely similar to the one we resurrected last year.

As before there will be no tuition fee, this is a mutual learning experience rather than a teaching/classroom event. We’ll share whatever material costs are incurred and pay for our own meals (normally for a workshop I provide or pay for the mid-day meal). If you are interested in participating feel free to drop me a line.

PS if this goes well my pal JohnH and I are hoping to teach a “Make A Ripple Molding Machine” workshop some time in 2019 and also make an instructional video on the same topic.

I was making some preparations for next month’s Boullework workshop (July 13-15) and noted that there is still space in it. If you would like to participate just drop me a note.

We’ll be making tordonshell from my own special process, and using already-cured tordonshell and brass sheet to cut a couple of tarsia a encastro designs using a jeweler’s saw and 6/0 blades!

In this technique you will cut both the pattern and the background at the same time and thus create two complete compositions, one being the negative of the other. If we add pewter to the mix it will be three compositions.

I’ll be providing all the tools and supplies for the course.

Hope to see you there.

P.S. There is also still space in the knotwork banding class August 10-12.

Acknowledging three truths, namely that 1) folks have been generally resistant to coming to The Barn for workshops (I cancelled three workshops last summer due to lack of interest but am more optimistic for this year), 2) I think I have something to offer to an interested audience based on my 45 years of experience in woodworking and furniture preservation, and 3) I am comfortable and can work very efficiently when making presentations/demonstrations without a lot of wasted time. Given these three things I’ve decided to jump into the deep end of a pool already crowded with other swimmers.

I’ve made a great many videos before with Popular Woodworking, Lost Art Press, C-SPAN, cable networks, and dozens of live interviews and such for broadcast television. I am fairly familiar with the process and recently have begun what I hope is a long-term collaboration with Chris Swecker, a gifted young videographer who has returned to the Virginia Highlands after college and some time served as a commercial videographer out in Realville, to create a number of videos ranging from 30-45 minutes to several hours. Obviously the longer videos can and probably will be cut into episodes.

In concert with this endeavor has been the ongoing rebuilding of the web site architecture to handle the demands of streaming video (and finally get The Store functional). I believe webmeister Tim is in the home stretch to get that completed.

Beginning last autumn I turned the fourth floor of the barn into a big (mostly) empty room suitable for use as a filming studio. It is cleaned up, cleaned out, and painted with some new wiring to accommodate the needs but I have no desire to make it appear anything other than what it is, the attic of a late 19th century timber frame dairy barn. It is plenty big enough for almost anything I want to do.

The only shortcoming is that the space is completely unheated and generally un-heatable, limiting somewhat our access to it. This issue came into play very much in our initial effort as our competing and complex calendars pushed the sessions back from early November into early December and the weather turned very cold during the scheduled filming. We had been hoping for temperatures in the mid-40s, which would have been just fine especially if the sun was warming the roof above us and that heat could radiate down toward us. It turned out to be cloudy and almost twenty degrees colder once the day arrived and we set up and got to work. We had to do our best to disguise the fog coming out of my mouth with every breath and I had to warm my hands frequently on a kerosene heater just to make sure they worked well so we could make the video. Yup, this will be a three-season working space for sure.

The first topic I am addressing via video is complex veneer repair. Based on my experience and observations this is a problem that flummoxes many, if not most, practitioners of the restoration arts. It was a challenge to demonstrate the techniques I use (many of which I developed or improved) in that this requires fairly exacting hand dexterity and use of hot hide glue, and the temperatures were in the 20s when were were shooting. It was brisk and oh so glamorous.

The electrons are all in the can and Chris is wrapping up the editing and post-production, so I am hoping to review the rough product in the next fortnight or so.

Paying for this undertaking remains a mystery and leap of faith. I will probably make this first video viewable for free with a “Donate” button nearby, but am still wrestling with the means to make this at least a break-even proposition. I do not necessarily need to derive substantial income from the undertaking (that would be great, however) but I cannot move forward at the pace I would like (5-10 videos a year) with it being a revenue-negative “hobby” either. I want to produce a first-class professional product, and that requires someone beside me to make it happen, and that someone has to be paid. As much as I am captivated by Maki Fushimori’s (probably) I-pad videos – I can and have watched them for hours at a time, learning immensely as I do – this is a different dynamic.

I continue to wrestle with the avenues for monetizing this just enough to pay for Chris’ time and expertise. I’ve thought about “subscriptions” to the video series but have set that aside as I have no interest in fielding daily emails from subscribers wanting to know where today’s video is. Based on my conversations with those in that particular lion’s den, subscription video is a beast that cannot be sated without working 80-100 hours a week. Maybe not even then.

Modestly priced pay-per-view downloads is another option that works for some viewers who are mature enough to comprehend the fact that nothing is free. For other viewers who have come to expect free stuff it does not work so well. I am ball-parking each complete “full-length”video at $10-ish, with individual segments within a completed video a $1. Just spitballing here, folks.

A third option is underwriting/advertising, but I find this unappealing as a consumer and thus unappealing as a provider. I have no quarrel with companies and providers who follow this path but it is not one I want for myself.

Finally there is always the direct sales of physical DVDs, which remains a viable consideration.

If none of these strategies work for me I will make videos only as often as I can scrape together enough money to pay for Chris.

At this point I have about 25 videos in mind, ranging from 30 minutes to several hours long. Our next one will require some “location” filming as I harvest some lumber up on the mountain.

Here is a potential list of topics for videos.

Making a Gragg Chair – this will no doubt be a series of several 30-45 minute episodes in the completed video as the project will take several months to complete, beginning with the harvesting of timber up on the mountain and ending with my dear friend Daniela demonstrating the creation of the gold and paint peacock feather on the center splat.

Roubo’s Workshop – L’art du Menuisier is in great part a treatise on guiding the craftsman toward creating beauty, beginning with the shop and accouterments to make it happen. I envision at least three or four threads to this undertaking, each of them with the potential of up to a dozen ~30(?) minute videos: the shop itself and its tools; individual parquetry treatments; running friezes, etc.

Making a Ripple Molding Cutter – A growing passion of mine is the creation of ripple moldings a la 17th century Netherlandish picture frames, and building the machine to make them. This topic is garnering a fair bit of interest everywhere I go and speak. I want this video (probably about two or three hours) to be compete and detailed enough in its content to allow you to literally follow along and build your own.

Building an Early 1800s Writing Desk – One of the most noteworthy pieces of public furniture is the last “original” c.1819 desk on the floor of the US Senate (home to a great many sanctimonious nitwits and unconvicted felons). All the remaining desks of this vintage have been extensively modified. This video will walk you through a step-by-step process of making one of these mahogany beauties using primarily period appropriate technology based on publicly available images and descriptions.

Oriental Lacquerwork (Without the Poison Sumac) – To me the absolute pinnacle of the finisher’s art is Oriental lacquerwork. It is created, unfortunately for me, from the refined polymer that makes poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, well, poison. Driven by my love for the art form I am creating alternative materials employed in nearly identical work techniques. Tune in to see a step-by-step demonstration what can be done.

Boullework with Mastic Tordonshell – Very early in my career I loved to carve and gild, but that passion was re-directed more than thirty years ago to the techniques of Andre-Charles Boulle and his magnificent tarsia a encastro marquetry with tortoiseshell, brass, and pewter. Once I had invented a persuasive substitute for the now-forbidden tortoiseshell, a process demonstrated in exacting detail in the video, the sky was the limit.

Metalcasting/working for the Woodworker – This is the video topic I am most “iffy” about as many/most folks will be trepidatious of working with white-hot molten metal. But I just might give it a try to show creating furniture hardware and tool-making. It’s possible/probable I might make this a series of specific projects to make the topic more consumable.

Ten Exercises for Developing Skills in Traditional Furniture Making – Based on my banquet presentation at the 2017 Colonial Williamsburg Working Wood in the 18th Century conference this series of very approachable tasks for the shop will de-mystify a lot of historic furniture making for the novice in a very non-intimidating manner.

The Compleat Polissoir – starting at the point where Creating Historic Furniture Finishes left off this would be an in-depth exploration of the ancient finisher’s tool kit and will be expanded over the Popular Woodworking video (about which I am still very pleased) with a boatload of information gleaned from my in-the-home-stretch Period Finisher’s Manual for Lost Art Press.

I’m sure there will be more ideas popping into my fertile brain, or maybe that’s fertilizer brain.

As always, you can contact me with ideas here and once we get the new web site architecture in place, through the “Comments” feature that was disabled a lifetime ago to deal with the thousands of Russian and Chinese web bots offering to enhance my body or my wardrobe.

Stay tuned.

The complete 2018 Barn workshop schedule, which I will post every couple of weeks to help folks remember the schedule.

************************************************

Historic Finishing April 26-28, $375

Making A Petite Dovetail Saw June 8-10, $400

Boullework Marquetry July 13-15, $375

Knotwork Banding Inlay August 10-12, $375

Build A Classic Workbench September 3-7, $950

contact me here if you are interested in any of these workshops.

The last session at WW18thC was my presentation of Historic Gilding and Finishing, including a brief sprint through the application of gold leaf. I described processes of gilding with a particular emphasis on building the surface (wood, gesso, bole) to make it amenable to the laying of gold leaf. It was only a few minutes, but gilding is a topic that can be introduced in either ten minutes or ten days, nothing in between makes much sense.

As quickly as I could I changed gears to get to transparent finishing, relying as always on my Six Steps To Perfect Finishing, a rubric that has served me flawlessly since I came up with it a couple dozen years ago. Not every one of the six points got the same emphasis here, that was not practicable given the time constraints, but the conceptual model was followed closely.

As always the starting point was surface preparation, including using toothing planes, scrapers, and pumice blocks that were integral to the finisher’s tool kit 250 years ago.

The final step in surface prep was to burnish the wood with polishing sticks or fiber bundle polissoirs.

I then moved into the no-man’s-land of filling the grain and building the foundation for the finish yet to come, employing the traditional method of using beeswax as the grain filler. In some circumstances this is the finished surface, in others it is the foundation.

In olden times they would have used a fire-heated iron to melt on the beeswax, I use a similar shaped tool that is electric. The molten wax is drizzled on to the surface then distributed with the heated iron unto there is excess. After cooling any excess is scraped off.

When choosing the finish itself, an 18th century palette would have been based on four major families of finishes. From left to right they are shellac, linseed oil, beeswax, and colophony (pine rosin).

In this demo I used padded spirit varnish (shellac) to show the application of the finish over the beeswax grain filling.

And then my time was up and everyone went home.

****************************************

I’ll be offering my annual Historic Finishing workshop at the barn in late April. Let me know if you would like to participate.

Since seeing my first piece of antique furniture decorated with tarsia a incastro, or “Boulle work,” I have been captivated by both the art form and the technique.

This ancient method of using a minuscule blade in a frame saw, usually a jeweler’s saw in our time, for cutting patterns in two or three layers of material comprised of the shell of a sea turtle, a sheet of brass, and sometimes a sheet of pewter, remains captivating to this day. The result is the same number of completed compositions as the original number of layers in the stack.

Due to the prohibition of trade in turtle shells I invented my own very convincing replacement material I call Tordonshell.

So these three days will comprise of making your own piece of Tordonshell (I will have some pieces made in advance for the workshop) and sawing patterns from packets we will assemble for cutting.

Though we will be cutting them vertically to begin, there is a chevalet in the classroom and anyone who wants to give it try is welcome to do so.

*********************************************************

The complete 2018 Barn workshop schedule:

Historic Finishing April 26-28, $375

Making A Petite Dovetail Saw June 8-10, $400

Boullework Marquetry July 13-15, $375

Knotwork Banding Inlay August 10-12, $375

Build A Classic Workbench September 3-7, $950

Recent Comments